Featured in

- Published 20250805

- ISBN: 978-1-923213-10-4

- Extent: 236pp

- Paperback, eBook, PDF

ON A WET Friday in early spring 2024, I’m driving alone through the river flats and undulating pastures of Melbourne’s north-west. I pass cows grazing in green-brown fields, eruptions of prickly pear cacti, one after another. Attached to one property’s fence is a banner: SAY NO TO AUSNET’S TOWERS. A few kilometres on, a steep incline announces itself as being unsuitable for trucks and buses. The tiny hatchback I’m driving trundles onward beyond the last point at which large vehicles can safely turn around and head back towards the comforting bosom of the big city.

My destination is one of those sprawling outer-metropolitan community centres that host youth groups, spiritual retreats and team-building weekends. For the next three days it will be home to the fortieth Australian Wiccan Conference (AWC), a ‘national event for witches of all paths’.

As I pull into the community centre’s car park, a familiar anxiety razors through me: I shouldn’t be here. These aren’t my people. My fingers itch towards my cigarette case and hipflask – habitual crutches – but I resist these impulses and remind myself why I’m here: to meet witches and maybe write about the resurgence of nature-based religion in Australia.

My friend Simon, an Adelaide-based musician, had been the one to invite me. Explaining he was due to play a gig with Spiral Dance, a band with a legendary reputation in Australia’s alternative spirituality scene, he had failed to mention the event was, in fact, a three-day conference with a ticket price to match. Still, he had planted a seed – and here I was, eight months later, sitting in my car wondering where my professional interest ended and where I was, if anywhere, on the path to becoming a witch.

A COMMON JOKE in pagan circles goes something like this: ask ten pagans what a witch is, and you’ll receive ten (or twelve) different answers. Nevertheless, some definitions are in order.

The word ‘pagan’ traces its origins to the Latin term pagus, meaning a district or city ward. A paganus referred to a local inhabitant, often denoting civilians, outsiders or rural dwellers in Roman times. Eventually, European Christians began to use ‘pagan’ to distinguish non-Christians, implying the worship of false gods. Today, the term has been reclaimed by neo-pagans to describe a gallimaufry of spiritual beliefs and practices – including Wicca, druidry, animism and others – that draw inspiration from pre-Christian religions and their shared tenets of nature worship, polytheism and reverence for the Earth.

The anthropologist Lynne Hume, author of Witchcraft and Paganism in Australia (1997), captures the definitional bagginess of the terms ‘witch’ and ‘pagan’ well:

All witches are pagans, but not all pagans are witches. Individuals who refer to themselves as simply ‘witch’, and do not belong to any particular branch of Wicca, say that they are witches because they live the life of a witch, follow the seasons and the moon’s phases, feel close to nature, know something about herbs, and are psychic. Wiccans are witches, but not all witches are Wiccans. Some say that they follow the Craft or the Old Religion but there are differences of opinion on just what this means… Others say that they are Wiccan, but even the term ‘Wicca’, a more specific set of beliefs under the rubric of paganism, has many forms.

If that gloss strikes you as abstruse, it may be helpful to think of paganism as one might of Christianity or Islam: not as a homogenous set of beliefs and practices, but rather as an umbrella term under which commingle a range of religious traditions. A common thread among all pagan traditions is a deep reverence for the natural world, particularly the cycles of the seasons and the moon. They also share a belief in magic – often spelled magick following occultist Aleister Crowley’s coinage to distinguish it from the practices of stage magicians – a concept involving perceiving beyond the physical senses and influencing the world through ritual, mental focus and tapping into various extramundane forces.

Unlike the patriarchal and monotheistic Abrahamic religions, paganism is structurally non-hierarchical – although covens (groups or meetings of witches) tend to be nominally led by a high priestess and high priest – and, in the words of influential English Wiccan Vivianne Crowley, pagans ‘worship the personification of the female and male principles, the Goddess and the God, recognising that all forms of the Goddess are aspects of the one Goddess and all Gods are aspects of the one God’. There is no holy book, messiah or central administration, and its ethos is fundamentally exultant – celebratory of the body, nature and the divine.

