Featured in

- Published 20190806

- ISBN: 9781925773798

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THE WAILING

THERE IS A deep wailing across this country. I heard it once when I was a child in Mount Isa. The wailing is a primal sound that goes through your whole body. It’s a communal wailing. As an Aboriginal person, I am very conscious that as a society we have lost much. There is an abyss of sadness too great for us to straddle, like Archie Roach’s haunting song ‘All Men Choose the Path They Walk’.

As a five-year-old child, I felt that immense sense of loss. It was already deep inside my soul. My loss at that age was for my country, K’gari (Fraser Island). I had no words to articulate it, just an intuitive knowing.

Slowly, I began to understand that the Badtjala people had been written out of history. This has been a gradual progression and a continual trait of colonial descendants who, as victors, write history to make sovereign nations invisible. There were no visible traces of my forebears in the landscape. No monuments, no plaques, no streets or buildings named in their honour.

I remember the old people around Urangan when I was growing up. The characters they personified. For the ones already gone, their memory lived on in the retelling of their witty dispositions, infamous exploits and charitable deeds. In particular, I am reminded of Banjo Owens here. As my mother recounts, ‘We used to call him Buthung. He’s of the Owens clan, you know. Well, he was well liked and well respected… We learnt a lot from him.’[i]

But as decades passed, the same occurrences were repeated. Acknowledgements for Badtjala lives are becoming less and less. There is no profile written about my mother, Shirley Foley, for securing leasehold land on Fraser Island in 1990 to establish Thoorgine Education and Culture Centre Aboriginal Corporation. Or her published Badtjala dictionary. She certainly would not be featured on ABC’s Australian Story. In Hervey Bay, all the municipal buildings, parks, streets and Rotary seats are named after white residents, never a Badtjala person. However, my mother did get one suburb there named after our clan: Wondunna. Throughout my life, she was a tireless advocate for Badtjala culture until her passing in 2000. My strength comes from her, an exceptional teacher with staunch morals, a jovial soul who loved life, a visionary who took on an argument, carved a path around a political obstacle and never settled for anything less for her nation. Yet where is her legacy in the visual landscape of K’gari or Hervey Bay? For a lifetime of work to better the Badtjala people, Shirley Foley has been actively and passively written out of history.

I understood from my mother that I too had a cultural responsibility, as a Badtjala person growing up in Queensland and New South Wales, to make a difference, to stand and fight for a principle, and to never back down when Aboriginal culture should be front and centre. The premise of my work has largely been to write Badtjala people or Aboriginal nations back into the visual landscape. Through my many public discourses, I have learned to research and raise an intelligent argument. Australia’s accepted history is now being challenged as Aboriginal scholars from many nations contest those positions of unfounded historical truths.

STUD GINS

THE PERFORMATIVE IN my work has been researched using particular props, costumed people, and themes, and by unpacking vignettes in all manner of mediums: photography, public art commissions, installations and film. A number of my works, such as Stud Gins (2003, in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia), Witnessing to Silence (2004), Bearing Witness (2009), The Oyster Fishermen (2011), Vexed (2013) and Black Velvet (2014), all explore a topic no one wants to talk about – not in Queensland, anyway. That topic is the factual accounts of the actions carried out by Queensland’s white forefathers, who perpetrated sexual and physical violence against Aboriginal men, women and children.

Scattered through the pages of various publications are the state’s foundations: a litany of massacres, kidnappings, rape, bashings, whippings, shootings, stabbings, drownings, burnings and other depravations. Both the film Vexed and the sculpture Black Velvet look at documented sexual violations on the frontier. Germaine Greer states in her book On Rage (MUP, 2008) that ‘in 1900 at Ardock Station in Queensland, nine Aboriginal women were kept in a fenced compound for the use of the white station hands.’[ii]

When I first created an in-depth body of work examining the sexual violence and massacres that took place on the frontier, it was presented to a Brisbane audience in 2003 at Griffith University’s Queensland College of Art (QCA) Dell Gallery.[iii] The exhibition was titled Red Ochre Me, and was opened by the Minister for the Arts at that time, Matt Foley. Stud Gins was in the exhibition and ran the length of one gallery wall – a seven-part blanket installation with seven words: Aboriginal, women, defiled, ravished, shared, discarded and property. One of the blankets has ‘QG’ stamped in the corner – it is an original Queensland Government blanket that could have been handed out to -Aboriginal people after the frontier wars.

