Featured in

- Published 20160202

- ISBN: 978-1-925240-80-1

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

SARAN IS SIX. His family is new to our small, rural town. He is embarrassed when I ask him about the Hindi he speaks at home. At the parent–teacher interview, Saran’s mother nods while I speak, nods again as the older sister translates. I’ve not yet met Saran’s dad, but Saran proudly tells me he is very very busy at their restaurant.

Jaymez – pronounced James – is seven. He should have started kindergarten (prep) last year. He should have been to preschool. He should attend school more often than he does. He is tightly loved by his lonely single mum who keeps him home for company.

Trudy makes me laugh. She will be six in fourteen sleeps and her confidence is delightful, she can write her name and count to 109. She does Irish dancing lessons and demonstrates an elaborate jig for all the students who are waiting at the bus lines. Her mum came to see me yesterday – Trudy’s folks are separating. I fill an entire page with notes: new addresses, schedules, buses. I can feel Trudy’s confidence slipping away as the ground shifts beneath her dancing feet.

Taylah (the girl) is still four; immature, too young, not ready. Her speech is awkward, babyish and she can’t make all the sounds. She looks dirty and she’s always hungry – our classroom fruit bowl is really just for her. Her mum avoids me, waits outside the school gates, doesn’t talk to other parents. I tried to phone them but couldn’t because the enrolment forms were almost blank: a digit missing from their phone number, their religion listed as catlic.

Taylor (the boy) has just turned six. His parents are going to be the pro-active kind. When I first met them at orientation last year, they asked when the parents-and-friends meetings were held. Taylor has autism and two folders of paperwork. A teacher aide is assigned to assist him. But only from 9 am to 11 am. And not on a Friday. Funding is tight.

Selina keeps me up at night. She made a disclosure two weeks ago. I had to report it. I’ve had a meeting with someone from Family and Community Services every day this week. No wonder she is such an angry little five-year-old. I’m angry too.

Davey has the same birthday as me. He turned six. His mum brought in lactose-free, gluten-free, nut-free, sugar-free cupcakes, trying to appease all the students’ dietary needs. Davey vomited his cake straight into his school bag. His father, Dave Snr., just laughed when I told him and scruffed Davey on the head. The smell of sour milk and cow shit hangs around Dave Snr. so a bit of vomit doesn’t bother him. But Dave Snr. won’t talk about Davey’s aggression, tells me they don’t have a problem with it at home.

Ray is six-and-a-half. He likes holding up the extra half finger to show me. I am not meant to, but I wrap my fingers around his and watch how Ray’s dark skin contrasts against my white pallor. He told me once he doesn’t want to be Koori anymore. I didn’t know what to say to that. Our once-a-fortnight for half-a-day school counsellor probably wouldn’t know what to say to that either. Making contact with a local elder is on my list of things to do.

I AM THIRTY-EIGHT and tired. I’m only a third of the way through my class roll, a list that hurts my heart if I study it for too long. But I know what to do with these students. I’m an excellent teacher. I know how to bring them together. I am able to create a feeling of family and safety and security. In my classroom they know they can take risks and try new things and experience failure while being supported by me and by each other.

We feast on stories together, devouring Where The Wild Things Are and savouring There’s a Hippopotamus on Our Roof Eating Cake. They come to love the taste of reading, the flavour it adds to their life. In small, bite-size pieces I show them how it’s done – how they can make meaning from the words. Their eyes sparkle when they realise they can read, when they realise they can nourish themselves.

There is something about giving the gift of reading that creates trust. These little ones believe me when I tell them they are writers. We put a sign on our door:

SSSHH!

Writers at Work

Our room comes alive with a hushed concentration. I join them in the writing process, my texta scratching onto butcher’s paper, modelling my love of writing. I field the occasional question:

How do you spell unicorn?

Does motorbike have a ‘a’ in it?

Can we put ‘crocodile’ on the word wall?

We explore the world of mathematics. Every day we count to one hundred, by ones, by fives, by tens. We look at the hundreds chart and become pattern detectives, noticing, questioning, creating. We solve problems, putting the big number in our head with a theatrical tap and counting on with our fingers.

Watching children learn is a beautiful and extraordinary experience. Their bodies transform, reflecting inner changes. Teeth fall out. Knees scab. Freckles multiply. Throughout the year they grow in endless ways and I can almost see their self-esteem rising, their confidence soaring, their small bodies now empowered. Given wings.

