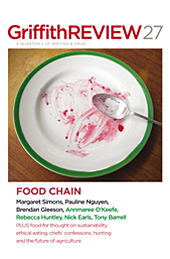

Featured in

- Published 20100302

- ISBN: 9781921520860

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

‘WHO CARES? I mean, who the fuck cares?’ This is more exclamation than question. Patrice Newell is exhausted. Exhausted and angry. Angry at ineffectual government, at obtrusive bureaucracy, at ignorant consumers, at naive environmentalists, at greedy industrialists. Possibly at me. I’ve rung to discuss visiting her farm, Elmswood, and have caught her at a bad moment.

She has just finished a ‘spectacularly difficult’ garlic harvest. November brought the Hunter Valley six consecutive days of temperatures higher than 43 degrees, the bulbs over-heated, and there has been a marathon packing of four hundred boxes. The intense physical labour of all farming, but particularly organic farming which replaces pesticides with human toil, is something of which most Australians are ignorant. ‘People say, “Oh, you’ve kept your figure,” and I say, “Do you know fucking why?”‘

Garlic is Patrice’s new focus. Bought direct from her website it retails at $38 per kilogram. Chinese garlic, which holds 90 per cent of the market in Australia, sells for around $2 a kilo. This is a price differential she acknowledges as insane. ‘People ask why it is so expensive and I just say, “Are you kidding me?!” I don’t know any farmer who is making any money, so don’t you dare bitch about the price of food!’

It is the week before Christmas, the temperature has climbed back up into the 40s, sleep is impossible and Australia Post is threatening strikes which will wreak further havoc with the garlic orders.

A month later when I am seated in Patrice’s cheerfully overflowing kitchen, the view – across a cascading crepe myrtle and a scattering of Balinese temple gods and Spanish pots collected by her partner, Phillip Adams – is of the surrounding hills, a staggering ten thousand acres of which belong to her. As she cooks up an omelette with eggs from their chooks and herbs from their biodynamic garden, this seems to us city visitors the pastoral made real.

It is beautiful, certainly, but no idyll. Patrice has written three lyrical and instructive books about life at Elmswood[1], but there is a telling omission from her most recent, Ten Thousand Acres: A Love Story. She had planned to include a section on the business realities of farming but was unable to find the right tone. She and her editor eventually agreed that talk of figures and futures could not be made to fit, and the section was scrapped.

Finding the right tone for our discussion of farming is what we are struggling with as a society. There is a cultural dissonance between the lingering urban idolatry of the cocky, the bushy in the Akubra, and our insistence on cheap food at the expense of environmental devastation and farm failure. In his 2001 Boyer Lectures, Geoffrey Blainey commented, ‘My view is that the rift between country and city is wider than at any time in the last one hundred and fifty years.’[2] And nowhere is that rift wider than between the way the city wants to eat and what that does to the country.

Farming has always held more than financial value in Australia. For the first Europeans, the transformation of empty wilderness to fertile farmland was a moral and religious duty, as much as an economic benefit. It was also considered key to the improvement of convict character. The wool pioneer John Macarthur lobbied colonial commissioner JT Bigge on the redemptive benefit of farm work: ‘I am confirmed in the opinion, that the labours which are connected with tillage of the earth and the rearing and care of sheep and cattle, are best calculated to lead to the correction of their [the convicts] vicious habits – when men are engaged in rural occupations their days are chiefly spent in solitude – they have much time for reflection and self-examination, and they are less tempted to the preparation of crimes than would herded together in towns, a mass of disorders and vices.’[3]

The tree change phenomenon is a contemporary echo of those earliest assertions of the moral superiority of rural life to the unwholesomeness of city living. People want to escape the city, to find meaning through life in the country. Patrice Newell’s books describe exchanging an urban world, which centres on being seen, for a life based on careful, exact and reflective looking. In Ten Thousand Acres, she quotes Phillip saying, ‘The farm’s been good for you.’ Adding, ‘Certainly it has kept other worlds at a distance; it can obliterate their sound and fury. And it makes me conscious of my limitations.’ But while most modern tree changers do not intend to make a serious income from their rural land, Patrice always did. It was this determination that shocked and amused her city friends back in 1987. They could well understand the appeal of a country weekender but not of a serious, working farm.