To clarify a common misconception: most pagans neither believe in nor worship Satan, a figure rooted in Judeo-Christian traditions rather than nature-based spiritual paths. The conflation of pagans with ‘devil-worshippers’ dates to the twelfth century and is a product of the Catholic Church’s campaign to quite literally demonise the horned, cloven-hoofed gods – Pan, Herne, Cernunnos and others – central to the pre-Christian spiritualities the Church was intent on suppressing.

The witch trials of the early modern period, where accusations of devil worship were frequently levelled against those, usually women, who practised folk magic, herbalism or traditional healing (or, in many cases, had simply drawn the ire of a relative or neighbour), reinforced the association between nature-based religion and Satanism. As the historian Ronald Hutton observes in The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present (2017),the standard scholarly definition of ‘witch’ has come to denote, in the words of anthropologist Rodney Needham, ‘someone who causes harm to others by mystical means’.

It is unsurprising, then, that the witch has historically been linked to sinister deeds and the evoking of fear. I have, in fact, started to wonder whether this idea of the witch is a kind of proto-conspiracy theory, a channelling of anxieties around our benightedness and lack of agency towards a small but powerful group of conspirators.

Yet, as Hutton notes, this definition now exists alongside several others: a person who practises magic, whether harmful or benevolent (such as the ‘good’ or ‘white’ witch); a follower of a pagan or nature-based faith; and a symbol of women’s autonomy and defiance against male oppression. If anything, these multiple interpretations, veined as they are with ideas of female empowerment, pantheism and the natural world as sacred, do little to allay the witch’s ambiguous and marginal status in a time of resurgent patriarchy and conservative ideology.

IT IS OFTEN said that what early Christians could not eradicate of paganism, they instead assimilated, adopting its beliefs, festivals and rituals. That may be so – though, for the most part, paganism, far from being an ‘ancient’ tradition, is no older than the mid twentieth century. At the same time, while fear of witchcraft persists – most distressingly in sub-Saharan Africa, where witch hunts and ritual child abuse continue – nature-based religions in the modern era are just as likely to be met with scepticism or mockery as with outright suppression or co-option. Us knowing, ironising moderns tend to ridicule rather than seek to understand, a habit amplified by social media’s perverse incentivisation of our most censorious instincts.

A few days before the conference, Josephine, a witch, author and member of the AWC committee, told me they had turned down an approach from a major daily newspaper to send a journalist to the event. The newspaper, apparently, had attempted to reassure the committee by saying they had experience writing about ‘carnival types’.

When I first approached Josephine by email, she told me there had been something of a schism in response to my interest. The younger members, no doubt savvier marketeers who had come of age in a less captious time, were unfazed by the idea of my attendance. The older members, on the other hand, were generally wary; they had been (figuratively) burned too many times before. I was told stories of newspapers that had ‘outed’ pagans – with photographs – having failed to seek consent; of endless Halloween-timed articles written with the intent to place witches alongside furries, Lolitas and LARPers as unserious fantasists.

The Pagan Awareness Network lists the ten most common media misrepresentations of pagans and witches on its website. Number five protests mention of ‘bed-knobs, broomsticks, cauldrons, warts, the words “ding” and “dong”, “bubble” and “trouble”, capes, pointy hats, or spells’. Another reads: ‘By associating pagans with modern commercial Halloween celebrations, you are implying that we, and our beliefs and traditions, belong in the realm of costumes, monsters and make-believe, rather than being a “real” religion. Come visit at winter solstice instead.’

On my way to the conference registration desk, I see an old Mitsubishi adorned with a Ukrainian flag and a placard reading P.A.N.: PAGANS AGAINST NUKES. Attendees I pass wear pentacle necklaces and hoodies inscribed with ‘Emo’s Not Dead’ and ‘In Odin We Trust’. (‘Young people,’ one of the committee members will tell me over dinner that night, ‘are attracted to Norse mythology.’) There is less velvet than I’d expected, and only one pointy hat as far as I can see. Quite a few people have brought their own elaborately decorated chalices. (In an email sent before the conference, attendees had been warned not to pack their athames – ritual blades that, while intended only for use on the ethereal plane, are regarded as prohibited edged weapons under Victorian law.)

