Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Dave Witty

Dave Witty is a Melbourne-based writer. His first book, What The Trees See, will be published in 2023 by Monash University Publishing. His work has...

More from this edition

On the forging of identity

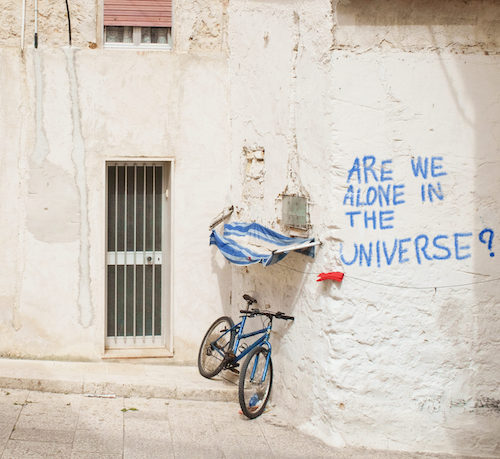

Non-fictionThe night Sartre spoke in Paris can be seen as a hinge in time, the moment when modernity and its focus on individual identity came to the fore after the destruction of the old order. We are still living on the far side of the door Sartre pointed us through. Of course, modernity had a thousand authors. It was the product of billions of lives lived in close proximity. But Sartre, to me, best articulated a modern creed of what it means to be human.

A Little Box

PoetryAnd didn’t I grant you six identical faces, each perfectly plain as the other and a sturdy mouth to clasp shut?

Adhi danalpothayapa

Non-fictionFor all the clans on Saibai, both migrations were distressing, uprooting families from their homelands where they had lived for thousands of years. Nevertheless, knowledge produced from these migrations has been embedded in stories chronicling the changing climate, and shared throughout the generations. A strong sense of pride is conveyed when recounting these narratives of adaption and resilience. Story is the key because the wisdom is in the story.