The family farm was the site of our nation’s earliest dreams of prosperity and social equity. The issue that dominated the first colonial parliaments was land reform, and in the 1850s thousands joined the campaign to wrest the fertile land of south-eastern Australia from the hold of established pastoralists. The resulting Selection Acts were intended to create a society of self-sufficient producers, though in practice they served more to entrench the wealth and power of the squatters. Nevertheless, successive governments promoted the creation of a large number of small holdings run by independent farmers. While the rhetoric remains to this day, policies intended to encourage the ideal of the yeoman farmer have been in decline since the 1970s when global trade began to triumph over national schemes of price fixing and controlled production.[4]

The economic health of the family farm, and of the country towns these farms depend upon and support, are now trapped in a downward spiral. This is the conclusion drawn by social researcher Neil Barr in his recent book, The House on the Hill: The Transformation of Australia’s Farming Communities[5]. Barr’s family began farming in Australia in the 1850s. He grew up on a small, struggling stone-fruit orchard outside of Melbourne, and has spent thirty years ‘pondering over the joy, despair, and paradoxes of farming life’.

Barr’s analysis is considered, clearly argued and quietly catastrophic. His starting point is the stark fact of declining commodity prices. He uses his parents’ experience as an illustration: when they bought a farm in 1953, ten acres of productive orchard was sufficient to earn a reasonable family living. The falling price of fruit joined with the rising cost of growing it meant that before too long the amount of land required to make an income rose to fifteen acres. It kept rising. Barr’s parents gave up when it reached thirty.

The same unhappy coupling of falling product prices and rising production costs applies to sheep, wheat, dairy farms and most other agricultural pursuits. The declining price of agricultural products is the main reason why agriculture’s share of our economy is now 4 per cent, down from 14 per cent in the 1960s[6]. ‘Get big or get out’ became a truism of modern farming: if farmers survive it is by buying out their failing neighbours. Only one in two farming families will pass the business on to a successor within the family[7]. Agricultural economists argue that farm dynasty failures are necessary for overall market sustainability; what we need, in fact, is for many more farmers to leave their land[8].

Barr’s analysis untangles the net of social developments which are contributing to the transformation of rural Australia. As significant as international trade laws is the domestic revolution that has taken women away from the kitchen and into paid work, and the resulting impact this has had on our relationship to food. Time spent preparing the evening meal, for example, has dropped from two hours in the 1950s to one hour in the 1980s, to between twenty and thirty minutes today[9]. Combined with shrinking households and the loss of culinary skills, the result is a rising demand for supermarket convenience food and fast food. With shoppers increasingly turning away from raw produce to processed food like frozen chips and tinned tomato sauce, farmers are getting an ever smaller proportion of the money we spend on food.

The farmer’s financial position is further weakened by the places we like to shop: supermarkets. Seventy-five per cent of domestic vegetable purchases are now made in supermarkets, overwhelmingly in the two big chains, Coles and Woolworths[10]. Supermarkets have established direct contractual supply arrangements with producers, bypassing the old wholesale fruit and vegetable markets and livestock saleyards. It is in the economic interest of supermarkets, as it is for the food processing industry, to deal with as few suppliers as possible. Rapid consolidation, in the parlance of economics, is the result. Get big or get out, all over again.

Supermarkets further reduce their costs by transferring risks, such as that of quality control, to suppliers. In January 2010 the Sydney Morning Herald ran a front page story revealing that each year a million tonnes of Queensland bananas, a third of the crop, is rejected by Coles and Woolworths for not meeting exacting product specifications, which stipulate acceptable length, girth and colour. Woolworths’ spokesman Benedict Brook pointed the finger at the consumer: ‘The fact is customers, given the choice between fruit that is bruised and fruit that looks pristine, will choose the [the pristine fruit].’[11]

Add to this mix investors cashed up from the mineral boom and the compulsory superannuation contributions of an ageing population. This has fuelled the remarkable growth of Managed Investment Schemes which seized upon the tax attractiveness of investing in large agricultural businesses. Capital invested in horticultural Managed Investment Schemes quadrupled between 2000 and 2005[12]. This means traditional family farms are now in direct competition with the corporate sector for land and water.

