For the love of our children

A special series in celebration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages

Featured in

- Published 20191105

- ISBN: 9781925773804

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this essay contains the names of people who are deceased.

IN 2012, THE United Nations held a forum for its Study on the role of languages and culture in the promotion and protection of the rights and identity of indigenous peoples. The following quote from that forum captures the global importance of language:

Language is an essential part of, and intrinsically linked to, indigenous peoples’ ways of life, culture and identities. Languages embody many indigenous values and concepts and contain indigenous peoples’ histories and development. They are fundamental markers of indigenous peoples’ distinctiveness and cohesiveness as peoples.

That same year, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs held the Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities. The Warlpiri education organisation Warlpiri-patu-kurlangu Jaru Inc. made a submission to the Inquiry that included this statement about how essential language is to their community in Australia:

Knowing that our own language and culture play the biggest role in growing our spirit, our connection to our land and the stories of our grandmother and grandfathers. With our language we know where we belong, we know the names from our country and Jukurrpa (Dreaming stories and designs). Young people can’t lead a good, healthy and happy life without this. Language and culture come first. When kids feel lost and their spirit is weak then they can’t learn well or be healthy. They need to feel pride in their language and culture and know that they are respected. That’s the only way to start closing the gap.

In 2014, Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey was published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. In the survey, 102 speakers and representatives of 79 languages and four language groups participated in identifying the state of their own language’s importance, maintenance and future. All language groups responded in strong favour of community language classes, workshops and resources for children, enabling kids to strengthen their literacy and maintain their languages as an integral part of daily life in communities.

In 2019, in response to accumulating concern regarding the survival of the world’s oldest languages, UNESCO has held the International Year of Indigenous Languages.Many linguists, community language centres, educators and elders have played enormous roles in Australia’s participation in this venture. The organisation First Languages Australia has tirelessly worked to ensure that the cultural, spiritual and historical weight locked in living languages stays alive.

When examining the role of language and publications in relation to our children, it’s important to remember that English is the second, third, fourth or least used language to many Indigenous people still alive and thriving today. The challenge in educating our children holistically is threefold: our education system should balance and honour our intact Indigenous languages across Australia; it should celebrate those languages, cultures and people by allowing linguistic fluidity in the classroom; and it should allow our people to engage in connection and healing through language via supportive community projects or rehabilitation programs. That is the work of decolonising the mind and tongue. Finally, I think that as a nation, Australia has an opportunity to embrace the mother tongues of where we live, whether by supporting local language centres or lobbying for First Nations language programs to be taught in local schools and as part of early-childhood curriculums. This will allow us all to feel a sense of belonging in relation to our cultural history as a nation, openly acknowledging the horrors that have been committed and giving ourselves a real chance to be proud of our country’s future and the resilience of our First Peoples.

This is my last word in this essay series, and I had hoped to list all the wonderful children’s and young adult books published by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors. That task has proved impossible – I would’ve needed another eight essays to cover the wealth of books available and to do these genres justice. I could have just listed those titles known to me, but inevitably I would have missed something community-published, something sacred to a particular language group.

Looking though the many titles on my shelf, I spotted my daughter’s favourites, the ones she insisted I read over and over every night. They include Big Rain Coming by Katrina Germein and Bronwyn Bancroft (Penguin, 2002), A is for Aunty by Elaine Russell (ABC Books, 2001), Aboriginal Story: How the birds got their colours by Pamela Lofts and Mary Albert (Scholastic Press, 2004) and Kakadu Calling by Jane Christopherson (Magabala, 2007).

My daughter and I are bound together in these stories; her childhood is attached to the times I’ve read them to her, and the times after, when she learnt to read them to herself. I heard my old reading voice again, the one I used as I sat beside my daughter’s bed or propped myself in a chair with her back resting against the heartbeat in my chest, the book in front of us and my finger dragging gently below each word as I said it aloud.

