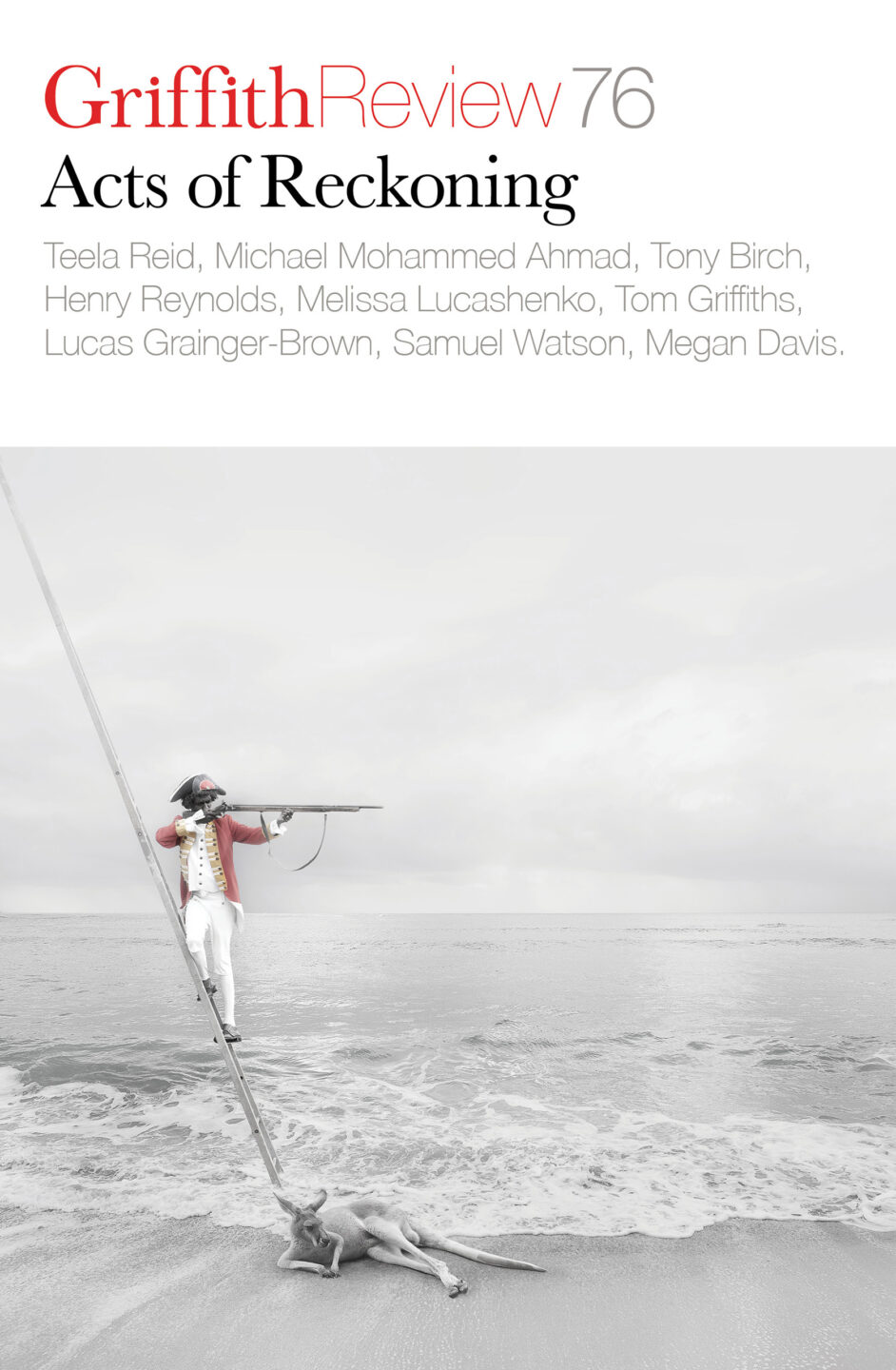

Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Mykaela Saunders

Mykaela Saunders is an award-winning Koori and Lebanese writer, teacher and community researcher and the editor of This All Come Back Now (2022), the...

More from this edition

Dune coons and crescent moons

MemoirFIRST WORDS Kes emak. Your mum’s cunt. Don’t judge. I learn them from my mother. She is at Coles in Redfern, and I am nestled in...

Disrupting the colonial narrative

Essay The many Indigenous nations of the globe have always been storytellers, and our stories tell of an animate reality in which everything lives and...

Radical hope in the face of dehumanisation

In ConversationOur Elders are the epitome of these thousands of generations of existence and survival in this place, and if we’re thinking about the future of the world and our survival, we need to be learning from these people. They hold the most knowledge, the most intimate knowledge of not just surviving but of thriving and maintaining generosity in the face of all the challenges.