At the desk I’m handed a welcome pack containing, among other knick-knacks, two wands made from applewood (‘magically associated with love, fertility, protection and prosperity’ and ‘especially suited for emotional magic, or love rites’, according to an attached explanatory note) and a Rider-Waite tarot card. It’s the Empress – indicative, I learn later, of ‘fruitfulness, action, initiative, length of days; the unknown, clandestine; also, difficulty, doubt, ignorance.’

THE AWC WAS established in 1984. Traditionally, the conference takes place every year on the weekend nearest to the spring equinox (on or close to September 21 in the Southern Hemisphere), a festival redolent of new life and balance for pagans as the hours of daylight return to equilibrium with those of night. Each year, a different state hosts the conference, with organising duties assumed by various covens or community groups. The event format, much like the craft itself, focuses more on praxis than theory: workshops, lectures, a spring ritual, a market, evening entertainment and, finally, what pagans refer to as a ‘moot’ – an Old English word for a meeting or assembly.

There are perhaps 120 people at this year’s conference, 60 to 70 per cent of whom I estimate to be women. Many are middle-aged, and almost everyone is white. The program features presentations and lectures on alchemy, the Wheel of the Year, pop culture fandom as religion (‘Geekomancy’), and hardcore literary and theological discourses on Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899), American folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland’s foundational Wiccan text, and on whether ‘Christian Theoria’ can make you a better witch. Workshops detail the making of scrying mirrors and witches’ bells, and this year’s market – although many people I speak to are at pains to de-emphasise witchcraft’s consumerist turn – brims with herbal besoms, tarot decks, candles, jewellery and alchemical tinctures. (I try, at alchemist Benjamin Turales’ session on medicinal alchemy, gold oil, which tastes exactly like the high-proof liquor that it is.) ‘Then, now, next’ is this year’s theme, a suitably middle-aged tagline betokening reflection, appraisal and envisioning. In what I take to be a delicious piece of witchy providence, the conference and I are the same age.

As the organisers bustle about in the kind of good-humoured chaos typical of ambitious community events like this – unexpectedly, the main hall’s stage has been dismantled, potentially forcing Spiral Dance to perform on the floor – I strike up a conversation with a member of the AWC committee I’ll call Terri, whom I guess to be in her late forties or early fifties. She was, she says, up until recently ensconced in Sydney’s corporate sector; I sense the desire for a tree- or sea-change behind the shift. Like many here I speak to, she describes herself as a ‘nineties witch’, someone whose formative years coincided with that decade’s boom of witchy pop culture – epitomised by films such as The Craft and Practical Magic, and TV shows such as Charmed, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Sabrina the Teenage Witch. (My touchstone, by contrast, was The Witches, Nicolas Roeg’s 1990 film of Roald Dahl’s arguably misogynistic book, which hewed to a much more old-fashioned and infinitely less empowering view of witches as malignant, shapeshifting crones.)

Her husband, she tells me, is also a pagan, and her two teenaged children are on the same path. (Children can undergo a ‘Wiccaning’, a ritual comparable to baptism whereby they are placed under the protection of the gods, but pagans generally believe that people must be able to freely and consciously choose a spiritual practice for themselves.)

When I ask Terri about her perception of paganism’s demographics, she suggests that young people are ‘coming through’ but says there is a reluctance among them, especially post-pandemic, to gather in person. ‘WitchTok’ – the catch-all term for witch-themed TikTok videos often focused on spellcasting, which have collectively amassed billions of views – is where it’s at. The prevalence of witchcraft on social media might seem antithetical to paganism’s spirit of earthy connection and gives rise to more than a few withering remarks at the conference. But for all the accusations of WitchTok as ersatz – to whit, the case of the TikTok ‘baby’ witches who reportedly put a hex on the moon – I begin to wonder if it doesn’t, in fact, harken back to the long-established tradition of the ‘solitary’, a witch who practises solo rather than with a coven.