In these MIS farms the model of family ownership is replaced by a network of distinct investors: some owning a share of the income from the farm produce, others the farm’s land and water, and still others invested in its management and marketing. The only landscapes these investors see are the troughs and peaks of their annual statement.

Barr concludes, ‘there is only one type of farm business that will survive in the mainstream food supply chain.’[13] That is, the large, extremely efficient, technology-driven corporate farm.

Where does that leave small-scale farmers who cannot, or do not want, to expand? One choice has been to move into boutique agricultural products, ranging from alpacas to organic figs, to ostriches. But Barr is cautionary about the long-term financial viability of this response. There are limited opportunities for producers outside the supermarket-dominated integrated food supply chains, with the rise of alternatives such as farmers’ markets seen as a niche option only. Where signs of significant success do appear, supermarkets move in. Witness the explosion of organic food. In the United States, the biggest retailer of organic groceries is now Wal-Mart[14].

Another option, put plainly, is to give up.

CRESTING THE BEND on the road from Gundy to Elmswood, the landscape of golden paddocks and grey gums is pierced by a giant bronze statue of Mercury, poised on one leg, right arm aloft. At first sight, this monument at the property’s entrance heralds the well-known classical tastes of Phillip Adams. But the choice of the Roman god of trade and commerce as Elmswood’s sentinel, in truth, more befits Patrice, who for twenty-five years has wrestled with the hard economics of modern farming, seeking to marry her love for the landscape with the need to make a quid.

Elmswood might seem an anomalous family farm – owned by a former TV journalist and model, and one of the nation’s best-known broadcasters and columnists, with a stash of Etruscan pottery in the lounge room, and lunch guests who can include Tim Flannery or Christopher Hitchens – but the situation at Elmswood exemplifies much of Neil Barr’s argument about the state of Australian farming.

Most obvious is the financial squeeze of falling food prices and rising farming costs, coupled with the boom-bust cycle of many boutique agricultural crops. Patrice’s first book, The Olive Grove, describes the beginning of Elmswood’s adventure in olive growing. As with all farm stories, catastrophe is a leitmotif (while Karen Blixen’s coffee plants burned, Patrice’s olive trees froze), but her passion for the product and long-term commitment are never in doubt. The success the book anticipates, however, has not been forthcoming.

Barr specifically cautions against ‘the dream’ of olives: ‘Olive oil is a bulk commodity traded in large volumes in world markets. The advantages of scale apply to olives just as they do to wheat.’[15] Patrice acknowledges, ‘It would be true to say that all the financial projections that we did back in the ’90s were wrong, across the board.’ The quality of the oil she makes is very good, but the volume of production has been restricted by the Hunter’s climate, particularly by the farm’s dependence on tank and river water during a period of extended drought. Her six thousand trees, she knows, count as ‘nothing’.

But, it turns out, size and corporate structure do not guarantee success. Established in 1999, Olivecorp, with more than six thousand hectares of olive groves spreading out from the little Victorian town of Boort in the Murray-Darling Basin, had been the very model of a new Managed Investment Scheme agribusiness. But last year its parent company, Timbercorp, put itself into voluntary administration, undone by the financial downturn and the government’s reassessment of MIS tax breaks.

At least Patrice’s trees pay for themselves. She is, however, operating under the same market forces. ‘In the end, you just have to accept that if the market – and this is the truth of it – that if not enough people want to buy the product, then I will have to face the reality of pulling the olive trees out. Let sheep eat them out – I don’t know. That’s just the reality of it.’