They fall in love with learning.

It is a kind of magic, a kind of loving, a kind of art.

It is teaching.

Just teaching.

Just what I do.

What I did.

Past tense.

IT WAS A Thursday afternoon in November. I can so clearly remember it was Thursday. All day I had been trying to complete the end-of-year assessments for my last six students; a task that requires a minimum half-hour one-on-one with each. But that morning the principal had been in to film our literacy block for the school’s participation in the Collaboration on Student Achievement (CoSA) project.

After recess, students from Year 1 came into my class for maths since their ability required they worked at this remedial level. I couldn’t assess with extra students in the class. Besides, they couldn’t afford to miss their lesson.

After lunch I set my class to their much loved but only occasionally enjoyed ‘free play’. My six students for assessment were denied the privilege as I hurried them through the testing regime.

As the afternoon went on, the class became restless. Children started bickering over Lego, the game of robbers became wild and rough and students were demanding I look at what they had done on the iPads.

‘Not now!’ I kept saying, turning them away with a flick of my hand. ‘Not now!’

I was testing my least able student. He stared at the laminated list of sight words, one hand twisting his school shirt into a rope-like bundle. I tapped my finger against the next word: little.

Come on, I thought. Hurry up!

The class was getting louder.

Come on.

‘Try the next one.’ I shifted my finger down the list: and.

Three boys went running past, their mouths farting out motorbike noises.

Two girls were squabbling in the corner.

One boy was alone. Listless and tired.

‘Let’s try the number work,’ I suggested brightly, slipping away one laminated sheet for another. ‘What’s this number?’

‘Four!’ He is triumphant but I temper my smile. According to standard testing procedure, we are not to give feedback. It is his first correct answer but I can’t congratulate him.

He twists his shirt and looks away.

Blocks are being stacked as a tall and wobbling tower.

The motorbikes are racing.

Robbers fighting.

I’m pointing to the number six and I can hear my student thinking this is the tricky one – is it nine or is it six?

The blocks crash and the sound frightens me.

There is an odd silence.

A knock at the door.

The assistant principal. ‘I need your assessment results. Canberra just rang asking why our data isn’t entered.’

It was a desperate feeling. A realisation. I was trying to do the impossible. I was destined to fail.

There was pain in my chest, my heart clenching and screaming LET ME OUT.

A cold sweat shivered on my skin.

This is it, I thought.

This isn’t teaching.

I’m not a teacher anymore.

‘YOU’VE RESISTED THE urge for too long,’ my psychologist tells me. ‘Fight or flight is a powerful instinct. Cortisol has been dripping into your system with every stressful day.’

She mimes the drops of cortisol with her hands.

‘Your body doesn’t know if stress comes from work or a tiger chasing you. It responds the same. It tells you to do something – your body wants you to react.’

Resisting fight or flight.

That’s what teachers do.

For two weeks I cannot get out of bed.

I am numb.

How did I get here?

TWELVE MONTHS LATER I’m still turning that experience over in my mind. My fire has turned to ash, burnt out from relentlessly keeping account when I should have been teaching, reporting when I should have been listening, making standard when I should have been making a difference.

How did I get here?

I was burnt out because successive Australian governments – both left and right – have locked Australian education into the original model of schooling first established during the industrial revolution. Each decision made keeps us stuck in an archaic learn-to-work model, now complete with ongoing mandatory assessment of our student’s likely productivity and economic potential.

Fundamental to this model is the idea of standardising.

Standards, standardising and standardisation.

Making every kid the same.

Making every teacher the same.

If I was successful in my job, that’s what would happen.

Based on that, I don’t want the job any more.

My story isn’t special. My class roll wasn’t disproportionate in the number of students with particular needs. Every primary teacher, regardless of their location, has a roll similar to mine. The names might vary, the ages and issues too, but ultimately every class roll is a story, if someone would just care to listen.

But contemporary Australian education doesn’t want to hear the story of my class roll. Contemporary Australian education wants test results and data. Pressure to meet the standards, regardless of the needs of individual students, means that the little details must fall away. There’s no time for stories.

Mandatory.

Standards.

Imposed.

There’s something sinister happening to this profession that I loved.

And it breaks my heart.

And it burnt me out.

We don’t trust our teachers anymore.

