Featured in

- Published 20150505

- ISBN: 9781922182807

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

IT SEEMS POIGNANTLY appropriate that the web address gallipoli.net.au, which features the logo ‘Gallipoli: The Making of a Nation’, is owned by Michael Erdeljac of the Splitters Creek Historical Group. Splitters Creek is now a suburb on the western edge of Albury, better known for its active Landcare group, and as the home to the endangered squirrel glider. In the competitive market for Great War memorabilia, Michael Erdeljac deserves to be congratulated. He has owned the URL for fourteen years – well before commemoration became a national preoccupation – motivated by his own conviction ‘we must remember’.

The history recalled on the site is serviceable, the list of names of those killed at the Gallipoli landing, Lone Pine and Nek battles heartbreaking, the opportunity to ‘own a piece of history’ well priced: $1,200 for a framed print of a photo from the front. The photo was donated by the late daughter of Corporal Herbert Bensch, one of the many Australians of German heritage who fought for the AIF in the Great War. It was in a camera belonging to his mate, who was one of the nearly nine thousand Australian soldiers, three thousand New Zealanders, thirty-five thousand Brits, twenty-seven thousand French and eighty-six thousand Turks, who died on the peninsula a century ago. Years after returning, Corporal Bensch processed the photo and it became a family heirloom.

It is poignant because it was settlements like Splitters Creek in the Riverina that were home to many of the almost sixty thousand Australians who died during that war. As has been graphically captured on the screen, and is now easily accessible in the digital records of those who fought, many of the young men who volunteered to travel across hemispheres were country lads woefully ill-prepared for the slaughter they would face. Not all, like Corporal Bensch, traced their forebears back to England. For many of those who fought it was a chance to be involved in a great adventure, albeit often with tragic consequences.

THE NOTION THAT this blooding and the other epic battles of the Great War made Australia a nation has become a truism, but it is one that needs to be examined.

Australia was already a (teenage) nation in 1914. It was a nation crafted from and for the times, eager to assert its independence (in most things) from the motherland, infected by a racism made (almost) scientific by Darwinism, egalitarian, protectionist and, in important democratic domains, marked by a progressive spirit. In many ways it was a world leader – forging both a civic and an ethnic idea of nation.

In Europe, by contrast, at the beginning of the war, as David Reynolds details in The Long Shadow (Norton, 2014), there were only three republics – France, Switzerland and Portugal – but five major empires: the Ottoman and British, and those headed by the Romanovs in Russia, the Austro-Hungarian Habsburgs and the Prussian Hohenzollerns. Five years later, all but one of these empires had imploded – there were thirteen new republics and nine nations that had not even existed before the war.

In Europe, the sixteen million lives lost and twenty million injured literally created nations. The carnage emboldened a democratic, nationalist and in some places revolutionary, spirit. It led to major political changes in Great Britain, the beginning of the end of the old aristocracy, and eventually the devolution of Ireland. In Australia, by contrast, it divided the progressive movement, tingeing the country with grief.

Although the trauma and loss was profound in Britain, Australia and New Zealand, there were no battles on home soil in either the motherland or the dominions. In Britain the outcomes were less concrete – more tied, as Reynolds argues, to ‘abstract ideals such as civilised values and even the eradication of war’. In Australia, as John Hirst has written, ‘Gallipoli freed Australia from the self-doubt about whether it had the mettle to be a proper nation’.

So in Australia, the experience of war became shorthand for nationhood, while in New Zealand it marked the beginning of a long journey to even fuller independence.

It is an ancient notion that equates battle and blood with independence and freedom; that there is life in death. The very idea that war ‘was the truest test of nationhood and that Australia’s official status would not be ratified psychologically until her men had been blooded in war’ is, as historian Carolyn Holbrook persuasively argues in Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography (NewSouth, 2014), evidence of ‘muscular nationalism [that] was given legitimacy by Social Darwinism’.

