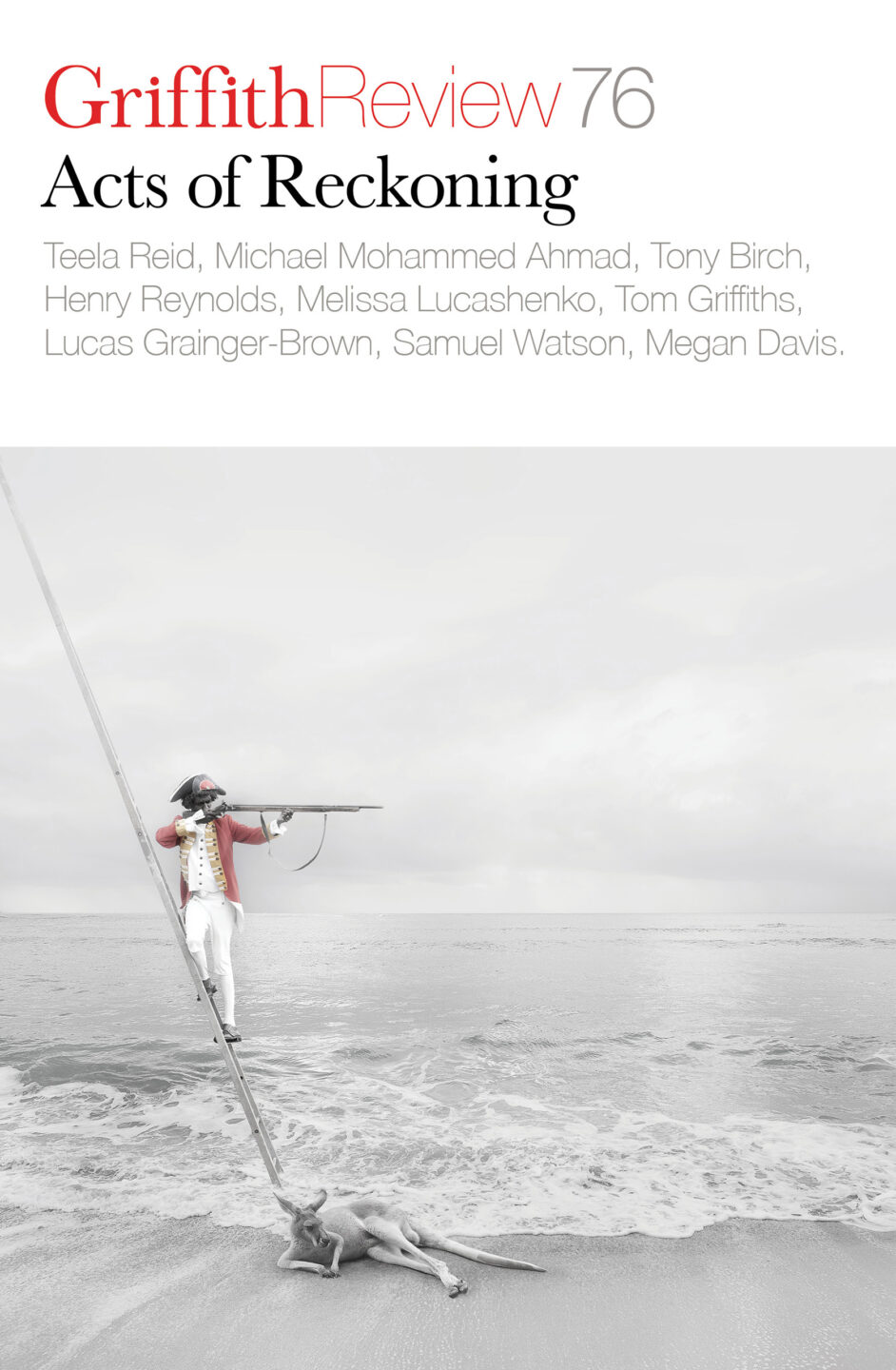

Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

In the second of a series of intergenerational exchanges and reflections on the links to and legacies of the Whitlam era in the run up to the fiftieth anniversary of the 1972 election – a collaboration between Griffith Review and the Whitlam Institute – a federal senator and land rights activist talks with a graduate First Nations constitutional lawyer about Indigenous affairs across the past fifty years and into the future.

