Featured in

- Published 20230502

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-83-2

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Dave Witty

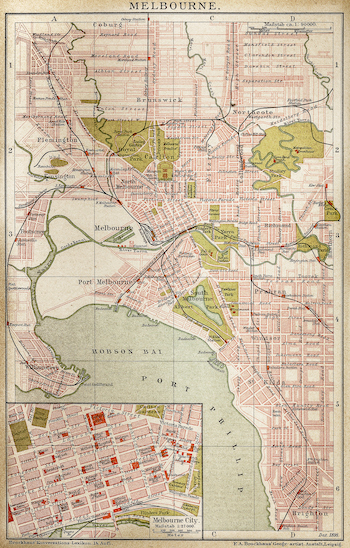

Dave Witty is a Melbourne-based writer. His first book, What The Trees See, will be published in 2023 by Monash University Publishing. His work has...

More from this edition

To sing, to say

Non-fictionHow poetry works – its oracular way, its indirection – is how land works, he saw. Land as a teacher, as an embodiment not only of its own intergrity but of human aspirations and virtues like hope and beauty; land as an educator of the senses; land as a measure against which to prove and compare one’s own and others’ lives, as a theatre for the divine comedy of all human life; land as an elder, as a god, as a library...

Rare

PoetryThere are many ways to carry a story. My father smothered his stories with bravado. Here he is, laughing at the sea drenching him on the deck.

Everybody loves beginnings

Non-fictionBeginnings are a breaking of silence that give some indication as to why the silence ought to have been broken, and the prospects of such a breaking. Why should I have broken my silence and begun this discourse? And why should the difficulties of breaking this silence, difficulties that for some reason I must enact in order to ameliorate, appear so manifestly predictable to me?