The Great War did not make Australia – that had been a relatively cerebral activity, notwithstanding the conflicts of settlement, which reached its conclusion on 1 January 1901 when the colonies federated into a nation. It was a nation that began as penal colonies, prosecuted battles of settlement, welcomed people from many lands and crafted one of the first written constitutions. But like many adolescents it was conflicted, as Holbrook argues, ‘the very nation that it sought to distinguish itself from was the nation whose approval it craved’.

The Great War was not even the first foreign war that Australians fought in alongside Britain – that was in South Africa. But as the legend of Breaker Morant has captured, there were important differences in attitude between Australia and Britain that came to the fore in foreign battles. Many historians have argued that the lingering feeling of illegitimacy, of having a chip on the shoulder that needed to be avenged, helped fuel the idea that participation in the Great War was a coming of age – proof, as John Hirst noted in Australian History in 7 Questions (Black Inc., 2014), that Australia really had the ‘mettle to be a nation’.

Eagerness to participate was not universally shared. This is illustrated most powerfully in the failure of two referenda to introduce conscription – another important mark of an independent nation, of a place where people had the right to make their own decisions rather than being the property of the state. So those of Irish heritage expressed anti-British sentiment, those of German descent were regarded suspiciously, and Indigenous Australians joined the fight. It was complicated. Afterwards, the tragedy of loss and grief was palpable and Australia’s progressive spirit was slowed and lost momentum.

And then, in little more than a generation, another war began which layered trauma on catastrophe, left the air full of human smoke, changed global geopolitics and renamed the Great War – World War I. In an enduring sense, it was the Second World War that really changed the world. It consolidated the American Century, defined in part by conflict with the Soviet Union and its empire; triggered the end of colonialism and its multifaceted implications; created space for the assertion of international law; and provided the framework for the remarkable transformations of the past seven decades.

UNDOUBTEDLY, THE WARS of the twentieth century shaped, arguably even made, modern Australia. But this was not because of an ancient blood sacrifice in distant lands or even the closer strategic battles that followed; it was a product of the responses, realignments and decisions that followed.

Every country has its most symbolic year from each of the world wars, and can trace the consequences of the bloodletting that accompanied the global realignment of the last century. In Australia this can be measured in many ways, but three major legacies stand out: increasing independence from Britain, deeper engagement with the rest of the world and more multiculturalism at home. It was in the aftermath of these wars that Australia found its voice in international forums – at Versailles and in the formation of both the League of Nations and United Nations. After excluding the Chinese, deporting German residents and treating the first Australians as subhuman a century ago, Australia slowly let down the gangplank and after the Second World War began again to welcome large numbers of people from all around the world. While full legal separation from Britain took much longer to achieve – and is still a work in progress – the reaction to the knighting of Prince Philip on Australia Day 2015 suggests this is a project nearing completion. At a more prosaic level, one of the greatest media empires the world has ever known can trace its antecedents to the wartime reporting (and political deal making) of Sir Keith Murdoch.

As Jenny Hocking documents in Enduring Legacies, it was the wartime experiences of Gough Whitlam that shaped his political agenda that was implemented three decades later, and still upholds the foundations of contemporary Australia.

IT IS STRIKING that 2015 is the centenary of the Gallipoli offensive, the seventieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in the Pacific, and the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. This is a good time to reflect not only on the actions of those wars, but on their consequences and their enduring legacies. The battles are important, but the lessons to be learnt in their aftermath need to be interrogated, to explain how we got to where we are.

This is essentially an intellectual exercise, and Australians generally shy away from such activity, preferring celebration, commemoration and consumption. This year is replete with travel agents offering guided journeys to far away battle sites (because, apart from Darwin, none of these modern wars occurred on mainland Australian soil), books, films, television series, exhibitions and coins.

