Featured in

- Published 20060905

- ISBN: 9780733319389

- Extent: 288 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

I’M CELEBRATING MY mother. Pink tissue paper and ribbon fold and tie over the gift: foot lotion. Lavender scented. A present for the Mother’s Day I usually forget. The last few years have been celebrated with a phone call in the late afternoon, just scraping in. Though now I’ve felt the pain, I know the sleeplessness, the sacrifice – even though I’m only four months into it.

Someone passed comment the other day: “Hunger makes the best sauce.” I liked the sound of that. It made me think of my mother: she did the best she could, and what she could do – was the best.

I’M DOWN THE side of the house smoking a cigarette. I don’t want anyone to know, so I’m crouched by the edge of the outside wall, by mint and dripping tap. The clothes line spins my daughter’s nappies in the twilight. I blow the smoke in the other direction. It feels good, all my frustration silting out into the air. The river drinks the last slip of pink before night. I wish I could run to the river and swim downstream instead of up. Up here on the hill where now, inside, my baby girl cries to be held, to be fed, to be changed, to be bathed and to be rocked back to sleep. There’s no one else to do it, and I’ve stopped considering that if I leave her for a while she’ll forget about me. We cannot forget our mothers.

My mother had me when she was twenty-one; I turned twenty-two a couple of weeks before Lila arrived. My mother is non-Aboriginal; it is from my father that I get the olive in my skin and it is out of my father’s shame that I get his pride.

I’m proud to be Aboriginal. My father wasn’t allowed to be Aboriginal. He was best to swat away their questions about his physical appearance with something vague – “that’s the wog in me brother”. My father worked the taxi cabs; he’d bring home the lingo, chasing us around the house with his belt – “Get here ya bloody Gesepe – gunna clip ya round the ear hole”, that sort of thing. But quietly, just to us kids, he’d tell us not to let them other kids call us coons. We had a little Aboriginal flag in the dining room to look at. When I was arrested a few years ago, I was wearing a polka dot red halter-top with a flag just the same stitched on to the front. I’ve always been proud to be Aboriginal.

The girls at school would sunbake at the beach in the afternoons and all day on Saturday and Sunday. I’d join them after a surf; I thought my skin needed to be darker. No one wanted to believe I was Aboriginal. No one still wants to believe I’m Aboriginal. The word “descent” is better fitted, half-Aboriginal, a quarter of Aborigine from my father, a little bit in the teeth, the ankles the dark brown eyes. A little bit of heritage from a mob that was supposed to be wiped out, and they wonder why my skin is light brown. Not brown. Not black.

I COOK ON Wednesdays at Young Mothers Group. We’re all Koori girls, most in dire situations, in our teens or not far off. Some girls are in emergency housing with a couple of kids, some still at home – hoping to go back to school soon and catch up. I haven’t got a car and I live in the bush so I get picked up by one of the health workers. The other week she glanced at me in the rear-view mirror.

“So, what’s the writing about anyway, Sis?”

“About growing up with light skin in an Aboriginal family, not really belonging.”

“That’s different, eh? I wanted to kill myself over my skin – I would never go in the sun, I was scared to get blacker. Always thought … that’d be alright, being light-skinned. Then I had this Chinese lover, he loved my skin, and he wanted me blacker. Made me feel sexy being black.”

I could feel her words. They cut just above the surface, a paper cut. The words were my imaginings that are real because the rest of society makes them real. What kind of fuckin’ bleeding heart bullshit is that! Fuckin’ poor little light-skinned girl!

But she turned to me as we pulled up at the lights.

“Good on you girl. We’re so proud of you.”

I READ SOMETHING that someone had written about me. It went along the lines “of Aboriginal heritage … Single. 22-year-old. Mother. On the pension. A criminal record.” That’s my box. I’ve come to accept it and, although my mates know me as Tara and someone who’s always up for a laugh, Centrelink, the Department of Housing and the system in general know me as something else, a few boxes that allow lips to be pursed as I push the pram to Woolies.

There’s another group of people: they’re not the system and they’re not my mates. They are the others. The others so badly want me in those boxes but only to turn me around on the stereotype and parade me as their product, out of the adversity of a box I have risen.

I hate this. I’m their non-stereotype stereotype. At least the computer fits me into their box, and that’s that. I’m ticked “yes”. And there are no grey areas. But the others like to scratch at the grey, brush it away. Make it lighter. Make it darker.

I feel pulled. I wish the moon governed the world and our bodies could be colourless.

MY FATHER LIKES his coffee strong and with lots of sugar. The doctors are always warning him about his blood sugar.

“Gotta have a guilty pleasure,” my father argues. “Anyway, sick of people talking about my blood.”

Blood too sweet, too this, blood too black, blood too that.

I suppose my father has experienced being neither black nor white. I suppose my mother will never understand that part of him, and that part of me, and that part of my daughter. That race – and particularly colour – both segregate and unite. And my bloodline is washed in white. That this is a broken link. That my father cannot be proud because he doesn’t know what to be proud of – that he is Aboriginal or that he is a fair-skinned Aboriginal.

I wonder, if I had dark skin, would I feel the same? Would I be pushed into a shame mindset? Is it only because I can move within the white society unnoticed that I feel so strongly about my Aboriginality? That I need to tell people I’m Aboriginal or they wouldn’t know. That first I am recognised as being one of their own, before being recognised as the other?