She is now ‘obsessed’ by growing garlic, loving the produce and revelling in the immediacy of its annual cycle, in contrast to the slow and expensive process of raising beef, which remains Elmswood’s biggest money-spinner. But in focusing on garlic, Patrice may be heading for even more heartache than olives brought her. The horticultural industry faces particular threat from overseas competitors who offer ever-lower prices through poor safety and environmental standards and cheap labour. Like so much else in our future, China is looking like the significant player in this story.

China is maintaining an unpredicted level of food self-sufficiency (except, apparently, cheese for pizza toppings[16]). It is now redirecting its agricultural efforts towards export markets, in the past decade quadrupling the area devoted to fruit and vegetable production.[17] At the same time, the demand for cheap groceries is increasingly turning Australians to foreign-grown produce. In 2007-08 horticultural imports exceeded exports for the first time ($1.5 billion opposed to $1.33 billion), with imported goods now exceeding 20 per cent of our total fruit and vegetable intake[18]. Five years ago there were more than 4,000 vegetable producers in Australia. The agribusiness consultant David McKinna has predicted that number will soon drop to less than a thousand[19].

Patrice Newell also faces the challenge of reaching consumers outside the supermarket aisles. Farmers’ markets are a good model, she says, but one with a limited application. They suit small-scale farmers who live close to urban centres. But for those trying to make a real living off their land, and meet the spiralling expenses of employing staff and running machinery, five hours of selling on a Saturday is simply not sufficient. Plus, selling is not farming.

‘And this gets back to the heart of my anxiety,’ says Patrice. ‘If you make a commitment to becoming a primary producer it’s because you’re actually interested in the primary production.’ But farmers’ markets and other strategies of ‘income consolidation’, as the agriculture bureaucrats term it, ‘invariably involve stepping outside of primary production and getting into some form of marketing. And if you meet the really clever farmers, they’re not marketing people, they’re primary producer people! But we live in a society where there is no huge honour in being a primary producer.’

Patrice’s saviour has been the internet. It allows her to sell direct to consumers without having to leave the farm. But it still demands precious time and energy. ‘It means I have become a primary producer who at the height of the garlic season, a hundred per cent of my effort is not in primary production.’ With her public profile and eagerness to interact with buyers, many of whom are as passionate about the product as she is, Patrice hardly fits the stereotype of the taciturn bushman. Yet when she says, ‘I’ve done something that I swore I would never do…I’ve become a retailer,’ it is as though she is revealing a dirty secret.

Neil Barr concludes that the best strategy for small-scale producers to remain on the farm is for the farmer or their partner to find off-farm work. There is an old joke that a viable farmer is one married to a nurse or teacher, and the point holds for Elmswood, even if in this case it is a national radio personality who is keeping things afloat. Where Patrice and Phillip really buck the trend is that it is the man taking employment off the farm, rather than the woman.

Like many farmers, Patrice’s aim is to leave the farm in good financial state, fully systematised and productive, so that her daughter has a real choice about whether to continue with it or not. Patrice is no ‘back to nature’ modern primitive. She is in favour of change, supports growth. Her unsuccessful foray into electoral politics with the Climate Change Coalition was based around building alliances with the business community rather than existing green parties. Patrice is neither naive nor a romantic. And she is convinced that it is not her sums which are full of holes.

WHEN WE MEET at Elmswood, Patrice’s manner is in a whole other key to that first phone conversation. She and Phillip have enjoyed time alone at home together, taking a break after the garlic harvest. The season was a success, with every box sold and the delivery glitches finally sorted out. And there has been rain. Across the country it was a wet Christmas and New Year, and on her property the hills are a long-since-seen soft green, with water in the creeks.

Patrice’s passion for farming, and her frustration, is still present. As is her sharp intelligence. But on her home turf I also experience Patrice’s generosity and hospitality. She is a woman with a strong voice and a serious, attentive gaze but her laugh is unexpected, high and girlish. Her relationship with Phillip is warmly affectionate, and as she and I talk he good-naturedly harrumphs about, patting the dogs, looking for lost keys, wanting lunch. The contrasts between the two are so marked that difference must be an ingredient in their happiness. While Patrice advises on the benefits of crosswords for staving off dementia and muses about moving to chilly Tasmania to encourage physical activity while ageing, Phillip delightedly unwraps a chocolate bar for breakfast.

