Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Glitter and guts

All those years I had been excluded from the Anzac narrative because the Defence Act had outlawed Black enlistment. Lest we forget morphs into satire when you uncover the depths of collective amnesia surrounding Black service in World War I and Black resistance since colonisation. The more accurate catchphrase would be Best we forget. How can we be ‘one’ when we are not allowed to remember equally? Nostalgia is selective about remembrance.

More from this edition

The dancing ground

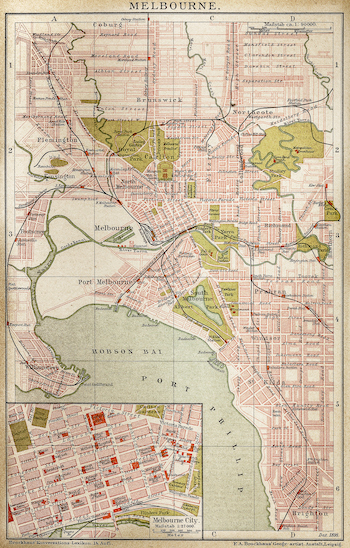

Non-fictionAfter some initial research, and only finding one historical reference to a ceremonial ground within the CBD, I confined the puzzle of Russell’s lacuna to the back of my mind. The single reference I found was in Bill Gammage’s book The Biggest Estate on Earth, where he writes: ‘A dance ground lay in or near dense forest east of Swanston Street and south of Bourke Street.’ Not a great lead because it was two blocks away from where it was depicted on Robert Russell’s survey.

Let there be light

IntroductionWhether they’re personal, cultural or religious, these are the stories that offer us ways of orienting ourselves amid the sheer chaos and confusion of being alive – particularly today, as humanity’s existential and environmental crises continue to mount.

Autumn

PoetryTsunami-hit, shoved over at a tilt, they’ve left the bashed old kovil’s god-thronged tower standing, tallish, beyond the new one built to face, this time, becalm, the ocean’s power…