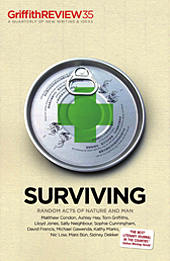

Featured in

- Published 20120306

- ISBN: 9781921922008

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

IN THE LEAD-UP to Christmas 2011 the usual mix of tension and excitement was underpinned by a new level of anxiety. This century the festive, holiday season has gained a new moniker in many parts of Australia: the disaster season. The geographic diversity of the island continent means that nature’s extremes take different forms, depending on latitude, longitude and patterns of settlement – fires for some, floods and cyclones for others, elsewhere earthquakes and storm surges or the lingering, prodding fingers of drought.

The summer of 2011-12 announced its arrival in a fiery fury in the Margaret River region of Western Australia. Dozens of homes collapsed into ash under the wind-driven force of flame and, as if to underline nature’s great levelling, even one of the oldest and best-tended mansions in the region, a house that had withstood a century and a half of extreme weather, was destroyed.

On the other side of the continent Queenslanders scarcely needed the Bureau of Meteorology to tell them that another wet summer loomed. The blue skies of travel ads were again crowded with heavy clouds; the blessing of some of the coolest days on record tempered the early summer heat. For the state’s many residents who depend on tourism the old slogan, ‘Beautiful one day, perfect the next’, and the rainy day money-back guarantee – which had once turned the ravages of drought into a marketing advantage – mocked cruelly.

At countless Christmas parties conversations about the legacy of the floods were impossible to avoid. Huge billboards entreated drivers of even the most robust four-wheel drives not to use flooded roads; high-rotation radio announcements reminded listeners to update their insurance, prepare their property and evacuation plans, keep provisions and a battery-powered radio (trannie) close to hand.

For the one in four Australians glued to their smartphones a government-created DisasterWatch app provided a ready reckoner of the range of catastrophe stalking the countryside at any minute – and a quick action guide for people and pets in the event of cyclone, earthquake, flood, lightning, storm or tsunami (not fire).

MANAGING DISASTERS HAS taken on a new political urgency here, as in many other countries. The apparent increase in the frequency and severity of random acts of nature, and the immediate and vicarious experience of them through wall-to-wall coverage, has changed the implicit contract between elected officials and the public. The Bush administration’s inept handling of Hurricane Katrina has become a talisman of sorts – in the age of instant communication few leaders, in developed or developing countries, would willingly risk similar opprobrium.

This is not a modern phenomenon; regimes have often collapsed as a result of catastrophic acts of nature, but the pace is now quicker, the urgency greater and the level of expectation – of what can and will be done – higher. It was hard not to feel sorry for the short-lived Japanese Prime Minister, despite his light-blue emergency overalls, failing to show the leadership that country desperately needed in the shocking aftermath of the tsunami, or to be impressed by the New Zealand Prime Minister and Christchurch Mayor as they spoke with calm assurance and compassion to bring some sense of order to earthquake-ravaged Christchurch, or by the Queensland Premier’s compassionate and resolute evocation of the intrepid spirit of Queenslanders.

Then, in August 2011, in what seemed from afar like American over-reaction, much of the United States stopped: metropolises were evacuated as Hurricane Irene taunted the Atlantic Coast. Intrepid reporters and camera operators ventured out, shouting somewhat pathetically into their microphones as water lapped seawalls of the seven emergency-declared states – while those less in awe of nature’s thrall held hurricane parties behind gaffer-taped windows and sandbagged doors.

For a few days much of the world was transfixed. A disaster foretold and broadcast live on television closes the gap between the vicarious fear Hollywood has taught us to enjoy and real threat and suffering, especially with a telegenic president taking control, pointing at maps and looking authoritative in an appropriately windblown way. The subsequent loss and damage was considerable, but on the scale of global disasters so far this century it is unlikely that Hurricane Irene will make the top ten.

IT IS WIDELY predicted that as the world becomes more populous and the effects of climate change become more manifest, natural disasters will increase in frequency and severity. The implications for domestic, regional and global political leadership will become clearer in coming years. The global architecture to cope and manage, to help put places and communities back together again, is far from resolved and this is likely to be one of the big projects of the next few decades.

Quite rightly, managing a disaster response is never easy. Finding the balance – between quickly getting things back to normal and ensuring that the lessons are learnt that will mean the next event is not as catastrophic – is costly and challenging. Fixing the manmade environment, getting things back to normal, is crucial but just the first step. The desire to quickly remove debris and begin to rebuild is an essential part of the recovery process, yet the expectation needs to be tempered by consultation that ensures history is not repeated, and the knowledge that the human impact will linger long after the last bit of rubbish has been removed.

Random acts of nature and man occur chaotically, with unintended and unpredictable consequences unravelling the cloak of certainty. In the midst of such events no one has perfect knowledge; even those at the control centre are responding to information as it becomes available and predictions that are only as good as the information fed into the current modelling. Intuition, judgement and experience also matter. This is why contemporaneous inquiries that seek to recreate events and sequences across widely dispersed areas are such important tools of understanding and learning – they help explain what happened and suggest steps that may obviate the worst in future.

In frustration and anger, some may hope that these investigations will shine a laser light on the guilty person, who can be named and blamed. That is rare. Blame may provide some comfort, but is rarely simply ascribed. It also suggests a degree of hubris out of kilter with the scale of the disasters that are already characterising this century. People and institutions can do things better, can learn lessons, can work out how to better respond and predict; but the balance between people and nature is not equally weighted and, despite our conceits, is unlikely to ever be so.

Still, one way or another most of us survive. As the central character in Julian Barnes’s Booker-winning novel,The Sense of an Ending (Jonathan Cape, 2011), notes: ‘I survived. “He survived to tell the tale” – that’s what people say, don’t they? History isn’t the lies of the victors as I once glibly assured Old Joe Hunt; I know that now. It’s more the memories of the survivors, most of whom are neither victorious nor defeated.’

As Griffith REVIEW enters its tenth year, this edition is a tribute to those who have survived random and catastrophic acts of man and nature – and those who through no fault of their own succumbed, and need to be remembered.

9 December 2011

Share article

More from author

Move very fast and break many things

EssayWHEN FACEBOOK TURNED ten in 2014, Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and nerdish face of the social network, announced that its motto would cease to...

More from this edition

The language of catastrophe

EssayTHERE ARE ENOUGH Black days in modern Australian history to fill up a week several times over – Black Sundays, Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays...

Surviving peace

GR Online‘We should kill our pasts with each passing day. Blot them out, so that they will not hurt. Each present day could thus be...

Ground cover

GR OnlineTHAT WAS THE day the garbage didn't get picked up, and the day the house across the road burned down. Trish, whose flat shared...