Featured in

- Published 20130305

- ISBN: 9781922079961

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

EVEN BEFORE THE fires, the hectic summer season had its first tragic trial. In early December, my husband Nick flew to London to be with his mother whom he loves and who is dying, presenting me with the challenge of running our accommodation business, Bicheno Hideaway, throughout Christmas alone. Four cabins and the boathouse set on four hectares of foreshore bushland overlooking red lichen-covered rocks and the ocean.

A spontaneous decision we made ten years ago to exchange our Paddington terrace in Sydney for a life on Tasmania’s east coast.

Not so much a sea-change experience as becoming bit-part players in the equivalent of The Shipping News. Nick is a jeweller and I am a writer. From galleries in Sydney, Melbourne and London, the local post office now represents Nick’s art pieces. After winning the 2001 Commonwealth Writers Prize in the South Pacific Region for my debut, The Company, my novels are available from the newsagent. We are happy, we have moved on.

In Nick’s absence I was doing quite well completing fairly scary tasks such as moving hundreds of litres of water from one tank to another without losing a drop.

Then on Christmas Eve, our close friend and neighbour, Bicheno’s beloved doctor, died suddenly at his home. The funeral took place on 3 January, with the community in deep mourning. That night I sat on our deck mesmerised by a massive electric storm, lightning flashing and forking and striking the ocean and for a brief moment a light patter of rain, the first in weeks.

The following day turned out the hottest on record, forty-three degrees. By late afternoon as I was watering our shrivelled orchard, fruit dropping from the trees, a cloud mushroomed from nowhere, rising and billowing. About time, I thought, showers at last. Although when I glanced up, I could tell by the sulphur underbelly, its orange tinge, that I was seeing a vast sheet of swiftly moving smoke. I hurried down to the rocks where my group booking from the Boathouse had gathered.

They were return guests, locals from Burnie, and, like most Tasmanians, expert readers of the wind and the sky, the rips and the tides. ‘She’s blowing southwest, she’ll be all right,’ they said.

Although I have lived in Australia for twenty years, I find information of this kind invariably impressive, reducing me to my original Pom status accustomed only to weather patterns of ceaseless rain. Mightily relieved I left them to continue their walk and set to watering the scorched vegetable garden. Part of Hideaway’s charm, I thought, its main attraction lies in its dense natural bush setting, home to a variety of birds and wildlife which guests find delightful and makes the property entirely indefensible in the event of fire.

Two hours later, the Boat House party started packing their car.

‘I am sure things will be fine,’ they said. ‘Did I mind if they left a day early?’

‘Not at all,’ I replied.

Greeting the arrival of two couples in Chalet Four, I was told that Silver Sands Motel had vacancies in town.

‘Best to be safe,’ I said as they too drove off. Knowing that alternative accommodation was now available, I checked with Silver Sands and decided that my other group booking in the other chalets should also head for the sanctuary of Bicheno. Sensibly they agreed.

ALONE AND WITH no guests to worry about, I began to fill containers of water and distribute pellets and grain among my flock of bantam chooks, my ever-expanding mob of semi-tame wallabies, headed by the matriarch, hand-raised orphan Lucy, now eight years old, my peacock and his hens and two-day-old peachicks, five in all. At this point I felt quite calm, the spirals of smoke evident but seemingly abating, when the telephone rang, my agent, which was surprising as we had not talked in a while. I had been enjoying the freedom of reading and weeding with no thought of writing following the publication of three novels, a loose trilogy each with a shipwreck disaster acting as a catalyst to the central narrative. My agent said she was concerned, having heard a news bulletin that bushfires were raging along Harveys Farm Road.

I should have been alarmed at this. Instead I reassured her that I had evacuated the guests, and now had time to see to the animals.

There was a pause followed by a long sigh.

I remembered it had also been a while since we had spoken the same language.

‘This has been the worst year for Australian publishing,’ she declared. ‘I have a first-time author, terrific deal with Text yet –’

At this moment, a policeman appeared.

‘I’d better go,’ I said.

Quickly he explained: situation completely out of control, at the signal of the sirens get to the water as fast as you can.

‘When might that be?’ I asked.

He looked at me and shrugged.

‘How long is a piece of string?’

I raced to our house on the block adjacent to Hideaway. Our blue tin house, the ceiling lined with Tassie oak beams, the wide timber decking, our home, which Nick built sturdy as a ship.

In the course of my novels, there have been situations similar to this, when the survivors of the wreck snatch their possessions in a mad scramble to escape the stricken vessel.

What to take, what to leave behind?

The artwork we have collected over the years, sensational canvases, the oil portraits of my mother when she was young, wearing a turbaned Moroccan hat? The china? Nick’s scrimshaw? My passport? Locked in the safe, but where is the key?

I grabbed a shopping bag and tore upstairs. In the end a useless kit, pretty frock, best shoes, my blood pressure machine, phone charger and a bottle of white wine. By now the wind had picked up, I was sweating and the heat was intense. Is it possible for our house to spontaneously combust, I thought, as I ran out the door and made for the rocks as fast as I could? I heard the sirens.