I was under the impression that my artworks would trigger much discussion. One review by Shaun Weston states: ‘They shock us because they expose the truth, truths that are largely untold and denied. Truths that most of us weren’t taught about at school…truths we may only come to realise after encountering Foley’s work.’[iv]

I was sadly mistaken. My art elicited the opposite response. I was unaware I had created powerful work that could not be spoken about. On a number of levels, a very public rebuke was issued. I learnt many lessons about Queensland and its representatives that year. I learnt how a society can shun you through absolute silence. I learnt how institutions can do the same. I’d overstepped some invisible mark. As an Aboriginal in Queensland who had largely grown up in Sydney, I didn’t know my place. I was being spoken to through a wall of passive resistance. SILENCE.

From that time on, I knew I had very few allies – somewhat like the days of yore, when, as Henry Reynolds writes in Forgotten War (NewSouth Publishing, 2013): ‘A rigid code of silence would shield both police and settlers.’[v] Played out daily in the fine arts are the machinations of class and race. I was surprised this still remained, an undercurrent from our shared colonial days, an intricate dance of racial politics. Queensland’s colonial hang-ups have over time shaped a society, its attitudes, its actions and its level of engagement with Aboriginal artists.

WITNESSING TO SILENCE

IN THE PUBLIC domain, I have used my research for major public art commissions, such as Black Opium, Sugar Cubes and Witnessing to Silence, on a number of occasions. I was commissioned to create the sculpture Witnessing to Silence outside the Brisbane Magistrates Court in 2004. I pitched the concept as focusing on Queensland bushfires and floods, but all along I intended it to represent our state’s hidden history of Aboriginal massacres.

The question, really, is this: how do you artistically represent a massacre site in the twenty-first century? Do you re-enact the violence all over again, or do you portray it in another way?

I have chosen to convey violence poetically through suggestion and metaphor. As Reynolds and others identify, the evidence in Australia was removed: ‘When the bodies of victims were encountered they were almost universally burnt to destroy the evidence.’[vi] This was a common method adopted across Australia. I have taken the concept of destroying evidence to its bare minimum by using ash as a metaphor for Aboriginal mass killings, or by melting bullet casings and having them cast into the aluminium foundry pour.

My work challenges the status quo and has brought me into direct contact with politicians on more than one occasion. This is evidenced in the article by Miriam Cosic in The Australian in 2005: ‘Rage revealed in urban landscape.’[vii] Once the real meaning behind Witnessing to Silence was made public, the scales of justice tilted in a way that required some official response to the work. Anna Bligh was the Minister for the Arts at the time, and remained positive about the commission for the Brisbane Magistrates Court. However, this project unfolded over two years. The process to get to that point initially involved a meeting with the former Minister for the Arts, Matt Foley; my solicitor became involved on three separate occasions. While I was in the concept-design and design-development phases, a series of meetings took place, one with the then director general of Arts Queensland.

In the International Journal of Cultural and Creative Industries, Jay Younger writes: ‘[Fiona] Foley questioned conservative choices in public art commissioning and the desire for uncritical or harmonious art.’[viii] This is true. However, I did more than question conservative choices – I outmanoeuvred all involved with the commissioning process because they were so caught up in the minutiae of wanting to present palatable art to a general public. The committee was looking for ambiguities in the detail of the concept design when there were none. I presented a generic list of place names in Queensland to the committee and substituted that list with the names of ninety-four massacre sites when it came time to fabricate. I employed a researcher to find for me all the massacre sites she could that were listed on the public record. The place names etched into the pavers for all to see was the manoeuvre no one was expecting.

The Brisbane Magistrates Court or the Department of Justice and Attorney-General would have reconsidered their position on the commissioned work if they knew what I was working on. Queensland, even in the 2000s, was too conservative for such truth-making. For non-Indigenous people, any inclusion of Aboriginal history is subject matter out of their control. Australian society only wants feel-good stories, not the reality of Aboriginal resistance.

Following Anna Bligh’s supportive comments about the work quoted in The Australian, Younger explains, ‘it could be argued that when Foley’s artwork was embraced by Bligh, to some degree it was silenced by the forces of authority that the artist intended to critique’.[ix] This is one hypothesis that does not address the judiciously researched historical evidence. No one from the Queensland Government has ever questioned the list of ninety-four massacres etched into the pavement. At the end of the day, this really isn’t a story about Fiona Foley, Arts Minister Anna Bligh or the Department of Justice and Attorney-General; it is about Australia’s repeated injustices towards Queensland’s Aboriginal nations, the First Peoples of Australia who fought and died defending their land. No court in Queensland has ever made reparations to any of the state’s Aboriginal sovereign nations that it hunted, tortured or killed during the frontier wars. This is the crux of the matter so poignantly represented outside the Brisbane Magistrates Court. Justice: ‘She symbolises the fair and equal administration of the law, without corruption, avarice, prejudice or favour.’[x]

