Featured in

- Published 20170207

- ISBN: 9781925498295

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Then the Grinch thought of something he hadn’t before! Maybe Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store.

Dr Seuss, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

MAT DRIVES AND I peek at the speedometer, feeling a grip of tension in my stomach as we curve through the roads to Brukunga. I haven’t memorised the drive yet, even though we’ve been together for three years and visit his family regularly. Even if I could drive to Brukunga, in the Adelaide Hills, without the help of a GPS, I’d be too nervous. Mat once told me that when he was seventeen, he came across a car accident on a country road. A car had spun out and collided with a tree. The driver’s head hit the steering wheel and he’d died instantly.

‘Babe, pull over,’ I mutter between gripped teeth, ‘I’m gonna be sick.’

He veers my dad’s battered silver Honda onto the side of the road, and I crawl out and start to wretch. The dirt is coarse on my hands and knees, and the sun shines on my neck as I spit bile and drool.

Mat’s parents are the last stop on our Christmas schedule. When we arrive, as always, I jump out of the car and open the farm gate. The property is small, thirty acres, with around eighty alpacas, thirty or so sheep, a handful of miniature goats, a litter of kittens, a growing number of ducks and chickens, and a small pack of kelpies. We used to bring our greyhound, Suzie, out to the farm. She would roll in the hay, spreading shit and grass all over herself. We stopped after she caught a chicken and stunned the poor thing so badly that it didn’t recover for hours. Now it’s just us, along with Mat’s two brothers and their partners, and the neighbours.

Christmas in Brukunga comes with the traditional fayre: roast lamb with potatoes, salad and champagne. It’s 5 pm and we sit outside on spongy chairs. When the conversation falls away, we listen to the galahs cavorting and the alpacas bleating. The dogs linger under our feet, waiting for us to toss them a greasy potato or piece of bone.

‘Are you eating meat this year?’ Mat’s mum asks.

Mat replies, the same as always, ‘Still a vegetarian.’

I fiddle quietly with my fingers and avoid thinking about another meal. We’ve been eating all day and there isn’t much room left to breathe, let alone eat.

We play poker and the game finishes late, with Mat playing his older brother. The silence settles as they look over their cards, and I remember Mat’s frustration when his brother spoke about people on Newstart earlier in the night. The tension grows as I sit and wait, a bowl in front of me, sticky with melted ice-cream. I lost all of my chips early, betting everything away on a hand that turned out to be nothing.

WHEN I TURNED nine, I realised the Christmas holidays weren’t for me. I didn’t care for the crowds and the rush. I despised the carols. I hated how the tree would linger until late January and how I would have to wrestle ornaments from my dog’s mouth. Rehanging these drool-covered baubles was about as much fun as playing charades with my dad’s side of the family.

I loved making pudding every year with Dad; it was the only time we would cook together. But I felt uncomfortable crowding around the pudding for photos on Christmas day. The blue flames, rich with orange tips, would rush around the pudding as everyone cheered and I slunk behind Dad’s legs.

My best memories of Christmas were being at my yiayia’s house eating crayfish, sprinkled with lemon. We only ate crayfish at Christmas; it was too expensive for any other time of the year. And besides, the two became synonymous, so it would have felt wrong to eat crayfish at any other time.

I would sit at the table, napkin tucked into my T-shirt. My yiayia barely sat down to eat; she would spend the meal rushing back and forth from the kitchen to the table, making sure everything was perfect. My uncle, who always had car oil embedded in the creases of his thick fingers, would show me how to break the crayfish shell and wrestle out the meat. My yiayia would spend the early hours of Christmas morning shelling the prawns that my uncle bought fresh from the market. They were always shelled perfectly. I imagined all of the hours of work her nimble hands had done just for us.

MY UNCLE’S FAMILY live in Redwood Park, above Paradise and forty minutes north of the Adelaide CBD. The land is paved and sparse, woven with four-lane roads and dust. I go there for Christmas lunch every two years, alternating with my parents’ house. That means every second year, Mat and I drive 25.5 kilometres from home to Redwood Park, forty six kilometres from Redwood Park to Brukunga, and then fort-four kilometres home.

Christmas, for Mat and I, is spent almost as much inside a car as outside. As we travel through the state, we take deep breaths in these pauses. Exhaling the baubles, noise and laughter. We listen to the radio occasionally, but most often just enjoy the silence as the landscape becomes sparse and the ‘total fire ban’ and kangaroo-silhouette signs flick by. This tradition, though formed more through circumstance than intention, is the only one that is truly ours.

