Journal

Articles

All creatures great and small

There are strong links between public opinion and the direction of scientific research, conservation funding and legislated policies, meaning that biases in the way we communicate about species within popular culture have tangible effects: the most favoured species receive the bulk of our research efforts, conservation initiatives, academic publications, ecotourism visitors and threatened-species listings. At a time when global biodiversity is rapidly declining, then, these trends raise concerns for at-risk species that don’t enjoy a prominent or positive public profile.

A storyteller’s journey

You produce content and people say, ‘Oh, you need to tell people about this, or the Stolen Generations, or the stolen wages.’ We’ve still got to repeat that story, which should have been told and embraced by Australia, as ugly as it is, so we can move on. So, I started telling my own stories for me and my people to remind us what a great culture we have. As human beings, we’re pretty deadly.

Unhappy pairings

Arts, creative arts and humanities courses teach critical thinking, civic discourse, emotional literacy and storytelling. Most students are grappling with rent, menial work and advanced study. In a world that seeks to destroy their attention span, arts courses teach young people to read, think critically and provide historical context and sensitivity to complex issues.

The many tragedies of Animorphs

Animorphs has been out of print for twenty years, yet its cult following remains fierce. If your knowledge of Animorphs is limited to the cover art, I’m sure that’s a bemusing claim to read. However, if you did read the books, then the unlikely endurance of Animorphs is really anything but.

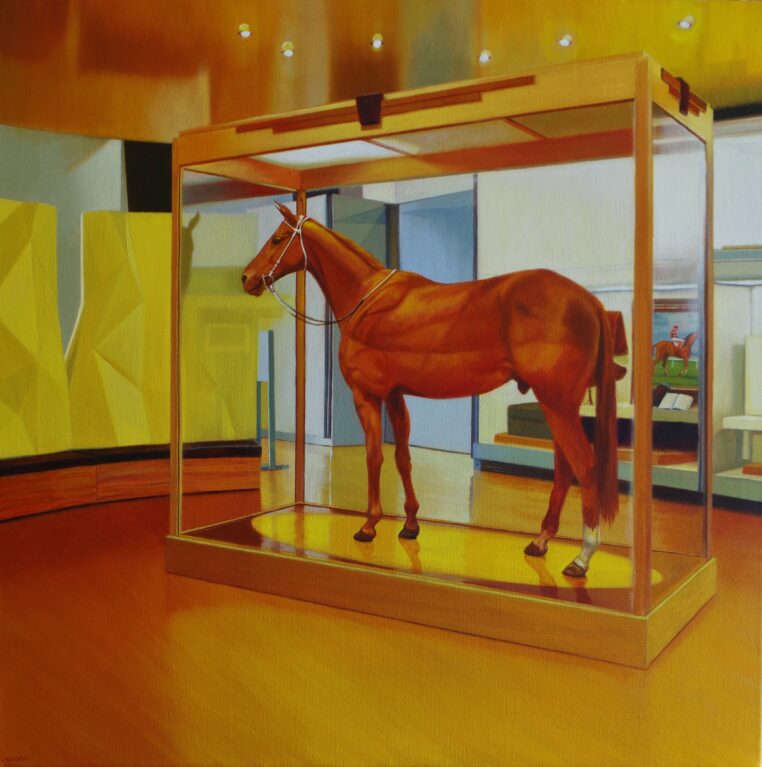

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

Real monsters

The language of horror, with its ability to conjure the unthinkable, to trace the contours of our deepest fears and darkest imaginings, can lead us into those shadowy corners of the human psyche, giving us permission to peer into the gloomy space under the bed or creak open the door to the basement. It allows us to sit with the uncertainties of life.

Operation Totem

In the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of atmospheric and underground tests were conducted in Australia, with devastating consequences for First Nations peoples and for the military personnel involved in the tests. And yet the debate about Peter Dutton’s plan to put Australia on a nuclear track barely mentioned this calamity, or indeed the deep antipathy towards all things nuclear to which it gave rise. Struggling to put Dutton’s policy in context, one looked in vain for even a passing reference to Dr Helen Caldicott, Moss Cass or Uncle Kevin Buzzacott; to the Campaign Against Nuclear Energy or the Uranium Moratorium group; to the seamen’s boycott of foreign nuclear warships in Melbourne in 1986; to the massive antinuclear marches of the 1970s and 1980s; to Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta and its resistance to the dumping of radioactive waste. Indeed, one looked in vain for any sense of nuclear as a uniquely dangerous technology, or of the ‘deadly connection’ (as Jim Falk called it) between uranium mining, nuclear reactors and the development of thermonuclear weapons.

A nation’s right to remember

In a 2023 article published in The Guardian, the Australian War Memorial’s newly appointed chair, Kim Beazley, acknowledged, ‘We do have to have a proper recognition of the frontier conflict.’ In an interview with Beazley on the ABC’s 7.30, journalist Laura Tingle reported that of the 27,000 metres of new space in the expansion, the pre-colonial gallery, which includes the Frontier Wars, would make up less than 2 per cent, and asked, ‘Will that be sufficient?’ Beazley’s reply was, again, ‘we need to have that recognition around the country’, while he emphasised that other institutions should play a role in the telling of Australia’s Frontier Wars. A charismatic sidestep.

The coward

At the beginning of my research, I knew little about Anne. I knew that my aunt had been married to an Anglican reverend. I knew she was Dad’s half-sibling, from my grandfather Staniforth Ricketson’s first marriage. I knew that she lived in the country at Mount Macedon. The final thing I knew for certain: my aunt died a sad and violent death. She perished on 16 February 1983, the night of the Ash Wednesday bushfires. Her husband, the Reverend Bill Carter, drove away from their cottage without her. In his panic, he left his wife behind and saved himself as the flames closed in.

Stories of cowardice, unlike those of courage, make us deeply uncomfortable. Coward is a label we generally affix to those we call monsters: terrorists, paedophiles, predators. But cowardice does not just exist at the extremities of behaviour – it is both more quotidian and more human than that.

Man’s Labyrinth

Max Weber foresaw the iron cage of rationalisation coming for us all: that industry and its social institutions would become so technically efficient that a worker would become a ‘specialist without spirit’ and a consumer a ‘sensualist without heart’. People could have everything they’d ever wanted, in theory, but the cost would be their humanity.

Weber conceived of this as a prison of capital when workers were in factories and those factories increasingly required employees to take on smaller and more specialised roles. This stretched into the bureaucratic sinew of large businesses and corporations, naturally, and into the administration of states, municipalities and even sufficiently large Zonta clubs.

The fire this time

When I think about this period now I see that my life has been one long exercise in walking back from a bridge and talking down a fire. The bridge has always been what is the point of this and the fire has always been an overwhelmingly destructive energy that threatens to consume everything. One is an anger turned inwards while the other is directed outwards, the building is burning and there is nothing to save in all of humanity.

One continuous showdown

The driver picks me up from Mumbai airport and drops me off in front of the hermitage entrance, at the foothills of an ancient fortress. Decades earlier, when the guru and his wife purchased the land, they kept panther-watch at night. I’m in the right place, aware of my own monster still prowling about