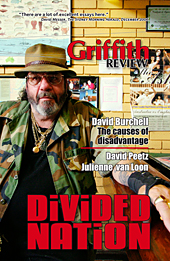

Featured in

- Published 20070306

- ISBN: 9780733320569

- Extent: 280 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

FOR SOME YEARS, once upon a time, I lived in a little house on a cliff in a coal-mining village north of Wollongong. The spectacular views along the rugged coastline drew the eye to the industrial city’s bustling harbour, the steaming and flaming chimneys of the factories that earned the city its “steel city” moniker. Million dollar views, guests would gush, as they lingered on the balcony, spotting albatrosses and sea eagles, dolphins and giant schools of fish just below the surface. Even the occasional whale.

During the resources boom at the start of the 1980s, the horizon was also dotted with container ships. Giant rust-encrusted vessels with utilitarian names from far-off ports waited to take the coal out, and bring the iron ore in. Ten, twenty, thirty ships could sit high in the water waiting a turn at a coal-loader that could not keep up with demand, just as they now wait off the coast of Central Queensland and Western Australia.

Once loaded, the ships would sink deeper in the water and we would watch them head north on the long journey to deposit their bounty and power the Japanese wonder economy.

Then one day it stopped. Where there had been scores of ships queuing to take away the dense black coal – which had provided just enough warmth and income for three or four generations of miners, and thousands of generations of Dharawal who found both physical and spiritual sustenance on the escarpment and in the ocean – all of a sudden there were none.

No ships waited to take the coal away, hardly any ships waited to deposit the iron ore destined to trundle along the conveyor belt and become girders and rooves and fences and pipes. The economy shuddered as the long legacy of the oil shocks of the 1970s continued to reverberate locally and globally. Steel and coal industries were in crisis everywhere – caught in the pincers of shrinking demand, under-investment, atrocious productivity, rigid work practices, poor planning and half-baked policy. The domestic market collapsed. As orders fell away, jobs went with them. Tens of thousands lost their jobs, in the mines and factories and in the businesses that had grown up to service them. These were not glamorous jobs, but reliable, regular work that needed to be done, paid tolerably well and provided a constant stream of migrants with their first work in Australia.

The enormity of the crisis was clear and personal. My neighbour had the gruesome task of putting on his policeman’s cap and investigating suicides of blokes he once drank with, who had found life unbearable.

Watching the disintegration of a community from a distance seemed inadequate, so I set out to write a book – Steel City Blues (Penguin, 1985) – about what was happening and why. Every day for months, I trundled down the highway, talking to tearful managers, a mayor (later murdered) with a vision, women who had fought for jobs in the steelworks only to be the last on first off, sons of men from Yugoslavia and Italy and England and a dozen other countries whose apprenticeships were cut short and who blamed the “slopes” [Vietnamese boat people], old men who had taught themselves English waiting in line in the steelworks canteen (“a milkshake please”), others who couldn’t imagine what else they could do but go down the mines, kids who left school at fifteen and dreamed of becoming famous and successful, union officials with an agenda, management consultants with a plan, activists who wanted to foment revolution.

And there was a revolution of sorts. Those most affected fought to be taken seriously, to be treated with respect and decency. In October 1982, a group of miners stayed underground for sixteen days and won better redundancy payments. Thousands travelled to Canberra in a protest that culminated in breaking through the barricaded doors of Parliament House and flooding into Kings Hall. It was the beginning of the end of the government of Malcolm Fraser, who lost to Bob Hawke in March 1983.

AS I SAID, all of this happened once upon a time, in a distant age, when the notion of a million dollar view was a ridiculous joke. Now it is a statement of fact, the little house we built for $35,000 and sold for $110,000 has grown and is now actually worth millions. The view remains the same, but the neighbourhood is richer and tidier – a tourist destination; coal mines closed, steelworks beautified, a university the largest employer in the city.

Once upon a time, before the social reforms that encouraged cohesion, creativity, multiculturalism and reconciliation, before the economy was deregulated, the dollar floated, industry restructured and the economic framework that facilitated the long boom of the last fifteen years established.

For many years, the fruits of these policies were highly contested and unevenly distributed. Pockets of high unemployment lingered well into the 1990s – despite spectacular growth, the transition from an economy underpinned by mining with a significant overlay of manufacturing to one where more people were likely to work in services was hard. Economic and social reform was the order of the decade from the mid1980s, and it paid off for most people – but not without some resentment.