EVERY YEAR, I would help my yiayia set up her tree. We would throw tiny silver slivers of foil onto the branches and they would catch and sparkle in the light. As a young child, I remember thinking that the silver strips hanging from the branches of the plastic tree were the most elegant thing I had ever seen. I loved how my yiayia chose an angel, a small yellow-haired woman dressed in white and made of felt, to place at the top instead of a star. This, alongside her not-too-strict observance of Lent, was the only hint I ever had of my yiayia’s tie to religion. The rest of us didn’t believe – or if we did, we never talked about it.

My uncle’s house is different to my yiayia’s. His trees are bigger and brighter than hers were. The baubles match, teal and silver. There’s a Christmas tree both inside and out. One sits beside us, under the pergola where we eat shaded from the afternoon sun. At lunch there’s lamb cut from the bone, chicken for my young and picky cousins, potatoes swathed in cream. We drink tangy champagne in plastic cups. Dad sticks to lemon squash; he can’t mix alcohol with his medication.

Salads sit in big orange bowls; white flecks of feta shining in the heat, tempting and bright. My aunt makes rocky road from scratch, with cut-up lolly snakes inside, and sponge cake with fruit. It’s a decadent meal, the first of the day, but the afternoon is always comfortable. It feels light, even though our bellies are full.

Janine Roberts, a family therapist, says rituals like Christmas are powerful ‘because they’re active and have many sensory elements to them’, like the act of smelling and consuming food. Food and tradition are connected, and tie into how we understand class. While class differentiation exists in food, Roberts thinks this is not so for Christmas: ‘Rich foods were traditionally eaten at Christmas to demonstrate surplus and plenty and contradict the hardships and scarcities of everyday life, although the significance of this is evidently lost on many people today.’

Unlike Roberts, I don’t think this significance has been lost. My family understands the act of saving for months and then purging, spending the missed coffees and discounted groceries on presents and wrapping paper, cherries and double cream. My yiayia would go without to save enough money for Christmas. Other family members still do the same. They do this not for the love of Christmas, or because they crave decadence – they do it to give our family, particularly the children in our family, what is expected and cherished from the holidays.

Sociologist Les Black says that Christmas and gift giving ‘can be imbued with, and shaped by, subtle classed associations’. China Miéville explores this idea through Christmas lights: ‘You can do a class analysis of London with Christmas lights,’ he says. In poorer homes, ‘the season is celebrated with chromatic surplus’ and the wealthy ‘strive to distinguish themselves with white-lit Christmas trees’.

While writing this essay, I spoke to my cousin who lives in Surrey, one of the wealthiest counties in the UK. His estate, previously situated in a once predominantly working-class area, has become increasingly gentrified. His house, he tells me, is strung in white lights for Christmas.

‘I once tried to buy blue but Vic made me take them back,’ he says. Why white? Well, it’s ‘more minimal, perceived as being classier’. The UK also needs more light because the skies turn dark at 4 pm. ‘We have imported the Scandinavian light tradition; LED lighting, which means loads of white lights. Strings of them are cheap.’ In the UK, Christmas car travel, food, lighting and shopping combined, makes up 5.5 per cent of the country’s total annual carbon emissions.

My parents live in Lower Mitcham, fifteen minutes from Adelaide, a suburb of wealthy families and retirees. Strictly Liberal, not that my parents fit the bill; their first date was a Labor Party event. Lower Mitcham is full of trees. They are plump, and the light filters through their leaves as you walk. Every Christmas, the residents of Mitcham wrap their trees with bows of lilac netting or a rich ruby silk. They do it with such remarkable consistency that my partner and I first assumed it was a council initiative.

Lower Mitcham doesn’t do Christmas ‘lights’. The closest they have are tennis court lights –towering things that reach into the sky, dwarfing garden fences. I’ve never seen them illuminated; the bulbs, the size of soccer balls, remain dark.

Christmas spirit in South Australia particularly blossoms in Lobethal. ‘Christmas shines brighter than anywhere else in the nation in this otherwise sleepy South Australian hamlet,’ according to Australian Geographic. A small town in the Adelaide Hills, surrounded by apple and cherry orchards and by wineries, Lobethal attracts a quarter of a million visitors in December. That’s more than a hundred and thirty times its population. Some properties have over a hundred thousand Christmas lights.

One year, I saw them with my yiayia and some distant relatives. We all looked at the lights together through the car window. I don’t remember much – I must have been eight – but I remember that my yiayia stared at the lights while I focused on the hot, buttery popcorn she had bought me.

