Featured in

- Published 20110607

- ISBN: 9781921758218

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THE MONSTROUS WAVE that engulfed the north-east coast of Japan, sweeping the means and products of decades of industrial production and centuries of cultural and social life into its evil black waters, was a terrifying and heartbreaking reminder of proportion. Even the most careful planning and extensive warning systems, produced by one of the richest and most ingenious peoples on earth, were as naught when confronted with nature’s full fury.

Coming after months of increasingly intense floods, cyclones, fires and earthquakes around the world, each described by those most affected as ‘really surreal’, the Japanese tsunami and its after effects demonstrated that reality can be infinitely scarier than any Hollywood special effects studio can conjure: real and surreal (in the sense of happening on a screen) at the same time.

There was nothing abstract or make-believe about the devastation, as the before and after images of towns and cities up and down the Japanese coast demonstrated. While the scale may not have equalled the earthquake in Haiti, or the tsunami in Indonesia and Sri Lanka, that Japan – which only a month before slipped from second- to third-richest country in the world – could be revealed to be so vulnerable added to the shock.

The Japanese have done more than their share of heavy lifting in taming wicked problems and grappling with exquisite dilemmas. It is particularly poignant that a country which has suffered more than any other from the impact of nuclear weapons should have come to rely so heavily on atomic power and again confront the apocalyptic edge of its capacity.

While attention has shifted to China and India in recent years, for many decades Japan was a global inspiration, building a new future from the rubble of war, finding a way to maintain cultural traditions alongside modernist global production and edgy cultural expression.

But after the wave hit, pushing over barriers, roads, bridges, houses, schools and factories, racing up valleys at the tail end of its extraordinarily swift journey across the ocean, it was clear that a new generation of problem-solving geniuses would be needed to pluck hope from the debris. And in the context of the times, this will demand a new style of leadership to that of their grandparents, not least because of information. In the immediate aftermath of the nuclear crisis the suspicion that authorities were being less than frank compounded people’s anxiety.

NEVER BEFORE HAS there been so much information about looming and current disasters, and never before have people expected and demanded to be kept so informed. Rather than triggering a retreat, this seems to be encouraging activism – and the expectation of a different form of leadership, one that engages transparently and openly. It is a test of leadership that the Queensland Premier, New Zealand Prime Minister and the mayors of Brisbane and Christchurch passed.

Premier Anna Bligh set the bar high by the way she managed the cascade of disasters that inundated her state. Her direct and calm communication of the details of what was happening, what was likely to occur, and the recommended ways of responding to the floods and cyclones, ensured people had confidence that they were being treated as adults, being given the information they needed to make informed decisions and react accordingly.

This undoubtedly contributed to one of the most striking reactions to the natural disasters that befell the region early in 2011: the almost entirely spontaneous organisation of community support.

The response to the floods in South East Queensland was different to that of thirty-seven years ago, when people retreated and complained that ‘the guvn’mnt ortta’ sort out the mess. This time the much-criticised ‘Gen Ys and Xs’ stepped in and responded to the directness of the Premier’s message and the immediacy of the threat. They used the networks they have created, the social media tools at their disposal, and the muscles and energy of youth to help clean up. Within thirty-six hours Volunteers Queensland took 60,000 calls from people offering to help – most of them aged under forty.

A similar pattern occurred in Christchurch, where young people were at the fore; students from the local universities applied their brains and brawn to helping make life bearable after the horrifying earthquake. At the time of writing it was too early to know whether the pattern would repeat in Japan – even if the information blockages of the first few days did not clear, my hunch is that the pattern will repeat. This is a highly connected and engaged cohort.

In all these emergencies there were sporadic stories of looters and low-lifes taking advantage of the vulnerable, but this was spectacularly outweighed by the preponderance of people responding with generosity and humanity.

The baby boomers had been told that there was no such thing as society, and that self-interest would always prevail. And while many were sceptical about these messages, for decades in the West it was the orthodoxy. Yet, when confronted with extraordinary disasters, their well-educated children – who have collectively witnessed more surreal disasters than any other group in history, as worlds repeatedly collapsed, collided and imploded on screen – demonstrated the fallacy of both theories. They were highly connected to their local and virtual communities, and drew a link between self-interest and collective interest. Clearly for them there is such a thing as society, and they want to help shape it.