SIXTEEN YEARS AGO, I took my first teaching position in London. It was Grade 6 (twelve-year-olds) and they were preparing for their SATs: standardised tests that determine which high school they can attend. I was instructed not to teach art or PE, only what was on the test until the exams were over and then I could teach ‘whatever I wanted’. On the morning of the first exam a student named Alice Heart ran into our classroom sobbing. She clambered onto my lap like a much younger child and cried: ‘If I don’t get a good result I won’t get in to St Ursula’s. My mum will be mad.’ I held her and thought, This would never happen in Australia.

And yet, here we are. Doggedly pursuing a ‘world-class’ education program by following in the footsteps of big brothers Europe, the US and Asia. The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) is conducted annually for students in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. Each student receives individual results but the collective results for each school are made public on a website called My School and a list of the top schools published in league tables.

I’m rarely required to ‘teach’ anymore. Apparently I’m more valuable as an assessor, an examiner, a data collector. I have had to dull my once-engaging lesson sequences. Now I must begin by planning the assessment, consider how students will show what they’ve learnt and pre-determine what they are going to learn. Nothing can be left to chance. It is mechanical and rigid and driven. Brightly coloured spontaneity fortified with professional judgment has been replaced with black-and-white standardisation and a judicious critique of every child’s work.

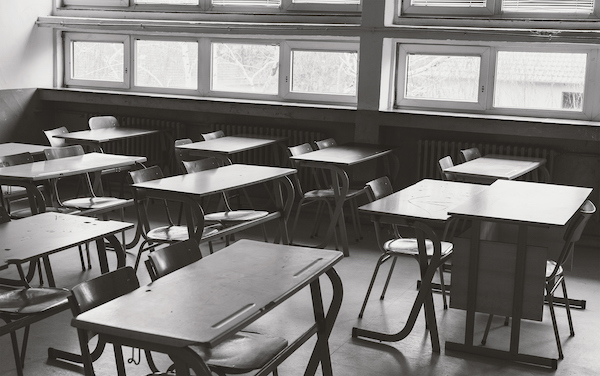

Classrooms have become test-driven places where students learn to colour circles marked A, B, C and D. Even the classes not subjected to NAPLAN endure ongoing formal assessment from teachers turned examiners who must procure benchmarks, reach standards and gather data.

I’m not myself when I am testing. I have to be indifferent. There’s no warmth, no encouragement. I feel guilty and I hate the way my students look at me: expecting praise, getting none. Their eyes pierce mine: who are you? Where is my teacher? I become no more than the slippery, laminated sheet encasing the testing regime.

This testing costs me dearly – it costs me time with my learners, it costs my energy, it costs me the trust of my students. But it’s costing Australia too – the price of our young minds and their desire to learn.

Standardised testing and, more broadly, standardised education is costing teachers too. Over the past sixteen years there has been exponential change in primary education in Australia and most of this change has been imposed on teachers. Each change limits my control as classroom teacher, undermines my judgments and detracts from my ability to act as a unique and educated professional. My career has not been long but in that time I have endured the imposition of initiatives such as A-E reporting, NAPLAN, My School, Professional Standards for Teachers, Quality Teaching Frameworks and a national curriculum. I have become morally and ethically conflicted as I am drawn away from my students and their needs and drawn toward checklists and continuums.

And with each new agenda comes paperwork, so much of the stuff that it piles up on my desk and crowds out the note from Donna’s mum about her asthma and the book I wanted to share with Toby and the picture Kalindah has drawn for me.

It’s happening everywhere, people tell me. The red tape is horrendous. Every business is the same.

But schools are not businesses. They’re not industries.

Schools should not be framed by business models. They should not be viewed in terms of academic results based on productivity. When we look at schools in this way we lose sight of what matters. We lose sight of students.

Schools are unique places where amazing things should be happening for young Australians. And, as such, extraordinary and unique frameworks and policies should support them. Teachers and principals face continual pressure to make schools ‘like something else’.

But schools aren’t like anything else.

They’re schools.

TEACHING – GOOD TEACHING – is both a science and an art. Yet in Australia today this incredible and important profession is being reduced to the sum of its parts. It is considered something purely technical and methodical that can be rationalised and weighed. But quality teaching isn’t born of tiered ‘professional standards’. It cannot be reduced to a formula or discrete parts. It cannot be compartmentalised into boxes and ‘checked off’. Good teaching comes from professionals who are valued. It comes from teachers who know their students, who build relationships, who meet learners at their point of need and who recognise that there’s nothing standard about the journey of learning. We cannot forget the art of teaching – without it, schools become factories, students become products and teachers: nothing more than machinery.