There is something so special that remains in the books we read our children. We, the parents, learn these stories by heart, and our kids do too. We teach them the rhythm of the words, we teach them when the story changes pace and we have to speed up, get excited – something is about to happen! Ultimately, we teach them to read. They learn by following the words, and by imitating the tones and sounds and jumble of breaths in and out, making pictures appear from letters.

The act of reading to my daughter is one of my greatest and most precious memories of her childhood. I will remember and cherish that time forever. I’m so thankful I took that time to read to her, every night, on the road or at home. It shaped her into an avid, passionate reader and helped her become bilingual and learn multiple languages. Her literate brain helps her grapple with the complexities of learning that arise to this day.

My daughter, though, is privileged – since she was a baby she’s been surrounded by books, not only as the child of a writer, but because she was always on book tours, at festivals, being gifted books, being held in the arms of writers in a green room or beneath a literature festival marquee. At two, she accompanied me through remote Northern Territory Aboriginal communities to deliver books to kids and visit newly stocked libraries that had been assisted by the Indigenous Literacy Foundation (then the Indigenous Literacy Project), which provides hundreds of thousands of books to such communities and produces books in language each year. It is one of the many organisations that contributes to language-reclamation projects and publishing the early-learning board books and community-initiated storybooks that are so vital.

Not only this UNESCO year, but every year.

The importance of books for children now, the ever-evolving need to tell our own stories and to hear them read back to us, is paramount to fostering healthy and happy minds.

I spoke to a friend recently who told me about the seven-minute Acknowledgement of Country her daughter does at preschool each morning. An Elder visits the school to teach language, songs and dance, and art-making. The hours when the local Elder visits are my friend’s daughter’s favourite. Next year, she’ll start primary school.

I asked my friend, What happens when she goes to primary school?

My friend didn’t know if the primary school would perform the Acknowledgement of Country or conduct the language classes.

What we need is for parents to ask for these things. To probe our school principals on their principles. We need to ask publishers: What own stories are you bringing out next year? How will you include and not exclude linguistically diverse kids?

Our next generation of readers represents the first step towards finding our next generation of writers. The bilingual titles we need published are essential to our mob – we need stories to raise us, to comfort us, to make us feel that we belong. We need characters like us to champion.

The absolute outpouring of quality titles from Magabala Books cannot be overlooked. Every bookstore in Australia should have a stockpile of these titles – Magabala is a publishing house whose books are truly changing the landscape of Australian readers. Other publishers should be looking to Magabala’s innovation. Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kids need these stories in their most important languages to support their journey in preserving and promoting a mother tongue. More and more children’s books are being produced by Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages, Batchelor Press, Binabar Books, IAD Press, Kaurna Warra Pintyandi, the Maningrida NT Language Support Program, the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre and so many others around the country.

What is imperative, and what I really have wanted to say in this essay series, is that we are truly at a crossroads. We have this infinite wealth of stories available, stories that are continuing to be published, stories that will be the cornerstone for change in the narrative we tell ourselves as Australians.

This is our call to action: to read these books, to support the industry, to talk about language with our leaders and teachers and the caretakers of our children. To decolonise our shelf is not to rewrite history, but to learn it, finally. Letting all our kids have a truthful chance at understanding the past and creating a brighter future.

Here are just a few titles – I hope you discover others, too.

Thank you for reading. In the Wiradjuri language, mandaang guwu.

Board books

The Butterfly Garden by Michael Torres, illustrated by Fern Martins (Magabala, 2019)

A bright and happy story for babies.

In the Bush I See by Kiara Honeychurch (Magabala, 2019)

This beautiful search for animals in the bush is part of a brilliant board book series.

Can You Dance? by Sally Morgan, illustrated by Kathy Arbon (Indigenous Literacy Foundation, 2018)

A rollicking little dancing tale.

Toddlers and young readers

Nintirringanyi Ngurra Ku: Learning on Country by Annette Robinson and Roxanne Sharpe, illustrated by Dianne Williams (Children’s Ground, 2019)

The story follows the learning kids undertake out bush, and is written in Luritja, Warlpiri and Eastern Arrernte languages and in English.