THIS IS A sentiment neither confined to natural disasters nor to Australasia. Well-educated young men and women were at the forefront of the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, and on the receiving end of the bullets and rockets in Libya and Bahrain. Night after night they appeared on television, arguing in perfect English for the democratic and civil rights the rest of us have long taken for granted. The ability to network facilitated by social media played its part, but as a tool, not a proxy for action.

The importance of the information in the secret US cables revealed by WikiLeaks must not be underestimated in unleashing this process, for good and ill. It is a new phenomenon: never before have people known so much about the behind-the-scenes opinions and decisions that shape events. The cables demonstrated that the political corruption in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and others was not a figment of the imagination or merely the personal experience of disgruntled individuals, but an assessment shared by well-informed diplomats who had been trained to make judgements.

As US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton observed with some pride last December, soon after the US diplomatic cables were published: ‘What you see are diplomats doing the work of diplomacy: reporting and analysing and providing information, solving problems, worrying about big, complex challenges. In a way it should be reassuring, despite the occasional titbit that is pulled out and unfortunately blown up.’

In a world where journalists are regularly expelled (or worse) from countries for gathering such observations and reporting them, the insight from the US cables was invaluable – they pointed to essential truths that can often not be said out loud. In the tumultuous months that followed, the WikiLeaked cables helped make sense of the extraordinary events in North Africa.

Again, information was the key, despite all the noisy outrage about threats to life and limb, and the angry accusations of treason against Assange. Of the 250,000 cables only 24,000 were classified secret or not to be read by foreigners, and the rest were merely ‘confidential’. The release of the information could be classified as an exquisite dilemma – who is opposed to freedom of speech and inside information? – but the lack of security of the cables, allowing them to be leaked, pointed to a systemic, if not wicked, problem.

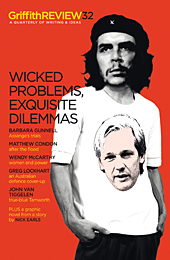

IF THE TIMES produce the leaders and icons they need, Julian Assange is surely an embodiment of his generation. Flawed, obsessive, brilliant, he is the product of his time and place and the tools at his disposal. He has, with customary grandiosity, promised that his book will be a manifesto for a generation.

Just as the baby boomers reacted against their parents and at the same time were a product of their parents’ (especially their mothers’) longing, ambition and hope for a different world, so their children are responding to contradictory signals absorbed when young.

The more I read and heard about Julian Assange, the more I was reminded of the kids with sleep-matted hair and runny noses who sat silently in the living rooms of the 1970s and early 1980s, listening to the faux-revolutionary talk of their (often stoned) parents. Peter Carey created a portrait of such a child in His Illegal Self (Viking, 2008). In this novel, drawn from Carey’s experience in the hippy communes of the Sunshine Coast and from the story of the revolutionary American Weathermen, the boy Che floats on the wave of his parents’ dreams and fantasies as he struggles to make sense of an environment that is chaotic, paranoid and replete with danger.

While the parents of Che and many children like him gradually jettisoned their youthful dreams and obsessions, the values that originally motivated them endured and have found expression in their children.

It is easy to forget how our world has changed since 1971, when Julian Assange was born. As the celebrations of a century of International Women’s Day reminded us, the equality and openness, standards of living and education of today were once unimaginable, are without parallel in history. Remarkably, this transformation has been achieved incrementally, without chaos and, despite an at times rancorous public domain, without major disruption. Change is a non-negotiable part of life, sometimes within our control, but often not.

WHEN WE BEGAN commissioning for this edition of Griffith REVIEW, in October last year, the aim was to explore a series of wicked problems that resist simple linear solutions, the big, complex issues that morph into their unintended consequences. We wanted to examine some exquisite dilemmas, when dreams were almost, but not quite, realised. We also planned to explore the possibilities of design-led thinking to produce new innovative, resilient and exciting solutions. The events of the past six months messily intruded, but the prism of the wicked problem remained relevant. In this world the most complicated human problems are nothing compared to the power of nature. That in itself is both a wicked problem and an exquisite dilemma.

17 March 2011

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

Vanellinae

PoetryAnd I know now, about the birds – their Latin name, theirpopulation and international distribution. I know their migratory patterns and have watched footage of...

Dying, laughing

FictionKYLIE THOMAS'S CHILDREN had been on the roof since early morning. She had heard them, vaguely, tapping at the edges of her consciousness, as...

Learning from Norway

EssayAUSTRALIANS ARE USED to comparing their country with the United States and their countries of origin, whether the UK, Italy, China or any of...