Here’s the thing: a national curriculum does not guarantee engagement or achievement, no matter how glossy and persuasive the buzzwords are. And regular standardised testing simply makes people better at sitting tests. Imposing goals and standards on teaching professionals only serves to squeeze from them the last few drops of goodwill they may have held.

In my last months as a teacher, I had become scared. I was scared of teaching outside the prescribed model because it may not fit the current trend. I was scared my teaching would be judged critically. I was scared of neglecting students by prioritising paperwork over their needs. I was scared of a workload that was in no way related to teaching and learning.

And now I’m scared for all the children in primary schools across Australia, because I think more teachers – more good teachers – are going to leave and in doing so, our country’s very foundations become decidedly shaky.

Who will teach our children?

I can’t do it anymore.

I CLEAN HOLIDAY apartments now but sometimes, while I’m smoothing fresh linen over the beds, I imagine a student called Australia. Who would teach her? How would she learn?

I dream up a new paradigm of education, something that isn’t a reconstruction of an old industrial model.

What we need right now is imagination.

We need ingenuity, creativity and a profound commitment to our teachers, schools and students.

I place tiny soaps on folded towels and I think. I think about schools focused on ‘students and learning’ not on ‘performance and results’. I think about how there isn’t any fact I can teach a kid that they can’t Google for themselves, and what this means for them as learners. I think about creating life-long learners. I think about technology and how to teach skills of communicating, synthesising, critiquing and creating within the World Wide Web. I think about how to convey the emotional intelligence required to navigate social media and Web 2.0.

I think about all the learning students do that can never be measured, quantified, weighed and accounted for. How I’ve taught them to share or co-operate or have confidence or tie their shoelaces. Where does that fit on the NAPLAN data?

I think about students learning for the joy of it, not for the test of it – learning science because they love it, not because ‘they perform well’ in it.

And as I push the vacuum cleaner around the room, listening to grains of sand rattle through the tube, the dangerous ‘what-ifs’ pervade my thoughts.

What if we encouraged quality long-term professional development for our teachers with monetary remuneration? What if we afforded teachers time enough to do all their work? What if we gave teachers and learners access to specialised resources in the form of skilled professionals? What if every school had a full-time counsellor?

What if we trusted teachers and reconfigured their paper-based checklist-focused goal-setting accountability-driven jobs so they could focus on their students? What if we used new and different measures of achievement? What if we placed equal value on personal development? Social achievement? Effort? Resilience? Creativity?

What if we stopped testing the socio-economic gap NAPLAN constantly reflects and, instead, tried to build bridges of learning over that gap?

What if we didn’t compare ourselves to everyone around us?

What if we refused to reduce teaching to a formula?

What if we focused on producing top-quality teaching graduates who understand primary teaching is all about positive relationships and bringing out the best in kids?

What if I could teach Australia to think for herself?

Listen to Gabbie discuss ‘Teaching Australia’ on ABC RN’s Conversations with Richard Fidler:

Share article

More from author

In an unguarded moment

Essay IT’S EARLY ON a Friday and the usual morning hustle of a school day is playing out in my kitchen. Olivia, ten, is dressed...

More from this edition

The good old days

EssayOver the last thirty years I have sought to explore how our top political executives exercised their power, whether they were prime ministers, ministers or departmental secretaries. My books include a study of the ways that the Australian Cabinets have changed over the past hundred and fifteen years, and two books on particular prime ministers, one from each side of the political divide. My interest has always been on how they do the job, how they define their responsibilities, what being prime minister means. Perhaps inevitably, when current circumstances are compared to, and placed in the context of, past leaders, it is the continuities rather than the differences that strike me as the most significant.

On the abolition of Question Time

GR OnlineIN 2014, EIGHTEEN years after Paul Keating lost the prime ministership, a collection of his prize insults appeared in print. The fact that Black...

Avoiding the simplicity trap

EssayAUSTRALIAN PUBLIC POLICY labours under the weight of illustrious ancestors. There was, in this country, a period that has been labelled the ‘Age of...