Pagans believe that, just as individuals have the freedom to choose their own spiritual path, they also have the autonomy to practise their spirituality in a way that is personal and self-directed. Rather than requiring conformance to a specific group or community – where beliefs and practices might be subject to external scrutiny or judgement – many pagans embrace a more independent approach to the making and unmaking of spiritual frameworks. Thus, intuition and direct experience in matters of faith are elevated, encouraging distinct and personal connections with the divine and nature, free from deference to institutional authority – which has, in any case, been eroded by systemic scandal and corruption in many churches, and an attendant disillusionment with their hypocrisy and failure to reform. Just as contemporary paganism’s embrace of diverse sexual and gender orientations marks it out as distinctively modern, so too does its organisational looseness and lack of hierarchy, its adherents nodes in a decentralised network of empowered practitioners, informal communities and fluid beliefs and practices.

Terri tells me that increasing numbers of queer and gender-diverse pagans are emerging from the ‘broom closet’, an observation Josephine readily agrees with when I later put to her my intuition – reflected, as it turns out, in countless #queerwitch posts – that LGBTQI+ folk are inherently more magic(k)al. At the same time, it isn’t hard to see why spiritually inquisitive people with non-normative and fluid gender and sexual identities would turn to paganism over mainstream religion, with its obsessive twinning of (especially queer) sexuality and sin, and its tendency towards tribalism and other forms of inflexible thinking. As Amanda Kohr, an LGBTQI+ writer and former born-again Christian cult member, writes:

Regardless of the specificities of their practices, all queer witches seem to have one major thing in common: a desire to feel empowered and the freedom to explore their identities. Perhaps this is what makes the intersection of the queer community and witchcraft so natural – they are both expressions of otherness.

PAGANISM’S POPULARITY IN Australia, along with that of other nature-based religions, is steadily growing. According to the 2021 Census, 33,148 individuals identified with animism, druidism or some variety of Wicca – up from 27,207 in the 2016 Census (affiliation with Christianity declined during the same period). The Census also tells us that 66 per cent of pagans are women, and that Tasmania is home to the most pagans of any Australian state or territory. These numbers, while a useful snapshot of the increasing rate at which Australians are adopting nature-based faiths, are likely to be unreflective of the true figures. Declaring a religious affiliation on the Census is optional and, as Ronald Hutton has noted, ‘most of the pagans with whom I’ve kept in touch do not enter themselves on the Census’ – a fact no doubt at least partly attributable to stigma.

While laws prohibiting witchcraft in Australia, derived from Britain’s Witchcraft Act of 1735, have all been repealed – the last, remarkably, as recently as 2013 – many pagans remain wary about the open acknowledgement or practising of their beliefs. Every pagan seems to have a story of someone they know being refused or dismissed from a job, or cast out from one or another familial or social circle, on account of a belief in witchcraft.

Still, the rise of nature-based religious beliefs and practices has been sufficient for journalists such as The Guardian’s Emma Beddington to ask: ‘Is paganism, a loosely defined constellation of faiths based on beliefs predating the main world religions, going mainstream?’ (Beddington cites a 2014 Pew Research Center survey suggesting there are about one million pagans in the US, a number that may triple by 2050.)

That seems a stretch, but the appeal of nature-based faiths in the early twenty-first century isn’t hard to fathom. In a time of ecological crisis, the veneration of nature and acknowledgement of non-human subjectivities look less like the Victorian era’s romanticisation of the natural world – a reaction to rapid industrialisation and urbanisation – than a survival instinct. It’s no mystery, either, why those seeking connectedness and spiritual fulfilment but repelled by mainstream religion’s dogmatism and intolerance should be turning to paganism in increasing numbers.

