Featured in

- Published 20131203

- ISBN: 9781922079992

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

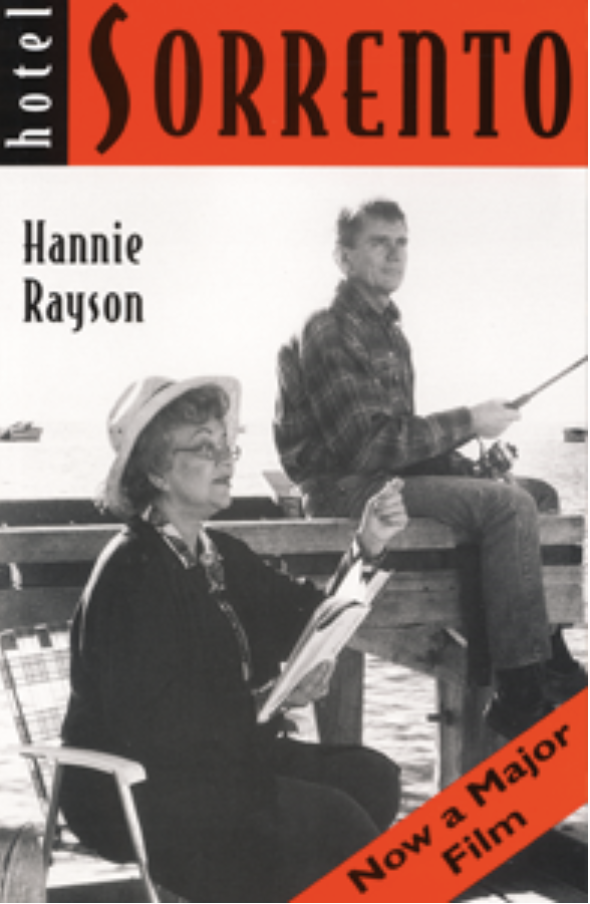

On ‘Hotel Sorrento’, by Hannie Rayson

GR Online HANNIE RAYSON'S WELL-loved Hotel Sorrento, which premiered onstage in 1991 and was made into a feature film in 1995, explored some immediately identifiable terrain...

More from this edition

The ghost river

FictionWhen he was about to begin the river story Moses would stamp at the ground with the heel of his boot and call out to the birds in the trees, 'listen hard now'. He'd clap his hands together a couple of times, make a clicking noise with his tongue and the birds would lift off from the trees in the distance and move a little closer, to the wattles lining the riverbank. 'Back in the old time, before the humans,' he would begin, 'this girl, the river, she didn't stop her life where she does now, at the mouth at bay there. There is no bay in the time I'm talking with.'

Three bunyips

MemoirMY FIRST ENCOUNTER with a bunyip was in a School Paper, the monthly supplement to the Victorian School Readers: Eighth Book (HJ Green, Government...

Interview with

Cecilia Condon

InterviewCecilia Condon is a Melbourne based writer and actor. She works at the Wheeler Centre for The Emerging Writers' Festival and you can find...