Editor’s note:

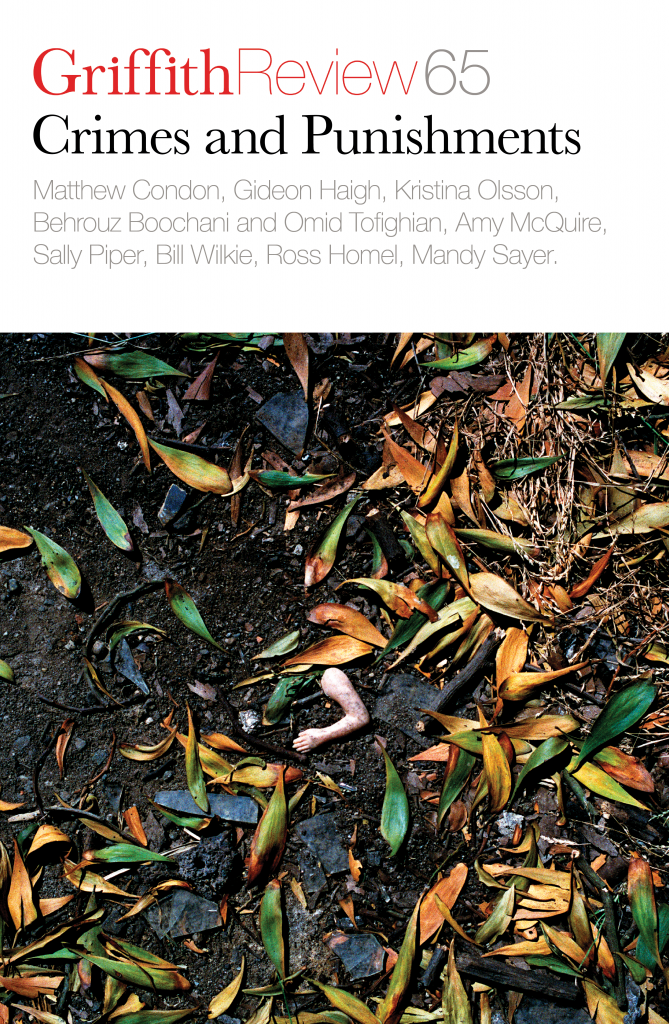

The hard copy and PDF editions of Griffith Review 65: Crimes and Punishments, ‘All men choose the path they walk: Art and the scales of justice’ by Fiona Foley features a selection of the artist’s work.

References

[i] Shirley Foley, The Badtjala People, (Hervey Bay: Thoorgine Educational and Culture Centre Aboriginal Corporation, 1994), 19.

[ii] Germaine Greer, On Rage (Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2008), 47–48.

[iii] Simon Wright was the Griffith Artworks Director who supported my ideas to bring this exhibition to fruition in 2003.

[iv] Shaun Weston, ‘Red Ochre Me: Fiona Foley’, Local Art – Issue 6 (2003): 10–11.

[v] Henry Reynolds, Forgotten War (Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2013), 208.

[vi] Ibid, 123.

[vii] Miriam Cosic, ‘Rage Revealed in Urban Landscape’, The Australian, 10 March 2005, 14.

[viii] Jay Younger, ‘Difference or Dissent? Curating Indigenous Women’s Artwork in Government-commissioned Public Art’, International Journal of Cultural and Creative Industries, Vol 1, Issue 3, July (2014): 81.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] http://itsaboutjustice.com/symbol-justice/

Share article

More from author

Exploding time past and time present

Picture GalleryTHE VERY IDEA of stepping back in time as a Badtjala woman is a utopian thought. Back in time the Badtjala people traversed to...

More from this edition

Unmasking a culture of corruption

EssayWITH THE PASSING of thirty years since Queensland’s Fitzgerald Inquiry and its seminal report, an opportunity arises to sit back and review the era...

White justice, black suffering

ReportageDad began this job in 1989 in the days of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. He was not the only black prison guard on staff – in fact, at one point, Rockhampton’s jail had the highest percentage of Indigenous employees in the state. And yet, there were even more Murris locked up. The first thing that shocked Dad was just how many were inside, and over the next two decades he would see many of his own relatives coming through the gates.

Cancelled on the overground railroad

GR OnlineTHE ISSUE OF call-out culture (or its monstrous cousin ‘cancel culture’) has been heavily debated in recent times. As punters we find ourselves begging...