Little Bird’s Day by Sally Morgan, illustrated by Johnny Warrkatja Malibirr (Magabala, 2019)

A simple and universal story of a day in the life of a little bird.

Welcome to Country by Aunty Joy Murphy, illustrated by Lisa Kennedy (Black Dog Books, 2016)

This book welcomes kids to the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri people with introductions to the customs and symbols of Indigenous Australia.

From Little Things Big Things Grow by Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody, illustrated by Peter Hudson and kids from Gurindji country (One Day Hill/Affirm Press, 2008)

The lyrics of the iconic song are presented here in a stunning picture book.

Going to the Footy by Debbie Coombes (Magabala, 2019)

All the different ways of to getting to the footy are covered in this beautifully illustrated book.

Baby Business by Jasmine Seymour (Magabala, 2019)

A lovely traditional way of bringing up baby, featuring Darug language throughout.

Yakanarra Song Book by Jessie Wamarla Moora, Mary Purnjurr Vanbee, Alison Lester and Chris Aitken, illustrated by the children of Yakanarra Community School (Indigenous Literacy Foundation)

A Walmajarri and English collection of 14 beautifully illustrated songs about birds, hunting, fishing and more.

How Frogmouth Found Her Home by Ambelin Kwaymullina (Fremantle Press, 2010)

Frogmouth helps the other animals find their true homes.

Silly Birds (Magabala, 2014), Kookoo Kookaburra (Magabala, 2015), Mad Magpie (Magabala, 2016), Cunning Crow(Magabala, 2019) and My Culture and Me (Puffin, 2019), all by Gregg Dreise

A range of brightly coloured and engaging stories from on Country.

Clever Crow by Nina Lawrence, illustrated by Bronwyn Bancroft (Magabala, 2018)

Follow the very hungry and very clever crow searching for bush food.

Cooee Mittigar: A story of Darug songlines by Jasmine Seymour, illustrated by Leanne Mulgo Watson (Magabala, 2019)

The message of joy is for all ages. A great bilingual text.

Our Island by the children of Gununa, with Alison Lester and Elizabeth Honey (Picture Puffin, 2016)

A lyrical celebration of place filled with turtles, dugongs and salt water.

Middle and upper primary

Shake a Leg by Boori Monty Pryor, illustrated by Jan Ormerod (A & U Children, 2010)

A story about the power of song and dance from Australia’s Children’s Laureate (2012–13).

Papunya School Book of Country and History by Papunya School and Nadia Wheatley, illustrated by Ken Searle (A & U Children, 2003)

This book tells the story of how Anangu people from five different language groups came to live together at Papunya.

The Patty Mills series by Patty (Patrick) Mills and Jared Thomas (A & U Children, 2017)

Footy, rugby athletics and a lot of basketball is covered in this inspiring sports series.

Who Am I? The diary of Mary Talence, Sydney, 1937 by Anita Heiss (Scholastic Press, 2001)

An introduction to the Stolen Generations through a young girl’s story.

Young Dark Emu: A truer history by Bruce Pascoe (Magabala, 2019)

A children’s version of Bruce Pascoe’s multi-award-winning history book.

Born to Run: My story by Cathy Freeman (Puffin, 2007)

The inspirational story of a national hero’s Olympic Gold dream.

Grace Beside Me by Sue McPherson (Magabala, 2012)

A quirky and warm teenage story about home and family life in a small town.

Maralinga: The Anangu story by the Yalata and Oak Valley community members and Christobel Mattingley (A & U Children, 2009)

The true story of the Anangu people before and after the British Government carried out seven nuclear bomb tests in Maralinga between 1956 and 1963.

Young adult

Songspirals: Sharing women’s wisdom of Country through songlines by Gay’wu Group of Women (Allen & Unwin, 2019)

A special Yolngu introduction to women’s songlines, connection to Country and landscape.

