Featured in

- Published 20170207

- ISBN: 9781925498295

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THE REFORM CLUB, the imposing Palazzo-style structure on Pall Mall, one of London’s grandest thoroughfares, has entered the popular imagination as the quintessential gentleman’s club. Its camera-ready elegance – the soaring atrium, sweeping staircases and cosy parlours – has given the private club an unusually public life.

As in so many clubs, the portraits and busts of its founders and luminaries are on proud display. The men featured in the pictures were less the stuffy embodiment of the class-bound status quo; they were men with a vision. In many ways they changed the nature of Britain and the shape of an empire. They were principal architects of the 1832 Reform Bill, the pragmatic British response to the French Revolution, which became the first step towards universal suffrage.

Two years later, many of these men were in the House of Commons when the legislation that would transform ‘waste and unoccupied Lands which are supposed to be fit for Colonization’ into a model colony was passed. Within another two years South Australia was proclaimed in seaside Glenelg, a colony based on a thoroughly modern mix of commerce and ethical values: financed by land sales, without slaves or convicts, where the rights of ‘Aboriginal Natives’ to occupy their land was enshrined along with religious freedom, the separation of church and state, franchise, access to education and other social innovations.

In May 1837, a committee of twelve gathered to assign names to the streets and squares mapped out in Colonel Light’s plan for Adelaide, and the link to the Reform Club became tangible in the city’s CBD. Thanks to decades of research by Dr Jeff Nicholas, collected in his three-volume opus The Streets of Adelaide (Torrens Press, 2016), we now know that the names of thirty-five of the thirty-seven streets selected that day were members of the Reform Club.

For anyone with even a fleeting knowledge of Adelaide, it is a disorientating experience to see the embodiment of a city in the refined marble surrounds of a Pall Mall club. Within a decade, South Australia was welcoming not just free settlers from the British Isles seeking a freer and more prosperous future, but Germans seeking religious and political freedom – and it was taking the commitment to respect the rights of ‘Aboriginal Natives’ seriously. The Reform Club origins explain a lot about Australia’s most unusual state; it helped shape a very different colony. South Australia has long been comfortable at the cutting edge of social, economic and political innovation.

MICHAEL O’LOUGHLIN IS one of the great Aussie Rules footballers, a talented young man who moved from Adelaide to become a star with the Sydney Swans. Although he missed his family when he moved east, it took some time, and participation in the SBS series Who Do You Think You Are?, to discover the richness of his connections to South Australia. His family had played a unique role connecting Indigenous and settler societies.

Kudnarto, Michael O’Loughlin’s maternal forebear, was from the Clare Valley. In 1848, at just sixteen, she married Thomas Adams, a shepherd who had emigrated four years earlier. Theirs was described in the South Australian Register as the ‘first lawful marriage to a European’, and the evidence suggests it was a love match. Not long afterwards, Mrs Mary Ann Adams was given a grant of land – one of the forty-two sections that the settlers had allotted to the ‘Aboriginal Natives’. The grant at Skillogalee Creek was ‘for the term of her natural life’, which tragically ended just seven years later in 1855 – and with it the promise that the land would pass to her sons when they reached adulthood.

Two decades on, by the time her son Tom was old enough to resume the land, the policy had changed. In response to a letter Tom wrote asserting his rights and pleading for his land, the Protector of Aborigines in 1875 said he could ‘find no legal authority to give land to an Aborigine’ – and so the costly legacy of dispossession extracted its toll on Michael O’Loughlin’s mother’s family.

Accompanied by the SBS producers, O’Loughlin travelled east to the Coorong in search of his paternal ancestors, and discovered the rich history of his great-grandfather’s legacy. Millerum was a leader in the Ngarrindjeri nation, a man who made his way in the settler world while remaining committed to preserving culture and language. He was the closest associate of Norman Tindale, who devoted his life to mapping and documenting Indigenous clans, country and culture.