PATRICK DODSON: It’s a bit hard to compare the sort of cataclysmic change that came about when Gough Whitlam took office and – in a very short space of time – implemented a range of reviews or changes to the fabric of Australian society, certainly to the status of Aboriginal people. We’d been lingering on the vine very much under the control of officers and assimilationist dictators and repressive kinds of regimes. Gough’s land rights promises, his concern about sacred site protection, his concern about equity – that there be a real opportunity for Aboriginal people to have a say and to have a Voice to Parliament, to direct and guide the Australian nation as to where we wanted to go under a policy of self-determination, to bring into that an international perspective based on the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – that lifted Australia out of this sort of backwater. Combined with his own charisma, his own dedication, his own forthrightness – well, having grown up with the assimilationists’ attitude, the appearance of Gough [meant that it] took a while to understand what the heck was happening! It was a whirlwind – but a very, very pleasing whirlwind. The legacy is still here and it’s taken a while to grasp the initiatives that he undertook and delivered upon.

BRIDGET CAMA: My first memory of hearing his name was my parents reflecting on Whitlam’s three years and the things he achieved in that time. His dedication to equity directed the path I wanted to take and some of the things I wanted to achieve. My parents would talk about everything from education to justice. Seeing that iconic image of Gough pouring the sand of country back into Vincent Lingiari’s hands [at Daguragu], that sticks in my memory, how powerful that was, and the sense [that things could] change in this country. It showed that someone just has to be brave and follow the things that they believe in – of course, that comes with criticism and risks. But someone’s ethics and morals can shine through. And it only takes one person to be brave, to take up that leadership, to create such change and such a whirlwind in such a short amount of time.

The impact that has on future generations, well, we’re still feeling it today. As a young person, I definitely feel the energy around that and it gives me the ability to say things still need to be done – and we want to make sure those things eventuate within our lifetime.

I saw the law as a good lever or mechanism to try to effect change when I wanted to understand my purpose in the world. I saw the impact that the law has on people’s lives – every day, and systemically – and as I read about civil rights movements around the world. There’s a lack of education around civil rights movements led by Black First Nations peoples and by our Elders: the fight’s been going on for decades. You gravitate towards that as a young person who wants to make change, who wants to feel as though this is a country that you can be proud of, with a national identity that reflects all of us as Australians.

I don’t think we’re there yet.

PD: For me, the law usually conjured up the police and criminal justice. The notion of political civil law and constitutional law were always couched around the land rights struggle: you know, we want recognition of the fact that you stole our land and we want it restored. But the capacity to restore it wasn’t necessarily initially thought through as some sort of legislation – we needed it restored and we needed agreements about what we could do on our lands.

What resonated for me were the equity components – understanding the qualitative uniqueness of who we were as people within the environment of Australia. The idea of justice and the need for equality based on advocating for a way of life driven by our values and our systems butted up constantly with the social protocols, the expediencies and freedoms that the white folks had. That morphed into the need for rights in society and the Western legal system – like land rights in the Northern Territory, like a structured Voice to Parliament to raise our conditions.

Even the assistance Whitlam gave in legal aid – he set up a legal system that you could use to get someone to represent you in the courts. Whether it was about kids being taken away or how you were treated by someone or an offence that you were accused of. The law was a very narrow criminal justice scene; it wasn’t necessarily seen as a lever for political liberation initially. It’s gradually become that. Police, not the courts, were the law.

Through Whitlam we realised that the political solutions to the social inequities that we were experiencing – and the lack of real recognition of who we are as peoples – was part of the international arena. People started to look at how the United Nations operated, how other Indigenous groups around the world were treated by domestic governments, how we might form affiliations and advance political interaction with the dominating governments of the day. The international arena helped give us some confidence and hope that solutions in Australia were not always going to be found within Australia. We needed external pressure on the politics of Australia to achieve that.