IN HIS FINAL speech to parliament as Opposition leader in November 1995, John Howard decried the damage that had been done by these reforms: “The worst legacy of this government … will be the extent to which it has divided the Australian community, the extent to which it has put one Australian against another, the extent to which it has presided over the widening gap between rich and poor … [Paul Keating] will wear the mark of dividing Australian society, of being a leader who has wounded and wrecked rather than healed and united, of being a leader who has seen partisan political advantage in setting one group against another.”

Throughout his prime minister-ship Howard has been adept at managing division, and he has not shied away from fostering it. His government has been blessed with a buoyant economy and the flexibility this money provides.

The long boom of the past decade and a half has put paid to the old shibboleth that Australia cannot manage booms. Over the last few years, unemployment levels have fallen to record lows, the economy has continued to grow respectably without overheating, gross domestic product per person has increased faster than in comparable countries, and in the decade to 2003 income has increased by about 24 per cent for people living in both rich and poor postcodes.

Yet, over the same period, inequality has increased. The salaries of chief executives have increased from eighteen times the average wage to sixty-three times, conspicuous consumption by the affluent to some degree relies on the low wages paid to those in the hospitality, retail, childcare and agricultural sectors.

Generally we prefer to avert our eyes from those who have not done so well from the boom. Home ownership remains the key to economic wellbeing in this country, but as prices have increased it has become less affordable for many, just as others have made small fortunes from property speculation. Each year, more than $200 billion is collected and redistributed through the vast array of family and income support payments, yet single people living on welfare make do on $72 a week below the poverty line.

Former US President Bill Clinton once remarked that what a country does with its prosperity is as much a test as what it does when times are hard. The longterm scorecard on Australia’s performance in this boom cannot be written yet, but as the stories in this issue illustrate, it is not likely to be as uncomplicated or generous as many would hope.

In December 2006 in his first speech as Leader of the Opposition, Kevin Rudd echoed John Howard’s earlier critique when he said: “This country is engaged in a battle of ideas for Australia’s future … In an absolute nutshell that is the divide between us – a view that says it is about me, myself and I and an alternative view which says that we are about an Australia which recognises that individual hard work, achievement and success are to be encouraged and rewarded, but at the same time we cannot turn a blind eye to the interests of our fellows human beings who are not doing well. That has been the divide between us for a century and remains the divide today.”

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC division is something that can creep up unexpectedly if you don’t read the signs right. Like a southerly buster blowing up the coast, first there are a few white caps on the sea, then a dark line in the water, and before you know it a gale that drops temperatures and debris in its wake. At the beginning of 2007 two states were still booming, one was in recession and another was on the cusp of recession. The luxury of having more money and ideas looked set to expire.

Social division is a bit like that too, hard to predict, but impossible to ignore once it arrives. It can also be whipped up in a fury of rhetoric, ideology and spin, even in a relaxed and comfortable place like this. The naming and shaming of refugees, Muslims and Aboriginal people has proceeded with tacit, and at times explicit, political endorsement.

This is a tactic which has delivered for some politicians during the boom, but is at odds with the best of the Australian tradition. Egalitarianism and tolerance have had a tough time remaining the dominant values in recent years. The boom has softened this attack, but the corrosion has begun and if things turned bad, as they did in Wollongong in 1982, the repercussions could be considerable. The Sydney riots in 2005 demonstrated, in some communities a sense of grievance is not far below the surface.

The 2007 election campaign will be a test of how serious this is, and how resilient we are. A national survey by the Social Research Policy Unit at the University of New South Wales on the essentials for reasonable wellbeing reveals that everyone – rich and poor – considers being treated with respect by others as fundamental, more important than having lots of stuff. Respect transcends division and can be applied to all aspects of our lives. It is time to listen to the stories of those who have missed out, or been made invisible and try to understand, rather than turning a blind eye or reacting with a flash of fear.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

On becoming a Jew

MemoirIf you ever forget you're a Jew, a Gentile will remind you.– Bernard MalamudBROOKLYN LAUNDRY, 2002: Sometimes I am asked how it feels to...

The exiled child

EssayThere have been many times in my life when people have come to negative conclusions about me, and many terms applied: juvenile delinquent, alcoholic, drug addict, drama queen, borderline personality disorder, self-destructive, hysteric, depressive, neurotic, phobic and hypochondriac. But I've discovered a new one, and according to the literature it may be at the heart of all the others: chronic trauma survivor.

Boom! Excursions in fantasy land

EssayMIDLAND: RECENTLY I watched a small group of drunks on the pavement across from the Midland library swinging punches at each other. There were...