Decolonising the shelf

A special series in celebration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages

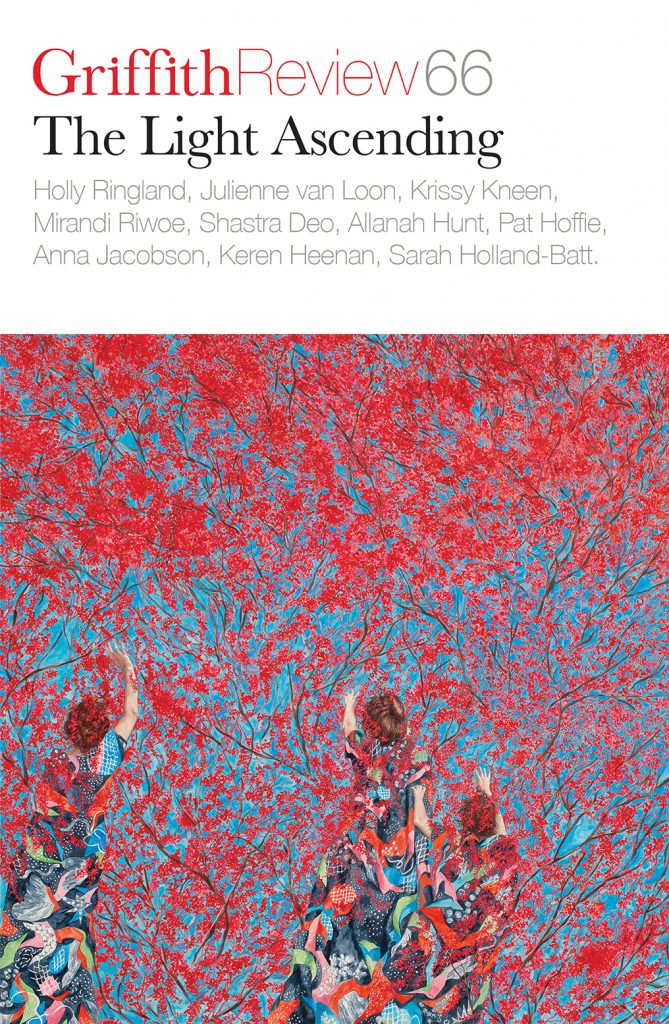

Featured in

- Published 20191105

- ISBN: 9781925773804

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

To acknowledge and celebrate the International Year of Indigenous Languages, I set myself a goal to read only Indigenous authors’ works in 2019. I’ve partnered with publishers to receive their books by Indigenous authors – historical and contemporary, in mother tongue and English – and will be sharing my reviews of these works online for Griffith Review over the next few weeks. To understand the power and complexity of First Nations writing and writers today, it is essential to look at where we’ve come from and those early writers who still inform our writing today.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this essay contains the names of people who are deceased.

IN AUGUST THIS year, I was speaking at the Canberra Writers Festival when I was asked a question during the audience Q&A. The woman was baffled – she wanted to know why she was only now discovering so many First Nations writers. She wanted to know, in her words, ‘why the explosion, what has changed?’

I answered intuitively, a little hurried for time. I said that, contrary to any sense of great change or explosion, we are a culture that has survived by storytelling; we have a long history of writing, and we’ve continued to write and publish. It wasn’t us who changed, I said; it was her. The collective readers of Australia had finally recognised their national identity crisis and responded in turn.

I don’t know if this was entirely correct. I’ve noticed the times as much as she has. I’ve realised that readers are embracing our stories as their own. In the past few years, I’ve seen anthologies of First Nations’ writing published, the presence of our books in top-ten and prize listings – and, of course, I’ve noticed festival audiences for events featuring First Nations writers increase in numbers, in openness and in the questions they ask.

I thought about this woman later and wondered: have I been paying attention fully? I want to look closely at who we are now, where we’ve come from, where we’re heading. I want to look at our writing, our languages and our wider story to try to understand it all myself. To celebrate that great canon so many people never knew or still don’t know, the books that us contemporary First Nations writers carry on our backs – just as we carry the past, and our ancestors’ stories too. 2019 is the United Nations International Year of Indigenous Languages, the year that celebrates and promotes protecting the 2,680 native languages around the world that are in danger of being lost. Our languages are essential to our unique cultural and historical identities and traditions, and to navigating our future autonomy, human-rights protection, peace-building environmental care, reconciliation and reparation, and sustainable development. This year in particular is important for looking at how our publishing industry has and is playing a role in that celebration and promotion of our oldest stories, our original storytellers and the first languages of this country.