Whitlam’s standards for Australia were obviously based in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and also in the enactment of the Racial Discrimination Act. That was a very big move: you could seek justice from, say, the real estate agent – forever and a day it had seemed real estate agents denied people tenancy, so there was a bit of relief in being able to appeal to a law like the Racial Discrimination Act. It was like coming out of a smoke haze to see clearly that there were other ways that we as Aboriginal people could be treated and that we could interact with civil society – if there was some enlightenment we could achieve better things for ourselves.

The First Whitlam Ministry [Whitlam and Lance Barnard], they held the reins for two weeks – the cabinet of two. And they had a decent public service. It was six years after the 1967 referendum when Whitlam got into power, and [he had] a whole range of public servants, very experienced, very knowledgeable, who hadn’t seen much of the change that was promised by the referendum carried through.

We don’t have that same quality of public service system today, which is unfortunate because we have a range of things to be done that still needs it: the Makarrata Commission has to be set up; truth-telling has to be implemented. A treaty process has to get underway and we’ve got to get constitutional entrenchment of a Voice. Without really good public servants who can rise above the politics, it’s very hard to achieve those things.

During World War II, Gough spent a fair bit of time in the Northern Territory at Gove in the air force and saw how Aboriginal peoples were being treated by the system. He saw the impact of Christianity: he used to say to me ‘Are you the priest or are you the lawyer?’ – he used to get me and Mick [Dodson] mixed up a bit. When I said I was the priest, he said, ‘Oh yeah, we know what damage you blokes have done!’ He probably had more time for Mick as a lawyer!

BC: For lots of Australians, the law probably feels like a kind of alien world at the best of times – and most Australians probably hear the word ‘constitution’ or ‘constitutional’ and think, that isn’t even something on my agenda. Most young people think that. A lot of the work I’ve done is breaking down that barrier, explaining that the Constitution is like Australia’s birth certificate. First Nations peoples need to be recognised in a non-symbolic way within that Constitution because it creates our future as a nation. It’s important to think about things like nimbleness and aspiration and generosity in this really specific space.

The theme of this edition – reckoning, truth-telling – this kind of work has the ability to get our nation to a point where we can really start being honest with each other, working towards a time when we have settled the accounts and got to a point where both sides are at the table as equals, able to address the injustices of the past and talk about how we move forward as a country.

That’s a bigger picture of what reforming the Constitution can achieve.

But it comes back down to self-determination, having a body that allows First Nations to have a voice over issues that affect us – which is not something new. This has been an ask from the First Nations peoples for decades – it was addressed by Gough Whitlam during his time. Australia has the opportunity to address our past and address our First Nations peoples. We aren’t a problem and we shouldn’t be viewed as one. It’s time our Constitution reflected that and gave us the ability to take our rightful place in our nation, to have self-determination and to have agency over our lives.

PD: If we were generous we would have solved these problems by now. We can quantify generosity by the success of the 1967 referendum: more than 90 per cent of Australians voted in favour of that referendum. The substantive matters that we’ve got to resolve go to the ways we deal with the narratives of settlement and colonisation. They go back to the very Doctrine of Discovery that underpins the construction of terra nullius as the means by which to disinherit and disenfranchise Aboriginal people.

Terra nullius was probably the closest matter that I ever got to contemplate in terms of the Constitution: how to get rid of terra nullius. And then how to deal with the question of sovereignty – the courts weren’t capable or were not permitted to deal with sovereignty.

The future shape of our nation has a good grounding from Whitlam – a really good grounding. The elements are still there – to be generous, to be accommodating, to be transformative of matters that are in need of transformation. Of getting towards a celebration of a greater level of unity and appreciation and respect of our unique diversities. We’ve become a multicultural country – and Gough was part of that as well, breaking the mould of the old Anglo-Celtic dominance of our civic society. We haven’t quite got to celebrate the fullness of multiculturalism but as we move towards something like a republic, these things will happen. And of course…the injustices to the Aboriginal people have to be resolved before we can get to a republic.

There are many opportunities for us as Australians. But [they] require generosity of spirit and an openness of heart and a preparedness to go into those realms of the darkness with confidence that we’re capable of coming out the other side and seeing the sunlight. We’re not all going to be trapped in some dark vortex that takes us nowhere. Whitlam opened that up and it’s given us a better sense of who we are as modern Australians.