Sipping on green tea, Patrice is unimpressed by my synopsis of Barr’s research. Farm aggregation and corporatisation is an old story, she says, but what is still being ignored is ‘the ecological consequences of the trajectory that we are on’. It is those consequences that are at the heart of our nation’s future, she asserts, not just its farms.

The environmental consequences of Australian agriculture are well known, but remain shocking. Around 70 per cent of the five hundred million hectares of land used for agriculture in this country is degraded[20]. In such a context, there is little sense in considering agricultural success solely in terms of financial profit.

According to Patrice, the fundamental problem is that most of us – farmers, investors and politicians alike – still fail to accept that land has limits. In one reading, the story of Australian agriculture has been a triumphant tale of remarkable gains in productivity. The year of Federation – blighted by drought, falling commodity prices and the financial collapse of irrigation co-operatives – was dire, but then the ascent began. Wheat yields started to rise in 1902 and have continued to do so ever since. This is increasingly true for Australian farming as a whole, with farmers here producing twice as much in 2005 as they did in the 1970s[21]. But this constant increase in productivity has come at the price of environmental degradation. The steps taken by farmers to develop land in this country – clearing, poisoning native grasses, draining swamps, intensively fertilising – created the current environmental crisis.

‘You need someone to be bold, to make a commitment and say the nasty, which is: that’s the limit,’ Patrice contends. She calls industrial agriculture’s promise that changed input (a genetically modified crop here, more chemical fertiliser there) can produce endless economic gain ‘the great lie’. ‘The fact is the earth does have a limited capacity.’ For this reason, Patrice argues, a lot of small farmers, ideally organic and biodynamic, spread across the land will always be smarter environmentally than a few big farms. ‘When you really learn about farming you understand the capacity of land. This is an important part of an organic farmers’ knowledge, because we’re always trying to make judgements about maximising profitability while never compromising the land.’ A network of small farms also minimises weather risk and reduces distribution distance.

She is indignant when hearing politicians discuss the Murray-Darling crisis as though it were about water. ‘Industrial agriculture people, public companies with shareholders to look after, are completely focused on growth. They don’t want to have a reduction in the agriculture of the Murray-Darling Basin. But if you continue having this appalling agricultural activity, on this level, you’re not going to fix the Murray-Darling. The Murray-Darling Basin is a land management problem, not a water issue.’

Patrice acknowledges that small farms are not necessarily good farms. But there is no escaping the time and effort required to gain proper knowledge of the land for which you are responsible. When she started at Elmswood, old farmers walked her around the property explaining which hill was a good spot for the young heifers in winter, what happens when the streams flood. Growing things requires a huge amount of observation, she repeats. To treat rural land as real estate which can be managed by discrete groups of absent shareholders all chasing the highest profit is a recipe for environmental disaster.

Early on in Patrice’s farming career she embraced biodynamics. Biodynamic farming focuses on soil health, seeking to actively enrich soil through non-artificial fertilisers, particularly a preparation known as 500 which consists primarily of long-stewed cow manure. In contrast to a certain strain of environmentalism, Patrice believes there is a valid place for grazing in Australia, so long as animals are managed appropriately. She laughs remembering a conversation with a group of entomologists at the Australian Museum, all of whom were mortified at the revelation that she grew olives, kept bees and ran cattle. Their solution to the environmental challenges of Australian agriculture? Farm macadamia nuts.

Despite the Christmas rains, drought in New South Wales has spread, with more than 95 per cent of the state fully or marginally in drought at the beginning of the new decade. Late in 2009 Kristina Keneally made her first trip as state premier to the state’s drought-affected northern and western districts, announcing an $8 million package to extend assistance measures. Patrice is disparaging. ‘She flew over the country, and most of NSW is practically without grass cover. Now if the agricultural sector of New South Wales was tuned into the environmental consequences of farming, that would never have been allowed to happen. How do you know you’ve made progress? You’ve made progress when no farmer in their right mind would dare let their land become bare earth. When the community wouldn’t allow it!’