It is one thing to sit on a bench on flat rocks and admire moonrises and migrating whales and another to jump from boulder to boulder and reach the water’s edge slippery with kelp. I managed to perch on a crag, black wavelets slapping at my boots. And then the front came through, volcanic lava blazing towards Freycinet National Park. I could describe the unearthly flash and flare, the crackling streaks of madder rose, siennas and deep ochres, but most vivid in my mind is the tumult and speed of the storm’s roar, the heat on my face, as eucalypt and bracken were swallowed and no more.

Nick called from London at his usual hour. I told him where I was.

‘Not to worry,’ I shouted above the gales and the thunder of that sinister force out there.

‘I’ll be on the next plane,’ he said.

Despite the inferno raging the skies, night began to fall. It occurred to me that of all basic essentials, the one item I lacked was a torch.

How stupid was that?

I SEEMED TO be taking a long time to catch up with myself since sighting that first giant cloud. Crouched alone, I suddenly felt truly afraid. I could trip over and injure myself, fracture a bone and be of no help to anyone if they found me instead of battling the fire. In the half-light, while I could still discern the outlines of the rocks, I should carefully retrace my steps and seek refuge in Chalet Two, which although backing onto a forest of gum overlooked a cleared aspect of lawn and a quick exit to the water. Strange to shower in the bathroom I had scoured that morning and even stranger to lie in the bed I had made so competently as well. I poured a glass of wine but passed on a blood pressure check. I tried to sleep. When eventually I sank into oblivion, I woke to a frantic pounding on my door and voices shouting ‘Get out, get out.’

I joined the residents of Harveys Farm Road at the bakery. My neighbour on the other side had elected to defend his home but his companion had ridden her Arab stallion bareback through the smoke and the ash to the safety of town. I made my way to a friend’s house at the Blow Hole and watched the hill burn with the TV turned up high. Advice gave way to alert and catastrophic. I thought of my lovely peacock, flames torching his fabulous train, the peachicks sheltering beneath their mother’s down, my wallabies, with their slender black paws, bolting through the undergrowth, and I felt ashamed of myself.

We realised that the community on the other side of the hill, Half Moon Bay, had become engulfed. People we knew had lost their homes. I could not believe this was happening to us. The hours dragged on. We watched the ruins of Dunalley and received a text message declaring the fires would rip through Bicheno in thirty minutes, but that turned out to be a false alarm.

Zoe, Nick’s daughter, called to say he was already on a plane.

By mid-afternoon, my other neighbour Monique burst in.

‘I’m defying the police blockade,’ she announced. ‘I’ve got to get to the horses.’ She nodded my way, ‘you’d better come with me and make sure your animals are all right.’

The smoking land was eerily silent. I opened the shed door and reeled from the heat. I filled a bucket of water and threw pellets around our house where the wallabies graze. Lucy came bounding towards me, and her great extended family waited in the shadows. Lucy jumped away and then came bouncing back, time and time again. I rushed over to my bantams, still there, still scratching the dust. And weaving through the haze came the peahen and her five chicks. The peacock shrieked and shrieked from his perch in the carport.

I dumped piles of feed not just for my animals but for any injured creature that might still be alive. Monique came to fetch me and we returned to the limbo of the Blow Hole.

Later I heard that Harveys Farm Road was open to residents only so I decided to stay once again in Chalet Two, not trusting the thickly forested foreshore in front of our house. The bantams had roosted in the coop, and with a certain amount of misgiving, I shut them inside.

All night the hillside rumbled with the growl of bulldozers, helicopters overhead, the fire fighters tirelessly manoeuvring the back burn with a brave and ruthless military precision.

THE FOLLOWING MORNING I woke to the phone ringing. An ABC crew wanted to come round. I assumed it was the radio, wore my same old clothes, no time to shower. I let out the bantams. Fed them and the peachicks. The ABC arrived. To my horror they dragged a camera out of their vehicle. I followed them into the Boathouse, like me the place was a mess, and onto the deck. Throughout the interview, I realised I had been shoehorned into an angle, namely that Harveys Farm Road had been saved. Nick called from Sydney about to board a connecting flight. He had been studying the weather on the Internet. Seventy km/h winds were forecast for Tuesday, which might fuel the fires back onto Bicheno.

That morning, my guests returned from Silver Sands in high spirits. The ABC crew filmed them against a backdrop of smoke wreathing the hill.

Now, one week later, it is business as usual, the hillside bright, the air clear. The fire fighters had worked day and night to save our homes.

My peacock displays in a patch of sunlight, stamping his feet and fanning his feathers putting on quite a show for a group ready with their cameras.

Share article

About the author

Arabella Edge

Arabella Edge read English Literature at Bristol University and came out to Australia in 1992. She is the author of three works of historical...

More from this edition

Obstacles to progress

EssayFOR MOST TASMANIANS a darker reality lies behind the seductive tourism brochures showcasing the state's pristine wilderness, gourmet-magazine articles celebrating its burgeoning food culture, and newspaper stories gasping at a world-leading art museum.

Oscillating wildly

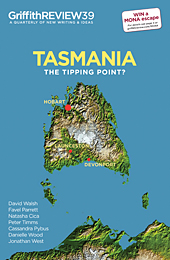

IntroductionTASMANIA OCCUPIES A unique place in the national imagination. It is different in so many ways to the vast, dry expanses of the continent...

The island of broken dreams

GR OnlineTASMANIA IS VIEWED by many Australians who don't live on the island as some kind of paradise. The traffic is slower and there is...