The younger people are coming through; you obviously have a new road to hoe here Bridget. But all the elements are there for something like what Gough created, and if we can get a successful referendum supporting the Voice in the Constitution, that may give us something like the celebration that we had back in ’67. When that referendum went through, and then the social policy reforms that were to flow on, the bipartisanship that was meant to happen at the political level… I think Gough was a bit tired of waiting for Billy McMahon and some of those other people to move along. And so [in 1972], he and Barnard, they got on their horses and took off – which was great.

I’m not sure whether we’ve got the right calibre of politicians in our current parliament but we do have some really good people who are capable of grasping the vision that Gough and others have given to us and achieving even better things for us as a nation – and as an international citizen.

Gough had some great people advising him. He had Nugget Coombs. He had these great Aboriginal leaders – Joe McGinness and others who were all part of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders movement that led to the referendum in 1967. The wisdom of that time was about social equity, social achievement – the great leadership that came out of Victoria with Mr Cooper and others, calling on the parliament to give us a representative back in his day, and the Day of Mourning 1938. This history is not readily understood – and it’s not taught. So every time there’s a move by Aboriginal people to assert their interest, we go back to square one as it being [seen as] some kind of challenge to the power and privileged position of non-Aboriginal people. Gough seemed to be aware of these trends and tried to capitalise on them.

Gough upset that in a very skilful and meaningful way. He created the family court; the Morrison government has destroyed that. He created a whole range of support services for people; now you can’t get support unless there’s some draconian measure attached to the privilege – and if you don’t comply, you can get penalised. The mentalities are quite different.

Gough wanted to make sure that there was equity across the board in all theatres of life. First Nations peoples obviously needed justice – that was clear as anything to him, but so were the needs of workers, families, students. Equity across the fabric of our society was what he was trying to achieve.

Australians understand that recognition of First Nations peoples has drifted on, and for no good reason. Take the Statement from the Heart’s offer of a Voice to Parliament – it’s advisory; it has no control over parliament and it’s subject to the legislative machinations of a parliament. What a generous gesture that is – I think many Australians realise the uniqueness of that. It’s almost a surrender document in the sense of, alright, you blokes have won; here’s our peace token. Please pick it up. You can’t have a decent fight with us because every time you do you lose, like Mabo; like so many other things. So at least pick up the peace token we’re putting on the ground for you.

I think many Australians feel that when there is a referendum called on this matter it will be a very successful one: that’s my gut feeling.

BC: Absolutely. I really do I think it’s time. The support for a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament is so overwhelming. It’s an invitation to the Australian public. It deliberately wasn’t presented to parliament because we have had those generous acts in the past, such as the [Yirrkala] bark petitions, presented to government – and they end up on the walls of Parliament House. If that’s not the most disrespectful thing that can happen, I don’t know what is.

These acts of generosity and the constant push back of these acts; let us realise that the people are going to have to change this. What happened in ’67, that’s what’s in the rumble, you know; it’s happening again.

But we are living in a different time. Us young ones, we are privileged. We live after the Racial Discrimination Act was passed – we did not have to deal with a lot of those things that our older people have had to deal with, which means having energy to go forward and make sure that those things don’t happen again. But to move forward, our history – our shared history and what that means: invasion and the colonial project that’s happened since – has to be recognised. That comes through just being honest with each other. The proposal for a First Nations Voice is really the epitome of the love that First Nations peoples have and the stamina to sit down and go through consultations yet again.

I think young people have lost a little bit of faith in the accountability that the UN or any international gaze might have in reality on the ground. That’s not to say that those mechanisms aren’t important and that they shouldn’t be engaged with. But in terms of advocacy I think it has lost a little bit of traction. We’ve seen the statistics: they’re all there on paper. And yet nothing changes and there’s no real outrage about that. That’s disappointing. These are people’s lives and communities. You start to think, how do we get people activated, or to feel so strongly about an issue that you would expect anyone to feel strongly about? This goes back to people being held accountable, people holding governments accountable, and to making ourselves heard.

PD: In terms of accountability, of international focus, something like the Black Lives Matter movement and the renewed focus on deaths in custody: these are important components and we shouldn’t lose sight of them. But I’m thinking of the UN declaration on Indigenous people’s rights – Canada has adopted it and implemented it in a domestic manner. It has sought to reform its legislative frameworks to comply with the measures within that declaration. That should jolt Australia into some kind of embarrassment.

