Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Is poetry disabled?

In poetry’s capacity to self-define, to reject conventionality, to be in a constant state of flux and to hold the contradictory together in its granularity, it subverts formal systems of designation time and again. Poetry then avoids simple diagnosis, at least pre-emptively.

More from this edition

To sing, to say

Non-fictionHow poetry works – its oracular way, its indirection – is how land works, he saw. Land as a teacher, as an embodiment not only of its own intergrity but of human aspirations and virtues like hope and beauty; land as an educator of the senses; land as a measure against which to prove and compare one’s own and others’ lives, as a theatre for the divine comedy of all human life; land as an elder, as a god, as a library...

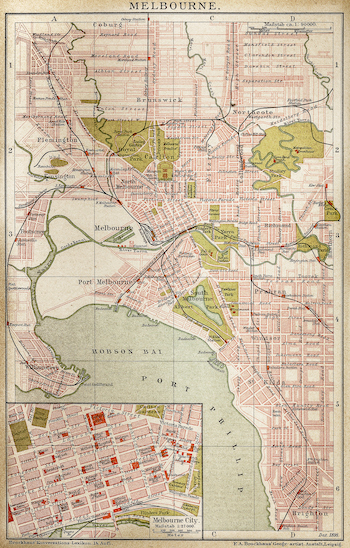

The dancing ground

Non-fictionAfter some initial research, and only finding one historical reference to a ceremonial ground within the CBD, I confined the puzzle of Russell’s lacuna to the back of my mind. The single reference I found was in Bill Gammage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth, where he writes: ‘A dance ground lay in or near dense forest east of Swanston Street and south of Bourke Street.’ Not a great lead because it was two blocks away from where it was depicted on Robert Russell’s survey.

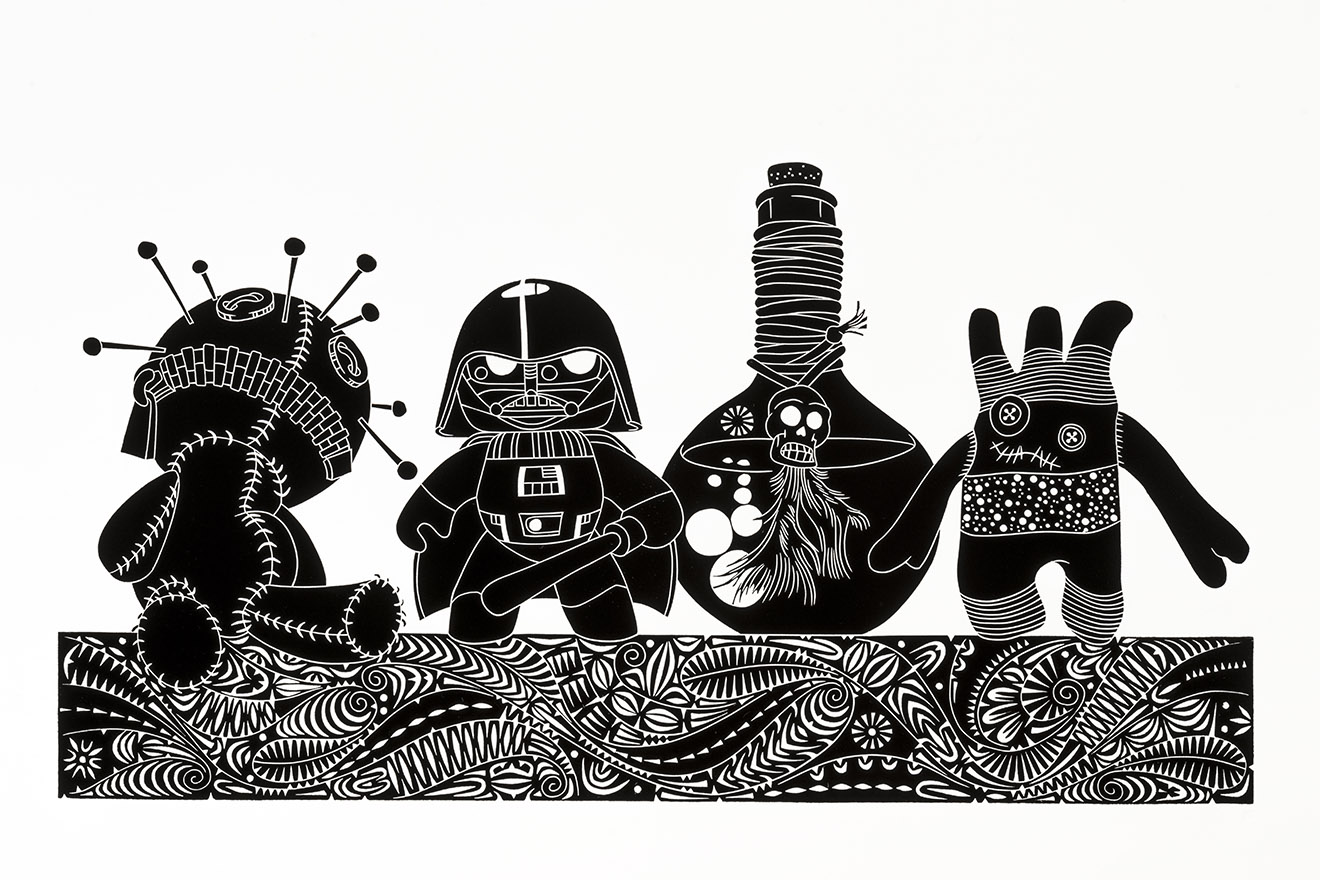

Pop mythology

In ConversationEven though I grew up on a small, remote island, I was still heavily influenced by television – particularly the sort of cartoons that would play on Saturday mornings, mornings before school, after school and so on. When it comes to DC and Marvel and all of those superheroes, for me that was ignited by my late grandfather Ali Drummond, my mother’s father, who had boxes of Phantom comics. Phantom was my early introduction to the strong, powerful male being who had supernatural strength and abilities.