On a recent drive through Melbourne’s outskirts she was incredulous to see sheep crowded into dirt paddocks. ‘Why isn’t every neighbour up in arms? Why aren’t they saying, “This is completely unacceptable. You are a disgrace!”‘ She argues there needs to be a cultural shift, of the kind that happened with domestic violence and workplace safety, so that land management of this type is simply no longer considered permissible.

To encourage that, government should only be aiding those who ‘are on a trajectory of a more sustainable, more environmentally conscientious farming, in an area that can sustain a long-term agricultural position.’ Patrice appreciates first-hand the failures of narrowly prescriptive environmental legislation, saying that good land management is not about restrictions but responsiveness to each landscape’s individual needs and capacities. But she does not believe the environment has yet achieved its proper political status in this country.

Musing on the consequences of Bob Hawke’s creation of the environmental portfolio back in 1983, Patrice wonders if this has effectively sidelined environmental considerations from political decision-making. A Minister for the Environment maintains the fiction that soil, air, water are something separate, out there, and that we can choose whether to engage with them or not. ‘If I were really a serious and bold leader one of the first things I’d do would be to get rid of the environment portfolio.’

Patrice is hardly a lone voice when it comes to declaring that Australian agriculture needs a fundamental shift in its environmental attitude. The former chief of CSIRO Land and Water, John Williams, a long-term advocate for sustainable agriculture, has put it bluntly in official reports: ‘business as usual is not an option.’[22] But, as another environmental scientist said to me, it is hard to be green when you are in the red.

And a central issue here is our appetite for cheap food. We consumers have been taking economic advantage of the revolution in food supply, with Australian expenditure on food now 14 per cent of household income, down from 22 per cent in the 1960s[23]. Patrice is adamant that falling commodity prices are a furphy. Food has never been costed properly, she argues, as prices fail to factor in environmental expenses. Australia’s industrial agribusinesses do not pay for their real water use or soil degradation: the big profits are a mirage.

She returns, fiercely, to the pledge Kevin Rudd made throughout the 2007 election campaign to address what he termed ‘inflated grocery prices’[24]. ‘One of the biggest problem we’ve got is Kevin Rudd, because if you run a campaign saying “I’m going to keep food prices low” to get elected, then he clearly does not understand the reality. What leaders say helps define an attitude. And if he continues to say that he is not grasping the truth of the circumstances.’

‘People don’t realise that they do pay for their food in different ways. Take the Murray-Darling. If industrial agriculture hadn’t damaged the Murray-Darling Basin, John Howard wouldn’t have allocated twenty billion to repair it. That is a cost we’re all paying. For some reason we can accept it, or politicians can sell it, because it is a repair bill for a national icon. But if we were to pay a higher price for food that prevented damage, all we hear about is ‘the price of food is too high!”

Weaning us off our dependence on cheap supermarket produce will not be easy, and is hardly an alluring task for any politician. But Patrice maintains hope. ‘Trajectories happen because we don’t change them! If we want to change them we can. Do we want to change? That is the question…See, what’s the most important thing? Is the most important thing cheap prices, or is the most important thing maintaining the integrity of the environment of Australia, for the people of Australia?’

For an industry that currently exports 70 per cent of its product (for some crops, such as wheat, the figure is more like 80 per cent), Patrice accepts that any changes to the way food is costed will have massive economic impacts. But she insists that this dependence on exports is what we should be giving up, rather than small, independent, environmentally sustainable farms. ‘What’s the point of destroying the Murray-Darling Basin to export food? I mean, why?’

A LOT HINGES on what we put in our mouths; our farmers and our environment are only the beginning. There are issues of food security as our imports of food increase; ditto, food safety; rising levels of obesity and chronic disease; even the prospect of compromised national security with the collapse of so many country towns. There is also the question of how we see ourselves as a nation.