So international developments are still very important: some nation states are owning up to the awful consequences of their assertion of sovereignty over individual nations, Indigenous peoples, who were there before them. We can’t remain closed within Australia; solutions won’t come from that. This has to be driven by our leaders – and by young leaders too. But there’s a real need to have other references so that people can understand these are achievable measures: human beings in other parts of the nation, other parts of the globe are capable of making these decisions and their world hasn’t collapsed. In fact they’ve probably enhanced their world.

BC: We have so much to give; so much has been given time and time again. Now it’s about the other side meeting us there and having that dialogue. There’s so much power in having input from First Nations peoples who have lived experience, making sure that it is coming from the ground up, a bottom-up approach, to make policies and laws richer and more well informed through a constitutionally enshrined Voice to Parliament.

We have bodies that already advise parliament: it’s not a crazy, out-there proposal. We need that political Voice. It’s not going to be the solution to all of those things, but it is definitely a way to ensure that self-determination of First Nations peoples and that right to self-determination are upheld and equity is available to those who require it. And that’s a part of that restitution as well, right? We can’t just pay lip service to it anymore. If [a constitutionally enshrined Voice] doesn’t work, then, you know, put the blame on us. Currently the blame is being put on us anyway, so let us make some of those decisions and let us have some of that power. Let us have responsibility.

In terms of different words like reckoning, reconciliation, recognition, I don’t want to get caught up in too much of that: we’ve never compromised to the point where we say that our sovereignty…has been ceded. It’s just reality that there are things that need to be settled in this country and I guess that is the definition of reckoning. I’ve spoken a lot about coming together to address issues that we need to resolve, about having that two-way dialogue. Getting to the point where we can feel peace. That doesn’t come without justice and it takes a lot of work to get to that point. I identify with the idea of reckoning because I don’t want to hear about who is going to be consulted next or what First Nations perspectives are…and then have no action taken.

Something that Aunty Pat [Anderson] talks about is that we haven’t met as a nation. And that sits strongly with me as a young First Nations person. I feel like we’re always catching up. It would be so nice to just sit still and be, you know. At that point, I think reconciliation can happen, but I don’t feel we’re at the point yet where it can.

PD: Semantics will always get us into trouble, I think – and we’ve got to be clear about what we are aiming at. We saw Gough’s ideological belief in self-determination manipulated and watered down to a concept of self-management. The words might be somewhat similar but self-determination is quite a different concept.

There’s got to be a day of reckoning; there’s no doubt about that. There will be many days of reckoning in a truth-telling process. When we face the truth of all our behaviours in this country – and our own individual behaviours within the country – that’s a day of reckoning. I like the concept of reckoning because you’ve got to get a culmination point. Reconciliation becomes a bit of a process word that seems to go on and on and on. No one really gets to a terminus and we’re constantly seeking to be reconciled. In fact, we’ve made some real key changes to the way we behave towards each other – you could say they’re part of the reconciliation process and part of the recognition.

Recognition in the Constitution isn’t simply the summation of the recognition people want. It’s a Western way of acknowledging that you’re here within the constitutional framework of this nation. But it doesn’t make you into anything better than who you are at the moment.

These words needs to be unpacked: we’ve got to find the basis for the processes that have been enunciated by the Uluru Statement. The process to get the Voice will be a referendum, so what’s the set of words we want to put in the Constitution? Let’s start debating whether they’re suitable or not – let’s have a discussion about that. The question of the Makarrata Commission – Victoria has done something like that; not too many other states have. The Commonwealth has certainly been shying away from it and a treaty-making process.

We’ve got to grapple with the component parts and the establishment of these things as much as what we might end up with or what they might achieve. And be realistic about how long some of these things do take. I’m not advocating delay, but there is a combination to process: what you’re trying to get recognition about or reconciliation about or reckoning about. All of those things are important, but fundamentally there’s got to be a change. And the kind of change is as critical as the way we go about working for the change.