In an era defined by precipitous techno-capitalist advancement and the lingering influence of ontological dualism, where materialism and extraction remain dominant paradigms, I can’t help but wonder if paganism also answers our yearning for re-enchantment. As modern life becomes ever more digitised and secularised, paganism’s worldview – encompassing a deeper, more spiritual connection to the world around us, and recognising the sacred within the everyday – seems to speak to the innate human desire to see the world as suffused with meaning and animate intelligence and, above all, wonder.

WE’RE NOT SUPPOSED to drink before the ritual, but I sneak a few quaffs of Fireball from my hipflask with one of the organisers I’ve become friendly with. It’s drizzling again, and cold, so we shelter under a wattle tree as most of the conference attendees retire to their dorms to ready themselves. As my friend excuses herself to prepare, I suddenly feel self-conscious about participating in the ritual – ‘a religious service’, we are reminded in the conference program, ‘in which considerable power may be raised’ – in my everyday clothes. I yank off a sprig of wattle to wear as a boutonnière on my lapel. Perhaps, I reason, this is my modest tribute to the Green Man, the vegetal, pagan-adjacent figure from European folklore symbolic of spring and rebirth.

Somewhat disappointingly, the ritual has been relocated from the site’s oval to the main hall due to the inclement weather (I think I had been imagining, and perhaps hoping for, if not an actual wicker man, then at least something involving fire). By the time I trudge up the hill as the sky is beginning to blacken, a large group of witches has gathered outside the entrance to the hall. Their robes and cloaks, many clearly handmade and adorned with pentacles and other symbols, create the illusion I have somehow slipped backwards through time. It’s hard, too, not to see all this distinctly European garb as a kind of imposition on the landscape, a spatial as well as temporal anomaly in this arid, sun-scorched place.

Eventually we are ushered inside, and the ritual unfolds beneath the hall’s harsh fluorescentlights like a cross between a civic function, an amateur play and a harvest festival in miniature. There are roles – for both the organisers, who are clearly well-rehearsed, and the rest of us, who have been duly informed ritual is not a spectator sport – lines and formalities. True to Emma Beddington’s claim that ‘no one sacrifices anything except food and drink these days’, no animals come to any harm, and there is no nudity nor any sex magick in evidence (going nude or ‘skyclad’ is a feature of pagan ceremony, as are rituals, including one known as ‘the Great Rite’, which involve sexual intercourse, but few people at the conference seem eager to broach the subject, at least with me).

The gist is the banishment of winter – ‘dark calls to light, winter to the spring,’ we chant, ‘the greening of the earth, calling summer in’ – and the welcoming of the new season in the form of a spring queen and consort, chosen at random from nominated conference attendees. Pagan etiquette dictates that it’s considered gauche to describe the ritual in detail. But what strikes me is its ordinariness: for all the mainstream’s condemnation of paganism as profane and even dangerous, this is a small group of friendly, well-meaning people marking the transition of the seasons by way of some amateur dramatics and the breaking of bread together. I’d be lying if I said the propaganda hadn’t got to me in a way as well – to be honest, I’d been hoping for something a little edgier.

That evening, as is customary following a ritual, we feast. As I tuck into a plate of vegan sausages and roast vegetables, someone jokes that at pagan gatherings ‘there are more neurodivergences and food intolerances than there are people’. Then we dance. Nobody seems to mind that Spiral Dance has ended up on the same level as the audience. I can’t bring myself to dance at first – I’m not drunk or high enough and the band, though superb, are not exactly my chalice of tea – but I’m talked into it by Jane, a Blue Mountains witch and writer who shares her intuition that I have trouble getting out of my own way. I’m taken aback by the witchy prescience of this. My lifetime’s habit has been to hover on the periphery, maintaining a journalist’s objectivity in the face of forces that might otherwise pull me in deep,

subsume me.

I get to my feet just as the dance the band is named for – communal and circular, symbolic of life and rebirth, and representative of the goddess in its counter-clockwise motion – is beginning. Just before I’m swept up in the dance, and the band’s joyous music happily drowns out my own thoughts, I remember something I heard earlier that day: that Wiccans’ answer to the problem of being a witch is to give you a community.