I USED TO feel really angry. I was arrested for assaulting a police officer on the night of finishing an essay I’d written about Australia’s racist history. We’re warned at the beginning of our Indigenous Studies units that the content may be traumatic to some people. I’d only read about it and I felt sick. A book, maybe merely a passage, had turned me to feeling so overwhelmed with anger and disgust that I lashed out at the closest authority. It had been an exchange between the pages and me. I had not been slaughtered or maimed, nor had my children taken from me. I had not been called a number, been raped, not experienced being beaten because of my colour.

What right do I have to be Aboriginal?

I cannot speak on behalf of my mother or father. I can only speak on behalf of me. But I feel as if there is no one who wants to hear. Maybe I feel like I have nothing to say. I’m branded as an “Indigenous Author”. This does two things: it first puts anything I write in the Australiana section of major bookstores, with maps and books on bushrangers. I’m not a real author – I’m a token author. I’m a souvenir.

The other thing it does is cause an argument – am I only allowed to write about black issues? Or, because I also celebrate my mother’s skin and blood, can I not write about that lineage? Or am I even allowed to write about the experience of being Aboriginal, since I’ve got fair skin? WHAT DO THEY EXPECT ME TO WRITE ABOUT? What dance would you like me to do?

SOME OF OUR babies at young mothers group have white skin. Some of them have skin darker then their mothers’. We don’t see the babies’ fathers. We match our babies’ sizes and smiles and big eyes. Us girls all laugh at the different cries, like little lambs we say. We say things like this one’s gunna break hearts when she’s older. This one is too cheeky for his own good. This one’s got those puppy eyes, gunna get away with murder.

We never say it but our babies will be different. Our babies are mixed blood; they’ll be misinterpreted and maybe teased like us. They’ll be branded as too white or too black. We never say things like that, Even though we know them. We’re all from broken links. Our babies suffer the past too.

Happy Mother’s Day. I scrawl across the card that I thank her for giving birth to me and for being so supportive of who I am. My mother always trusted us, knew that we’d pull through, knew we’d find our feet, our hearts, our identity. Knew we’d always come back to where we’re from. That we are from our mother and our father – that maybe we have his eyes and maybe her hair. That we’re from both bloodlines. And we wouldn’t be ourselves if we were different. My mother called us by our Christian names, my father was called by a slang nickname, and my grandmother was a number.

I wonder who we are, these white blacks, these black whites? These half-coloured people? What do I want to say? Maybe that only I know what it’s like being me. And maybe I’m not alone.

Share article

More from author

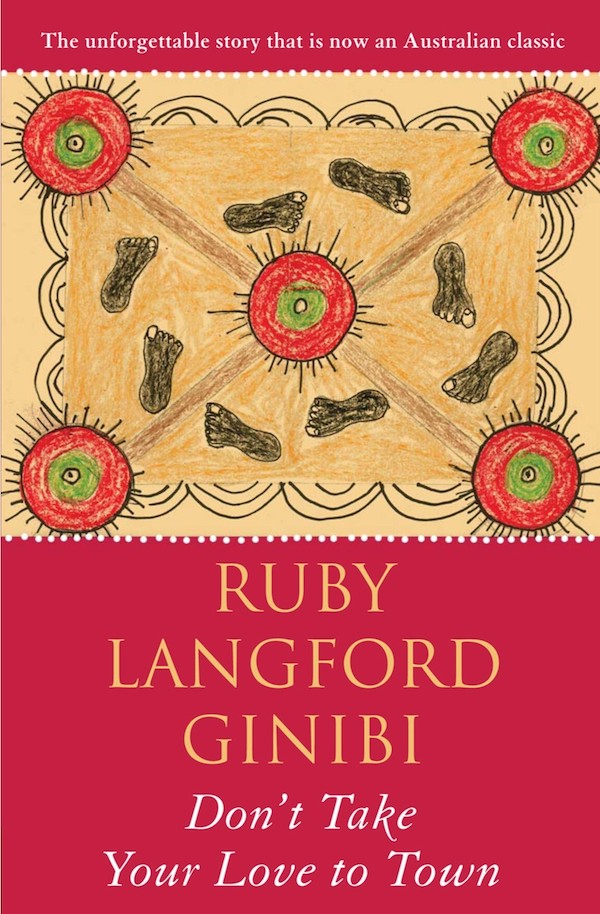

On ‘Don’t Take Your Love to Town’, by Ruby Langford Ginibi

N 1988, DON’T Take Your Love to Town became the first of five autobiographies that Ruby Langford Ginibi would have published during her almost thirty-year career as a writer, Aboriginal historian, activist and lecturer. Indeed it was this first book, her life story covering five generations of familial bonds, written in what would become her trademark conversational style, which would have a historic impression on Indigenous literature in Australia.

More from this edition

Is your history my history?

FictionI NEVER MET my grandfather, but we keep his skull on the top shelf of the hutch, behind two Toby mugs, an insulator from...

Emily

FictionSelected for Best Australian Stories 2006IN ORDER TO get my novel published, I told book publishers Allen & Unwin that I was the reincarnation...

Indelible ink

FictionSelected for Best Australian Stories 2006SHE WAS FIFTY-NINE, rich, divorced for a year, and out alone on a Saturday night. She told the taxi...