Featured in

- Published 20241105

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-01-2

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook, PDF

I CAME OF age in the 1990s, a period in which it was deeply uncool to believe in anything unless you were being ironic. We’d reached, supposedly, the end of history, and apathy was easy: many of us in the West remember the final decade of the twentieth century as one marked by relative political and social stability. Religious faith also seemed to play an ever-diminishing role in our lives – in Australia, the number of people who identified as having no religion grew by nearly 5 per cent in just five years (1991–96).

Just a couple of decades later, we might say that the unbelief tide has turned. (So much for the end of history.) While society is becoming increasingly secular, our concomitant atomisation and diminishing lack of faith in, and support for, institutions have led us to what historian Anton Jäger describes as an age of hyper-politics: a kind of upside-down version of the ’90s in which everything, from personal social media platforms to corporate messaging, is expected to reflect a particular set of social and political beliefs and values. Yet without the infrastructure to support these ideologies – the unions, churches and civic organisations that once formed the bedrock of our communities – it can feel as though our faith has nowhere to go.

If that sounds bleak, it doesn’t have to be. In his 2016 book But What If We’re Wrong, cultural critic Chuck Klosterman reminds us that ‘any present-tense version of the world is unstable. What we currently consider to be true – both objectively and subjectively – is habitually provisional.’ What we believe in may shift, even as belief itself endures – and both those facets of the human experience can help us learn from the past as we head towards an unpredictable future.

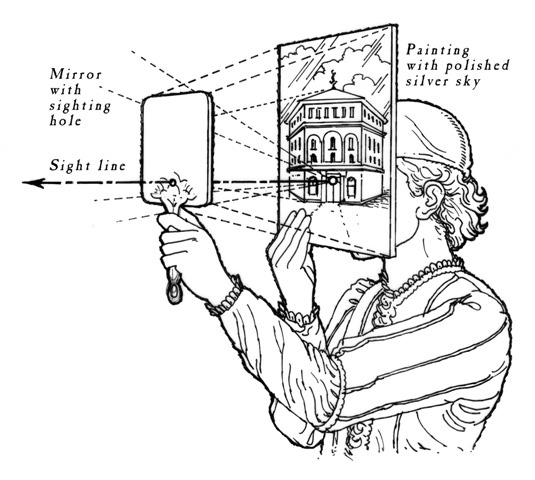

IN THIS SPIRIT of inquiry, the eighty-sixth edition of Griffith Review explores the concept of faith in many different forms and contexts: religious, cultural, emotional and social. You’ll find essays on the power of curses and the allure of magical thinking; on the challenges to our belief in Earth exceptionalism; on the machinations of Australia’s far-right Christian lobby; on the intrinsic role religion plays in identity and anti-colonial struggle; on our misguided attempts to forge a perfect future; on the emotional fallout of losing faith; on our circular attempts to define the Anthropocene; on the changing shape of eschatological thought; and much, much more. You’ll read fiction and poetry that parse the limits and possibilities of our belief in cultural narratives, creative legacies and family ties. You’ll discover conversations about what comedy and good-faith disagreement can offer us and how photography can blur the boundary between fact and fiction. This edition is a typically expansive collection of perspectives and insights, and I hope it reinforces the importance of our faith in literary and intellectual culture and the ways it can help us see and understand the world through different lenses.

With its focus on big questions of knowledge, conviction and existence, this edition feels like a fitting way to cap off another excellent year of Griffith Review. It’s been a less successful twelve months for the world, at least thus far – but I’m trying to believe it’ll get better. As the late, great George Michael (an icon of the ’80 and ’90s whose work transcends both musical eras) once sang, you gotta have faith.

August 2024

Image credit: Brunelleschi’s Rediscovery of Linear Perspective. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Share article

More from author

The art of appropriation

I had this assignment at university when I was doing my creative arts degree. A lot of the time, art students will copy the old masters to get better at painting and fix their technique. So I thought, I’m going to give this a go and copy Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus – and while I’m at it, I’m just going to make Venus brown and make her look like someone I know. I didn’t really have words at the time to say why I was doing that – I was just drawn to it.

More from this edition

Feeling our way to utopia

Non-fiction JANE AUSTEN WAS just twenty-one years old when she wrote her first novel, Sense and Sensibility. Today, we understand her works as more than...

Moonshot

Poetry in the tenth set he sent the tennis ball on an interstellar galaxy quest, a sudden outburst which seemingly served no visible purpose but still remained an...

On the contrary

In Conversation Australian novelist Lexi Freiman knows how to walk a literary tightrope. Her fiction is both savagely funny and strikingly empathetic, daring to satirise the...