A FEW MONTHS later, I speak with Josephine again. She tells me that, as in 2020, 2021 and 2023, this year’s forty-first AWC will be virtual. It’s not the pandemic this time – their public liability insurance has been ‘delayed’ and their usual ticketing agent is, apparently, not playing ball either. I wonder aloud if these are signs of a backlash, a reflection of the world’s seeming turn towards illiberalism, and Josephine doesn’t disagree.

There is an idea in the pagan community, first put about by the Appalachian witch Byron Ballard a decade or so ago, that we are living through something called ‘Tower Time’. Named for the Tower tarot card, which in the Rider-Waite deck depicts a tower topped with a crown being struck by lightning and symbolic of misery, deception and calamity, Ballard defines this era as one in which old and toxic systems, both constitutive and ultimately destructive of civilisation as we know it, are collapsing under the weight of their own history. ‘It is,’ Ballard writes, ‘the death throes of patriarchy that we are experiencing, and it will die as it has lived – in violence and oppression and injustice and death.’ (The Tower is, interestingly enough, a ‘trump’ card in most tarot decks.)

If the AWC’s fortunes are anything to go by, and a counter-reaction to the resurgence of nature-based faiths is underway, then it is tempting to think Ballard’s idea captures something important about why this might be so. ‘Our work during the collapse,’ she writes, ‘is to not stop there, gawking at the impending calamity. We are charged – and many people are deep into this work – with creating new systems, systems that are genuinely co-operative, nurturing, sustainable and, of greatest importance, resilient.’

Or, in the words of Perth-based Wiccan Peregrin Wildoak, perhaps all it is incumbent on us to do in the face of catastrophe is ‘just let go and love the goddess’.

References

Ballard, B 2016, ‘The Tower Time Documents, Uncut’, My Village Witch, https://www.myvillagewitch.com/the-tower-time-documents-uncut/

Rakusen, I 2023, Witch, BBC Radio 4, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001mc4p/episodes/downloads

Beddington, E 2023, ‘Dawn of the New Pagans: “Everybody’s Welcome – as Long as You Keep Your Clothes On!”’, The Guardian, 27 April, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/27/dawn-of-the-new-pagans-everybodys-welcome-as-long-as-you-keep-your-clothes-on

Browning, H 2021, Vimeo, Under a Pagan Sky, Tidal Films, https://underapagansky.vhx.tv/products/under-a-pagan-sky-documentary

Guiley, RE 1989 The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft, Facts On File Inc, New York.

Hume, L 1997, Witchcraft and Paganism in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South.

Hutton, R 2022, Pagan Britain, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Hutton, R 2017, The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present, Yale University Press, New Haven.

Kohr, A 2021, Why Queer People Love Witchcraft, Refinery29, https://www.refinery29.com/en-au/2021/07/10533154/queer-lgbt-witch-trend

Matthews, C (Ed.) 1990, Voices of the Goddess: A Chorus of Sibyls, Aquarian Press, London.

Meredith, J 2013, Rituals of Celebration: Honouring the Seasons of Life through the Wheel of the Year, Llewellyn, Woodbury.

Pagan Awareness Network n.d., ‘Home’, https://www.paganawareness.net.au/

Image courtesy of Eda Norton from Unsplash

Share article

More from author

Fire and finitude

Nobody any more seriously doubts that cigarettes are injurious… What is not well understood by those opposed to smoking is that the danger of cigarettes is not antithetical or even peripheral to their appeal – it is central to it.

More from this edition

Gallows humor

Fiction THE TOWN’S FLOWERS have set seed in the late-spring wet hot air, as the land prepares for the rains. It is nearly hatching time...

Man’s Labyrinth

Non-fiction GOD MAY WORK in mysterious ways, but senior bureaucrats are damned near inscrutable. Towards the end of 2024, as the managers in charge of the...