The ballot for places to attend the Gallipoli Commemoration was massively oversubscribed and the Perth Mint’s 99.9 per cent gold ‘Baptism of Fire’ $5,050 coin sold out quickly, but there are still plenty of the 99.9 per cent silver ‘Making of a Nation’ coins for just $99 and others with similarly overblown names. The first episode of Channel Nine’s magnificent Gallipoli series attracted millions of viewers before sinking into ratings netherland. And the Splitters Creek Historical Group still has copies of Corporal Herbert Bensch’s colleague’s battlefront photo and the list of many of those who died at Gallipoli a hundred years ago.

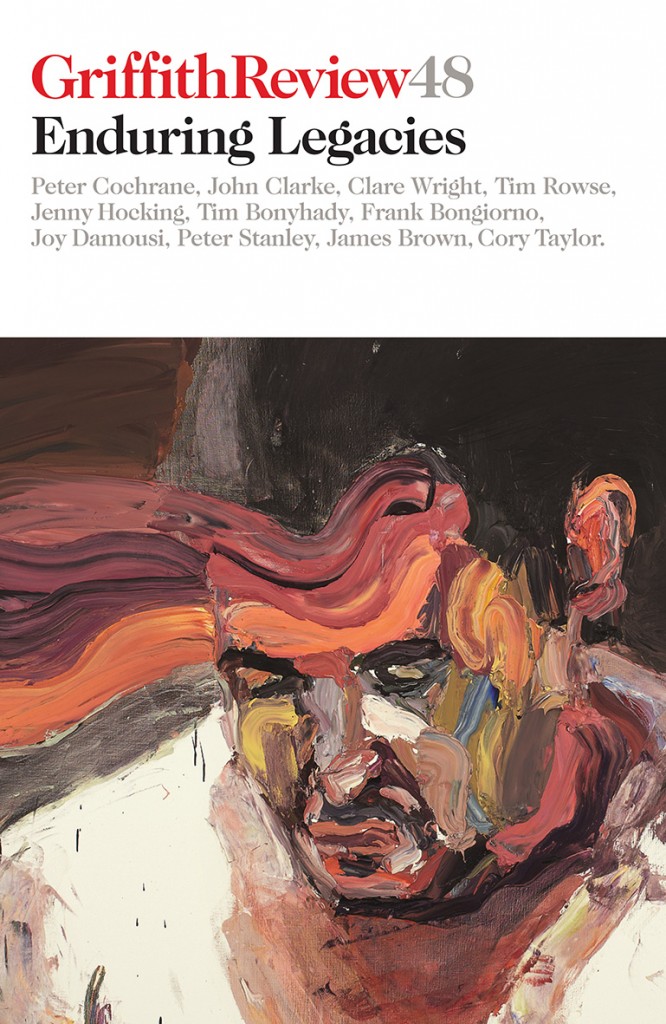

IT HAS BEEN a great pleasure and privilege to work with my colleague Dr Peter Cochrane on this edition of Griffith Review. Peter’s network of eminent historians have risen to the challenge of exploring many of the multifaceted legacies of the wars of the twentieth century – and have provided new insights, graphic portraits and telling analysis of their consequences. We have chosen to organise the edition chronologically, so it starts with the Second Boer War and ends with a haunting reminiscence about the seventy-fifth anniversary of Kristallnacht. In between, we address most of the wars of the twentieth century, as well as the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with new insights, poignant tales and surprises. It is the beginning of a much bigger project to explore the enduring legacies of wars in shaping who we are, and why.

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

A Christmas story

MemoirJUST AFTER MIDNIGHT, six soldiers were shot in their beds in the Officers’ Quarters on Christmas Island. Their bodies were wrapped in bed sheets...

Dangers and revelations

EssayFOR INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS, experience of the Second World War went beyond service in combat roles. Consider the Davis brothers in Western Australia: as Jack...

A remarkable man

MemoirRAY PARKIN TOLD stories. He wasn’t exactly the Ancient Mariner, but there was an insistence and a very steady eye about the way he...