When Gough came in and said, ‘We’re not going to delay any longer; we’re going to get down and do it,’ it didn’t auger well for him and his party. But he set a very, very important foundation that is very hard to undo now. We need the leadership and that sort of courage at the federal political level; we almost had it with Keating but that dissipated with arguments that arose out of the Wik judgement and the power of the mining industry and others that came to play. The complexity of our civil society requires us to be adroit and astute about how we go forward around complicated sensitive issues. But don’t shy away from them and, if you get the opportunity, push them forward.

BC: A lot of our Elders are still doing the work, they’re still there and they’re still fighting. The love that they have for us younger ones and future generations to come – they do the work because of us. And that’s pretty clearly [put] in the Uluru Statement. I’ve heard stories from people who were at those dialogues who say that was always at the forefront of the conversation: what is the legacy we leave for our young ones and their futures?

It’s just so generous for people to not think about themselves, the struggles that they’re going through, the things that they have to deal with on a daily basis, [but to have] big-picture thinking: what is the structural and systemic change that needs to happen here? These aren’t people with university degrees or anything like that. These are just intelligent people who want the best for everybody and for everyone to have the same opportunities and for justice to be achieved.

PD: We learn a heck of a lot from those around us, those who inspire us; we can learn from history by reading about others who we’ve never known or we admire, like Mandela or Ho Chi Minh or Malcolm X or Martin Luther King Jnr. The breadth of challenge to deal with matters of injustice can be informed in many, many ways by leaders in all sorts of places. I think the foundations of our social and cultural drivers are tremendously important: for me, the land has always been a very strong motivator – this terrible thing called terra nullius told us we didn’t belong in this land. We knew that was a lie well before the High Court told us it was. So the land and the connection to the land – not just the physical earth, the topography; it’s the spirituality that comes from there and the connection to the laws that arise from the land. That shows the generation that I come from.

A lot of the younger people are growing up in the cities in towns or away, disconnected from land. They might have the opportunity from time to time to go back and visit and I hope they do because there’s something about the land that drives us politically as much as it helps soothe the anger and the frustration that arises because of the ignorance you confront in trying to create the space that generosity could occupy. Having touchstones of your cultural basis and your foundations, that’s as important as reliance upon older people.

For me the most important legacy of the Whitlam government in terms of reconciliation, recognition, reckoning is the land rights legislation – Gough didn’t enact it, but he set it up. He acknowledged the significance of land and the significance of sites. He obviously understood the integral connection of Aboriginal people to their lands in the symbolic way that he poured the soil of this country into Vincent’s hand at Daguragu, rather than the other way around. The other matter is the opening up of international observation of us as a nation. There are standards internationally that may wax and wane from time to time but it’s important that we look for standards that have some international credibility when it comes to First Nations affairs and their rights and interests in this nation.

BC: I think about the actions Whitlam took in his three years. First of all, to do the work. To understand, to talk to people, to listen, to be brave and to take those steps that need to be taken – that we as Australians all know need to be taken. And to be honest with doing that. One thing that comes through a lot of the things Whitlam did in government was making sure that all Australians have access to fairness and equity – that’s the most important for me. I wouldn’t have a lot of opportunities had those things not been set up during the Whitlam government. Like you said, Senator Dodson, they might need to be reignited a little bit – but they have been put there and there’s an opportunity to make more of them.

This is the second conversation in a collaborative series designed and curated by Griffith Review with support from the Whitlam Institute.

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

About the author

Bridget Cama

Bridget Cama is a Wiradjuri Pasifika Fijian woman and Co-Chair of the Uluru Youth Dialogue. She has worked closely with the Uluru Statement from...

More from this edition

Writing back

MemoirSIR SAMUEL GRIFFITH was my great-great grandfather. He was one of the ‘founding fathers’ of Australian Federation, a premier of Queensland, the first Chief...

Glitter & gold

PoetryListen to Sachém Parkin-Owens read his poem ‘Glitter & gold’ accompanied by world-renowned beatboxer Tom Thumb. We need action Not condolences Far too long we marched, danced and died Screamed, starved and...

But we already had a treaty!

Essay IN JULY 2019, the Queensland Government launched a series of community consultations as part of its Path to Treaty initiative. The then Department of...