WHEN I WAS fifteen, I went to my yiayia’s house to wrap gifts for her. We spent an evening in front of the TV watching Today Tonight, A Current Affair and 60 Minutes as I wrestled with the rolls of paper. Her hands, too shaky from the chemo, couldn’t do it. On Christmas Day, everyone knew that she hadn’t wrapped the presents; they were sealed so tight with tape all along the edges that it took twice as long to open them. We all laughed, until silence came and settled into sadness.

The next year, she wasn’t there for Christmas and I gave up on the charade of enjoying it.

Christmas is tradition and this, as a term, is potent. Psychologist Barbara Fiese argues that tradition functions ‘as an engine of family harmony’. That is to say, the act of repetition keeps families together. The tradition of charades with my dad’s family, eating crayfish with my yiayia or watching the alpacas approach the fence as we drive into Mat’s family’s property, is Christmas.

The tricky thing is that no tradition is static. People die and leave, so we create new traditions with altered family structures. My yiayia is gone, and has been for six years. Only now do I realise that we have evolved as a family in her absence. We have traditions we maintain, foods we cook and memories we rehash.

But however my family has evolved, she remains. Her Christmas traditions linger and create a sense of performativity for the family members she left behind. Now, my mother cooks and my uncle peels the prawns. We are performing her Christmas, even as we impose new traditions. I’m still not sure I like Christmas, but I have come to accept that it is necessary. For me and my family, my yiayia was the ‘engine’ of Christmas. Without her, we can only try our best to keep going.

Share article

More from author

On being sane in insane places

MemoirI’VE BEEN THINKING about how my body inhabits place and how it changes – fluctuating between comfort and pain – depending on the state of my...

More from this edition

The honesty window

FictionA SMALL PRINTED card offered extra towels, if they should need them. They hadn’t been provided in the first instance, Leah read, because the...

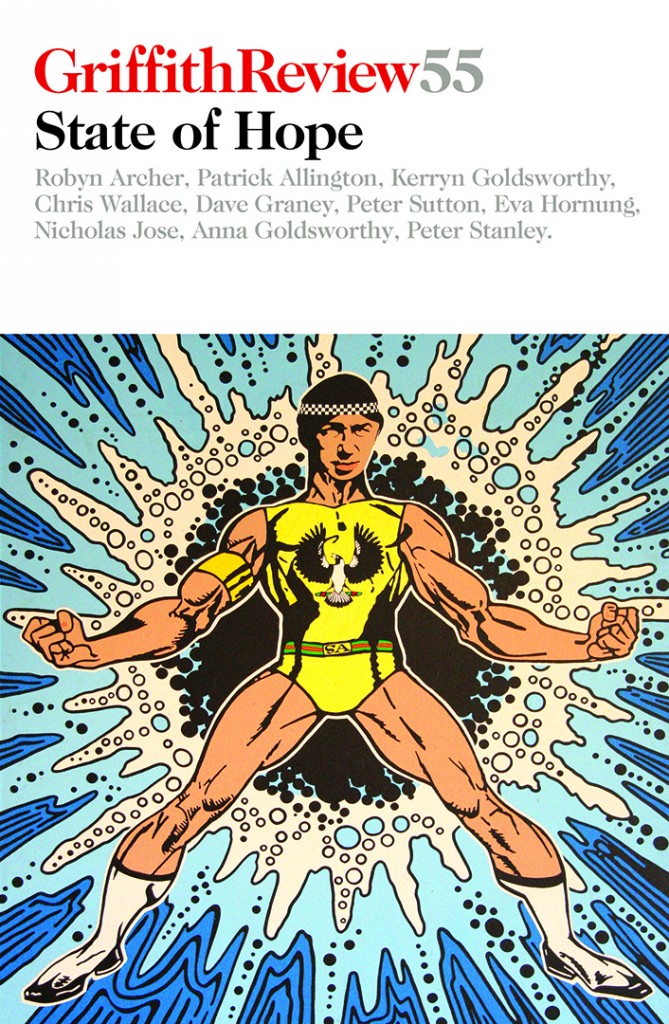

Dunstan, Christies and me

MemoirADELAIDE’S GOLDEN AGE began when the Beatles flew into town on 12 June 1964, electrifying the citizenry out of their country--town torpor into a...

In the dark

EssayA CELEBRITY CHEF declares dairy causes osteoporosis, and cholesterol medication is bad. Parents shy away from giving their children life-saving vaccinations. People are stringing...