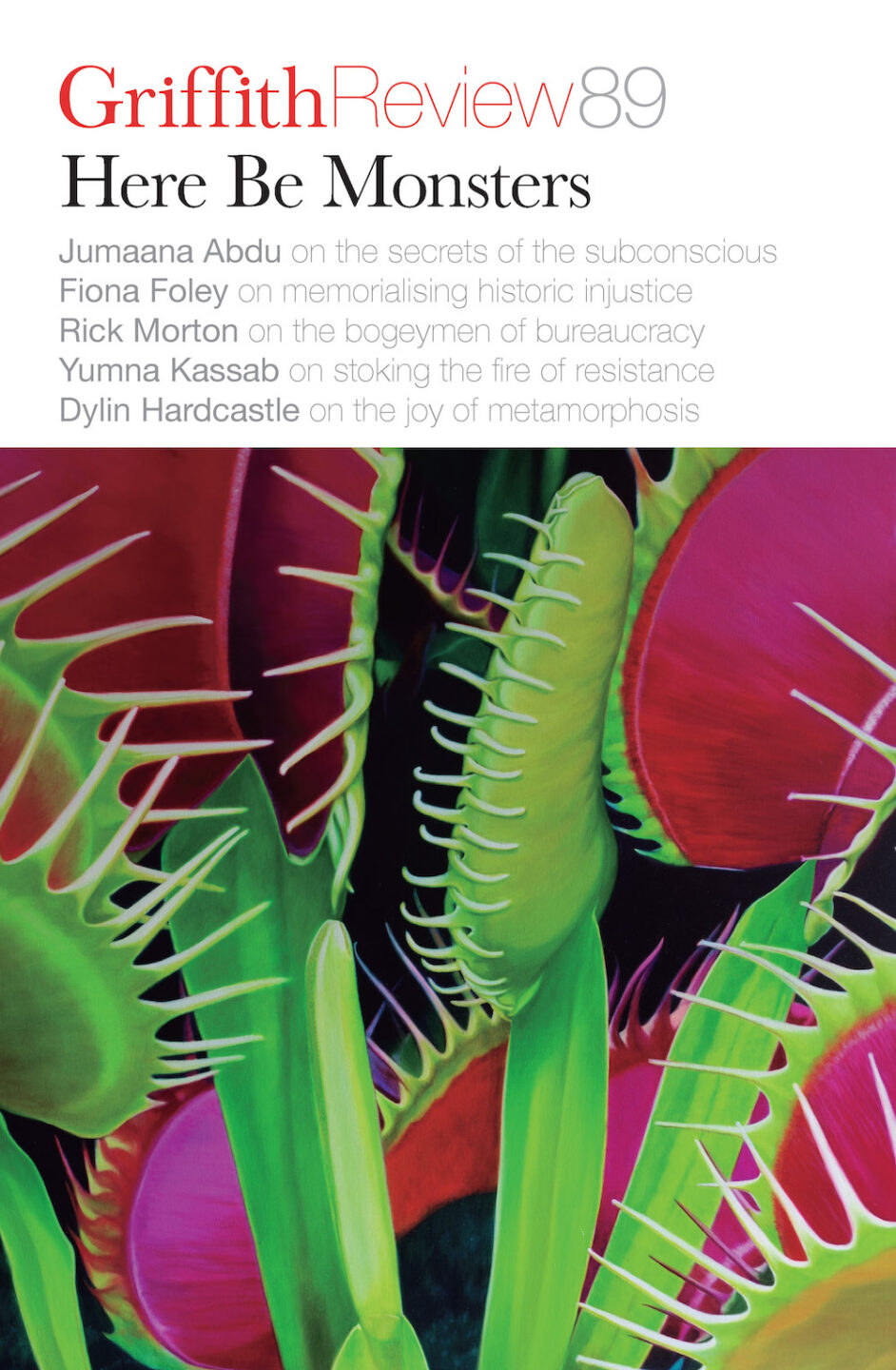

Subject, object

GR Online The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89:...