The images of O’Loughlin in the Coorong, listening to the recordings of his great grandfather singing and of him in Adelaide meeting Tindale’s now elderly daughter Beryl, who considered Millerum her grandfather, are among the most powerful moments television could deliver. A tearful O’Loughlin promised to continue the family tradition to ‘show the way, share culture and tell stories’.

THE HOPE THAT shaped South Australia has not evaporated, but it has been tested by the harsh realities of an unlikely settlement. The early promise of the Reform Club visionaries delivered a rich legacy, including female franchise and progressive innovations, but at times it also fostered inward-looking complacency and provoked a conservative backlash. Within two decades the recognition of Aboriginal land rights evaporated; within several generations, the towns named by German settlers were Anglicised and many of their descendants interned, and a place defined by the separation of church and state became known as the City of Churches. These legacies still linger. Yet over 180 years of settlement, new visions have, with surprising regularity, become reality, as new people and ideas take root and old initiatives are revived. If a place can have hope in its DNA, it is in South Australia, where it will be an essential ingredient to make sense of the challenges of a new epoch.

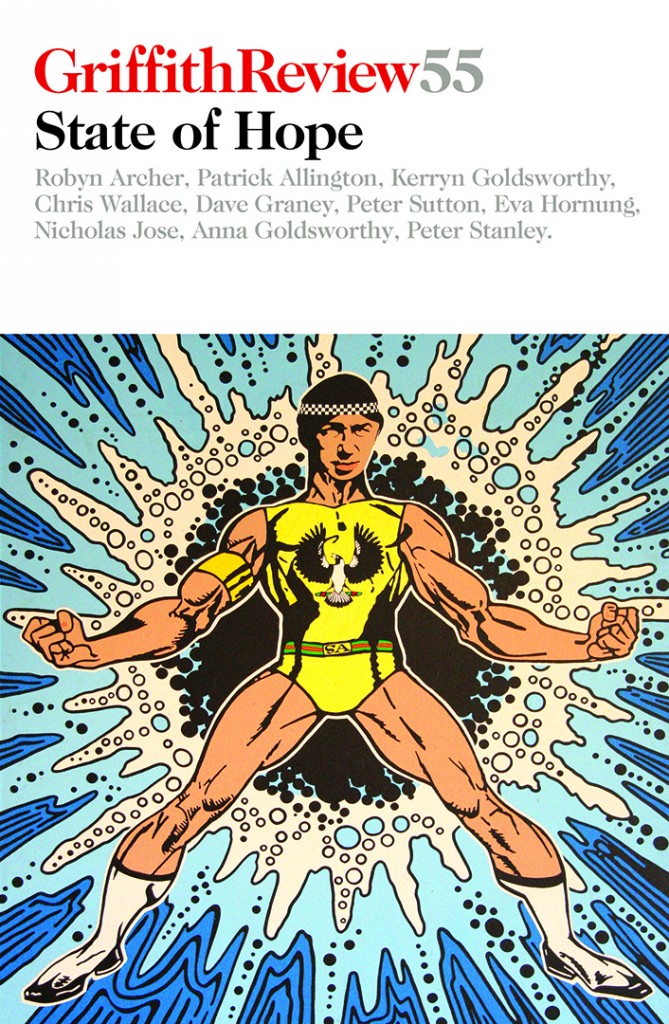

THIS EDITION OF Griffith Review has been produced with the support of Flinders University and Arts SA. It features South Australian writers, and those with a legacy of association with the state. Co-editor Dr Patrick Allington has been a pleasure to work with – he is a gifted and knowledgeable writer and editor with deep insights into South Australia – and his colleague Professor Julian Meyrick a wise and generous collaborator.

25 November 2016

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

Dunstan, Christies and me

MemoirADELAIDE’S GOLDEN AGE began when the Beatles flew into town on 12 June 1964, electrifying the citizenry out of their country--town torpor into a...

Radical roots in Fiji

EssaySOUTH AUSTRALIA’S REPUTATION for progressive reform extends back to its origins in Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s scheme for imperial systematic colonisation. Wakefield’s grand plans, which...

Behind every story

EssayIT MAY NOT be the best painting in the Art Gallery of South Australia, and it may not be the most valuable. But one...