Welcome to Country: An introduction to our First Peoples for young Australians by Marcia Langton (Hardie Grant Travel, 2019)

An introduction to our First Peoples and a travel and historical guide to Indigenous Australia.

My Father’s Shadow by Jannali Jones (Magabala, 2019)

A family thriller set in the Blue Mountains by one of the 2015 black&write! Indigenous Writing Fellowship winners.

Growing Up Aboriginal in Australia, edited by Anita Heiss (Black Inc., 2018)

A diverse range of short memoir pieces from writers young and old.

Black Cockatoo by Carl Merrison and Hakea Hustler (Magabala, 2018)

A young Aboriginal girl called Mia discovers the relationship between family and culture.

Defying the Enemy Within by Joe Williams (ABC Books, 2018)

The former NRL player talks candidly about his battle with mental health and his inspiring road to recovery.

Ghost Bird by Lisa Fuller (UQP, 2019)

An original, spooky, action-packed and beautifully written story of two sisters.

Share article

More from author

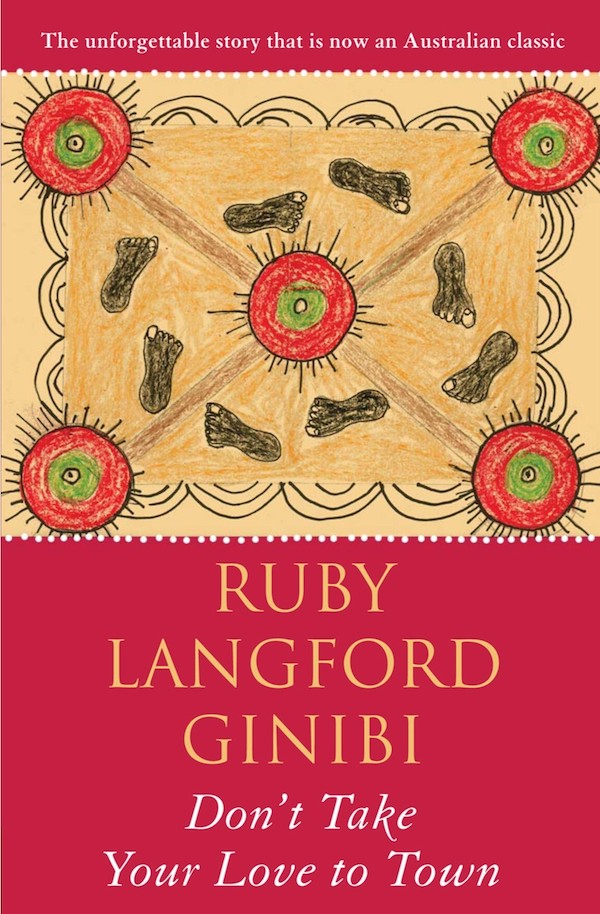

On ‘Don’t Take Your Love to Town’, by Ruby Langford Ginibi

N 1988, DON’T Take Your Love to Town became the first of five autobiographies that Ruby Langford Ginibi would have published during her almost thirty-year career as a writer, Aboriginal historian, activist and lecturer. Indeed it was this first book, her life story covering five generations of familial bonds, written in what would become her trademark conversational style, which would have a historic impression on Indigenous literature in Australia.

More from this edition

Orison

PoetryThree days later, we bought a Newton’s cradle. Put it on the table, and heartsick, tried to click click click our way out of it. But there are...

Q&A

Poetry[What are some common sources of light?] And, can light survive exposure to extreme temperatures? These are both questions we are interested in. Our goal for...

Annah the Javanese

FictionPol drags the chair near, steps up onto it to hammer a nail into the wall above the mantelpiece. He squats to lift a painting of a woman seated in a rocking chair. As he attaches it to the wall, Annah steps back, enraptured by the languid lines of the woman, her black hair, her cinnamon skin, which is the same shade as Annah’s own. The woman’s dress is as red as a nutmeg’s lacy mace. Her bare foot reaches from beneath its folds.