BEFORE THE COLONISATION of Australia, 600 language groups comprised the oldest surviving civilisation on earth. Inseparable from these languages are their stories: they decode not only the rules of linguistic order, but the skies and seas and landmasses and family relations and how the world itself came to be. Locked in languages are hundreds of physical places that a speaker may never even visit. Languages themselves are navigation manuals for living in this part of the world.

In 2019, with around sixty surviving languages and increasing awareness of language importance as a living artefact, there has been a renaissance in Indigenous language reclamation and learning in Australia. Just as school programs are being developed to support maintaining and using Indigenous languages, so too are some publishing houses releasing books written in Indigenous languages. If we know that culturally and linguistically responsive pedagogy contributes to academic success and sound mental health, do we also now grasp the ways our stories contribute to a more understanding and inclusive society?

I think we are beginning to.

We need to break the default of our reading habits to hear stories about ourselves as Australians. We are not only blue yonder and hard yakka; life is lived beyond the nuclear homestead. We are migrant and refugee, gay and trans, city dwelling and still incarcerated. We are millions of voices – and we are, in particular, the original Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages of this continent. We are tongues before David Unaipon wrote Hungarrda in 1927 and Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines thereafter. We are stories that not only run across the entire country, but have appeared in many other cultures, just as the story of the Seven Sisters is alive in the Pleiades constellation of Taurus on this side of the world as much as it was alive in ancient Greek mythology. We are contemporary storylines that cross old missions, towns and cities too, now narrating for us that terrible inheritance with as much literary heft as the best stories have.

On the whole, we’ve been publishing in assimilated language in postcolonial Australia. Our writers were required to use that vehicle of expression to transmit their experience. Now, I want to look at how we can break – and have already been breaking – the mould of English with new works published bilingually. These seem like radical acts, yet with so many of our people speaking English as a second, third, fourth or fifth language in this country, perhaps it’s actually a startlingly reasonable thing.

IN 2008, ANITA Heiss and Peter Minter published the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Aboriginal Literature (Allen & Unwin). I hope they publish another soon. The anthology ran from the English language writings of David Unaipon to my own first book, Swallow the Air, published by UQP in 2006.

It was, will always be, a great honour to be included in that anthology, but we need to revisit its project again. So much has happened in just over a decade. In this series of essays, I hope I can shine a light on our oldest stories and our current custodians, our most recent groundbreaking works and others that are still on the horizon. I hope I can explore our remote stories and our urban dreamings. And through this, I want to answer that woman in the audience in Canberra, tell her about the novels and the non-fiction, the poetry, the children’s books and young adult novels that are there for her to read. I want to look at publishing trends and houses, and towards the future classics we’ll all be reading – the bestsellers, no doubt – in the years to come.

I’d like to show you our ancestors, too, those who first wore down the road we all traverse, from the recently departed matriarch of the First Nations Australia Writers’ Network, Kerry-Reed Gilbert, to William Russell ‘Werriberrie’, King Billy of Appin – who penned My Recollections in 1914 and inserted a dictionary of his own in the appendix – and on to Melissa Lukashenko, recently awarded the nation’s highest literary honour with this year’s Miles Franklin Award. I want to explore how the very act of writing all these stories has sustained us and given all readers, all Australians new and old, a historical record of the life and times of an entire nation. How we aren’t to be missed, not anymore.

We have so much to tell you.

Here is our story, the one we carry on our backs with every book we publish, every day and night: the history that never has and never will escape us.

We are your original storytellers. Our culture has survived through story and we are the civilisation with songlines etched in the land you inhabit.

A week after that festival in Canberra, I heard the great writer Tony Birch speak in Melbourne. He said, ‘When white people write about Indigenous people, afterwards they can walk away. For us it’s a lived experience. With that comes responsibility and accountability.’

This is the history and the story of our accountability and responsibility. It’s yours to read too; yours to be responsible and accountable to. I invite you to decolonise your shelf.

Share article

More from author

For the love of our children

I think that as a nation, Australia has an opportunity to embrace the mother tongues of where we live, whether by supporting local language centres or lobbying for First Nations language programs to be taught in local schools and as part of early-childhood curriculums. This will allow us all to feel a sense of belonging in relation to our cultural history as a nation…

More from this edition

Spectrums

FictionElsie THERE IS LIGHTNESS and darkness. Everyone knows that. There is a name for the shade that is neither light nor dark: grey. But there...

Instructions for a steep decline

FictionWhatever happens, this is. Adrienne Rich ONE IT IS PEAK hour in the City of Light. A woman cycles backwards up a steep incline. The woman...

Cape York

PoetryWhen you arrive at the tip of the Cape, the coast opens its arms and you’re split into the rivulets left by an outgoing tide, your...