Featured in

- Published 20240507

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-95-5

- Extent: 203pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Revolutionary wave

Non-fictionThis was the late ’60s, early ’70s and surfing in Wales was regarded by the parent generation as delinquency. It was for losers, layabouts, rogue males. In those early days Welsh surfers numbered around one hundred, congregated on half a dozen beaches down fifteen miles of coastline west of Swansea, known as the Gower. I knew each one of those surfers by the styles they deployed on the waves. So idiosyncratic was early Welsh surfing that out on the road if you saw a car with boards on the roof coming at you, both drivers would pull over for a chat.

More from this edition

The comfort of objects

In Conversation Anne Zahalka has been making viewers look twice for nearly four decades. One of Australia’s most respected photo-media artists, her practice explores shifting notions...

Intimacies, intricacies, cadences

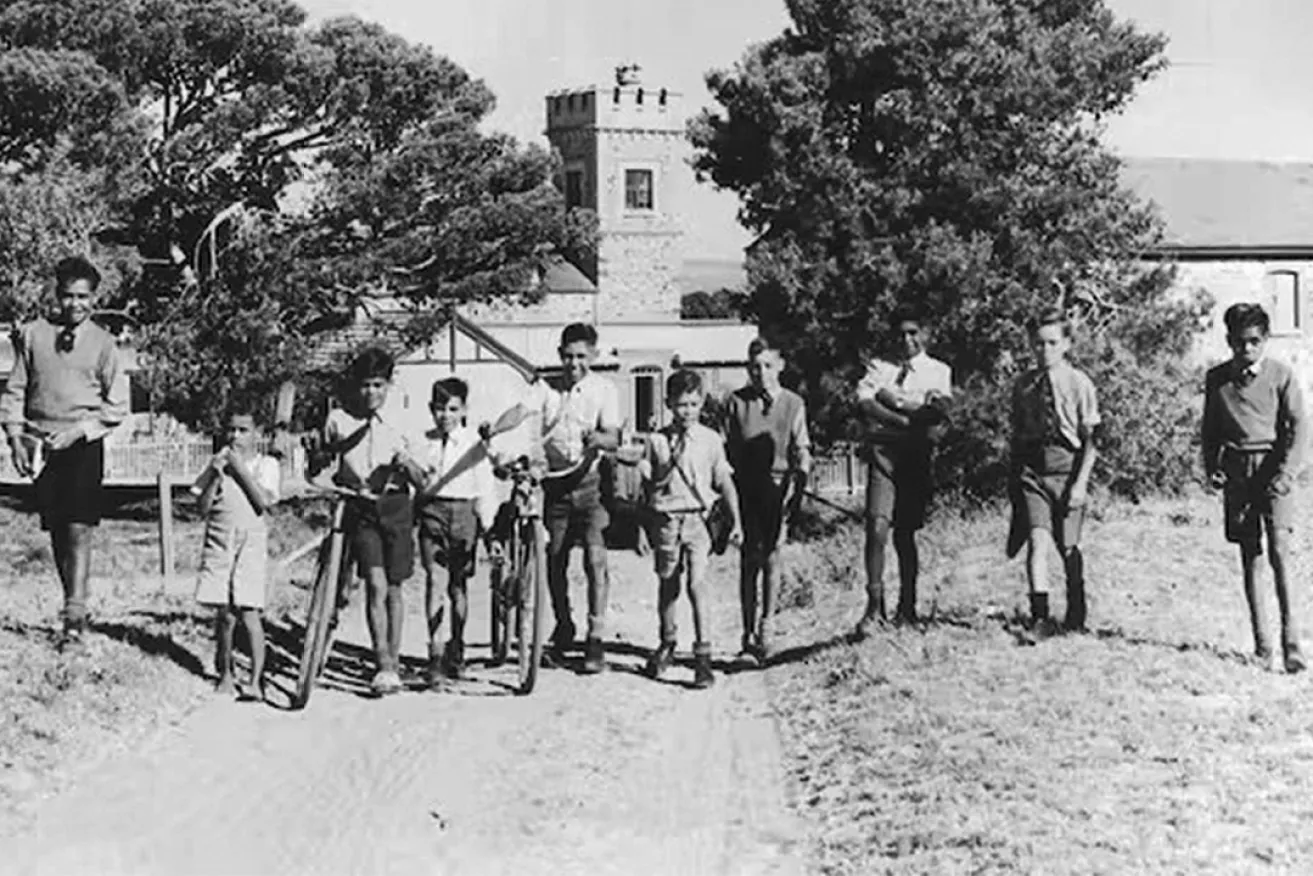

Non-fictionOver cups of tea, Vince was soon telling me stories. About his grandfather, his Ngadjuri heritage, the Aboriginal boys’ home he’d lived in for seven years, a small town called Curramulka where he’d captained and coached the local Australian Rules football team. He also told a story, in passing, about how his mum had to hide him from welfare after his dad died, when Vince was a small child.

Past-making within the present

In ConversationThe Marranbarna Dreaming story is a central story to Gudanji, and that essential story forms our beingness. My kids grew up hearing that story from when they were tiny babies – they heard it through my words and they heard it through the words of their grannies, so they could embed the story within their own sense of identity and then retell it. Both of my girls are mums now, and they retell that story to their daughters all the time, so it just becomes a normal part of who and how they are as Gudanji people.