Despite his personal connection to the tradition of family farming, Neil Barr is phlegmatic about its end. ‘Of course, there is little real hope of passing on the farm to the next generation as a viable business. Once this is realised and accepted, then much of the pressure on older farmers to chase the declining terms of trade with increased productivity is eased.’[25] I know one elderly dairy farmer, stoic as a statue, who wept when his middle-aged son finally raised the subject of the family needing him to earn some money off the farm.

As a society we are still receptive to these stories of individual heartbreak. But for how much longer? Barr speculates that as fewer and fewer Australians have direct knowledge of farming it will inevitably decline in our national consciousness and the long emotional connection, already sentimentalised, will wither. Will family farms become a picturesque but impractical memento from our national past, like neck-to-knee bathers and the outdoor dunny?

For Patrice Newell this would be a tragedy, personal and national. ‘When I came here I wanted to be remunerated and celebrated. I wanted people to believe what I was doing was good.’ Those of us living in cities, chowing down on cheap imported groceries, may not care if she has achieved only half of that equation. But there is no opt-out clause for thinking about the way we farm in this country. ‘There’s the saying, you know, if you eat, you’re involved.’

[1] Newell, P. (2006). Ten Thousand Acres: A Love Story. Camberwell: Lantern.

—. (2003). The River. Camberwell: Penguin.

—. (2000). The Olive Grove. Camberwell: Penguin.

[2] Blainey, G. (2001). This Land is All Horizons: Australian Fears and Visions. Sydney: ABC Books, p.32.

[3] Macarthur quoted in Hoorn, J. (2007). Australian Pastoral. The Making of a White Landscape. Perth: Fremantle Press, p.53.

[4] Macintyre, S. (2009). A Concise History of Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.97-99.

[5] Barr, N. (2009). The House on the Hill: The Transformation of Australia’s Farming Communities. Canberra: Land & Water Australia in association with Halstead Press.

[6] Barr, p.8.

[7] Barr, p 11.

[8] Barr, p 30.

[9] Barr, p.81.

[10] Barr, pp.85-86.

[11] Brook quoted in Marriner, C. (2010). ‘What’s being dumped because it’s not this long?.’ The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 Jan, p.1.

[12] Barr, p.90.

[13] Barr, p.90.

[14] Paumgarten, N. (2010). ‘Food Fighter: Does Whole Foods C.E.O know what’s best for you?’ The New Yorker. 4 Jan., p.47.

[15] Barr, pp.59-60.

[16] Barr, p.18.

[17] Barr, p 19.

[18] Austin, N. (2009). ‘Australia imports more fruit and veg.’ The Advertiser. Retrieved January 12, 2010, http://www.news.com.au/adelaidenow/story/0,22606,25400856-2682,00.html

[19] McKinna quoted in Barr, p.87.

[20] Myers, P. (2009). ‘Push for maverick techniques to restore landscape.’ The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 15, 2010,

http://www.smh.com.au/national/push-for-maverick-techniques-to-restore-landscape-20090911-fkqi.html

[21] Barr, p.6.

[22] Williams, J. (2001).‘Farming Without Harming in an Old, Flat, Salty Landscape.’ Retrieved January 15, 2010, http://www.clw.csiro.au/staff/WilliamsJ/qld-paper_july01.pdf

[23] Barr, p. 7.

[24] ABC News. (2007) ‘Parties lock horns on grocery prices.’ Retrieved January 13, 2010,

http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/07/11/1975589.htm

[25] Barr, p.58.

Share article

More from author

In the waiting room

ReportageTANYA SITS AT the side of the couch, her head resting on her hand. She smiles when I say "hello", but her two-year old...

More from this edition

Food security in the Arctic

EssayIN 1847, FOUR years after being stood down as lieutenant governor of Tasmania, Sir John Franklin died at the other end of the earth...

Farming for a hungry world

GR OnlineIS AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE ignoring organic-style farming?Southeastern Australia has been gripped by one of the worst drought on record, yet Tim O'Halloran is a remarkable...

Shopping for revolution

GR OnlineI'TS A MUNDANE household task: peel the shopping list off the fridge and take it to the shops. But if, like me, you were...