Featured in

- Published 20241105

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-01-2

- Extent: 196 pp

- Paperback, ebook, PDF

I CAME OF age in the 1990s, a period in which it was deeply uncool to believe in anything unless you were being ironic. We’d reached, supposedly, the end of history, and apathy was easy: many of us in the West remember the final decade of the twentieth century as one marked by relative political and social stability. Religious faith also seemed to play an ever-diminishing role in our lives – in Australia, the number of people who identified as having no religion grew by nearly 5 per cent in just five years (1991–96).

Just a couple of decades later, we might say that the unbelief tide has turned. (So much for the end of history.) While society is becoming increasingly secular, our concomitant atomisation and diminishing lack of faith in, and support for, institutions have led us to what historian Anton Jäger describes as an age of hyper-politics: a kind of upside-down version of the ’90s in which everything, from personal social media platforms to corporate messaging, is expected to reflect a particular set of social and political beliefs and values. Yet without the infrastructure to support these ideologies – the unions, churches and civic organisations that once formed the bedrock of our communities – it can feel as though our faith has nowhere to go.

If that sounds bleak, it doesn’t have to be. In his 2016 book But What If We’re Wrong, cultural critic Chuck Klosterman reminds us that ‘any present-tense version of the world is unstable. What we currently consider to be true – both objectively and subjectively – is habitually provisional.’ What we believe in may shift, even as belief itself endures – and both those facets of the human experience can help us learn from the past as we head towards an unpredictable future.

IN THIS SPIRIT of inquiry, the eighty-sixth edition of Griffith Review explores the concept of faith in many different forms and contexts: religious, cultural, emotional and social. You’ll find essays on the power of curses and the allure of magical thinking; on the challenges to our belief in Earth exceptionalism; on the machinations of Australia’s far-right Christian lobby; on the intrinsic role religion plays in identity and anti-colonial struggle; on our misguided attempts to forge a perfect future; on the emotional fallout of losing faith; on our circular attempts to define the Anthropocene; on the changing shape of eschatological thought; and much, much more. You’ll read fiction and poetry that parse the limits and possibilities of our belief in cultural narratives, creative legacies and family ties. You’ll discover conversations about what comedy and good-faith disagreement can offer us and how photography can blur the boundary between fact and fiction. This edition is a typically expansive collection of perspectives and insights, and I hope it reinforces the importance of our faith in literary and intellectual culture and the ways it can help us see and understand the world through different lenses.

With its focus on big questions of knowledge, conviction and existence, this edition feels like a fitting way to cap off another excellent year of Griffith Review. It’s been a less successful twelve months for the world, at least thus far – but I’m trying to believe it’ll get better. As the late, great George Michael (an icon of the ’80 and ’90s whose work transcends both musical eras) once sang, you gotta have faith.

August 2024

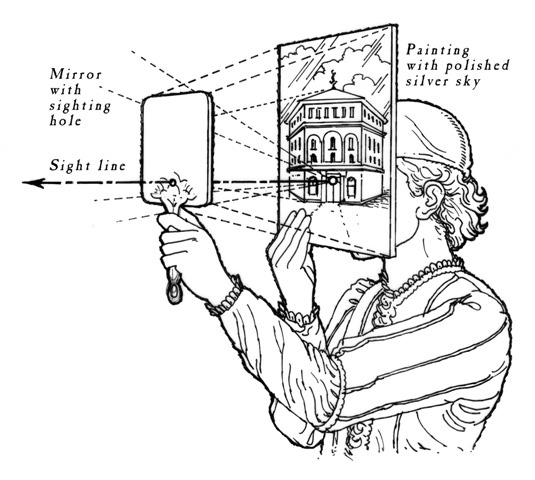

Image credit: Brunelleschi’s Rediscovery of Linear Perspective. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Share article

More from author

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

More from this edition

Up for debate

In ConversationDebate emphasises different ideals. You are forced to argue for positions you don’t believe and, regardless of your stance, you learn always to consider the opposing perspective. That is quite literal: after preparing your case, you turn to a different sheet and write the four best arguments for the other side or mark up your argument for its flaws and inconsistencies. Paper and pen. That is countercultural at a time when we expect a tight nexus between speech and identity, and I think there is something to be gained from such role-play.

Mustard seed

Non-fiction ON SABBATH MORNINGS, I fidgeted as we knelt on the speckled purple carpet. The polished wood of the pews smelt of lacquer in the thick,...

Baba

Poetry A friend suggests a psychologist, but my grandmother was a house witch, her mother the thirteenth child of the thirteenth child. Knock twice on the cards...