Featured in

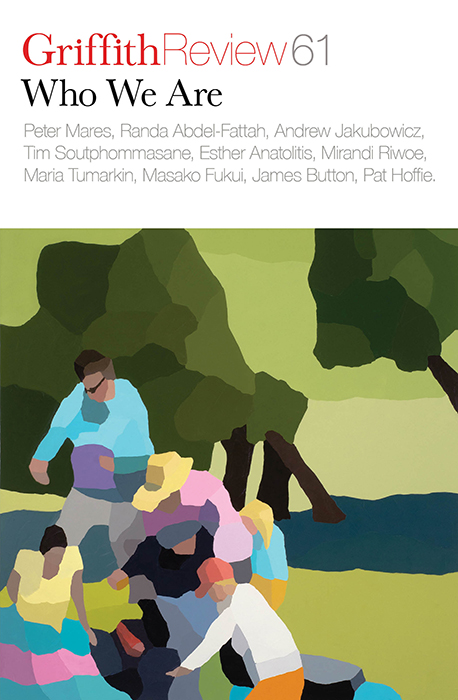

- Published 20180501

- ISBN: 9781925603323

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

Resisting the ‘Content Mindset’

Artists’ dedication to their practice has long been glamourised as the ‘struggling artist’ trope, trivialising the mental and physical labour of creative work. Their flexibility has been co-opted into the ‘portfolio career’, normalising all professional engagements that lack secure tenure, not just creative roles. Their agility in working cross-discipline and cross-platform has vindicated the expedience of a ‘content-first’ approach. Their precariousness has been hyped as the ‘gig economy’, standardising working conditions that lack basic entitlements. Their intellectual property has been stolen to feed or ‘train’ generative AI programs, making IP theft widely acceptable. (You’ve got to hand it to the Content Mindset’s PR guys: rebranding industrial-scale IP theft as ‘training’ for ‘artificial intelligence’ is right up there with rebranding creationism as ‘intelligent design’.) Artists’ venturous thinking is widely dismissed as ‘fringe’, depoliticising its impact. Time and again, artists’ commitments to their ethics and responsibility to their communities have been co-opted as ‘culture war’ tools, dumbing down the public debate to reinforce hegemonies. And of course, their works have been belittled as mere ‘content’, undermining their expertise.

More from this edition

Race and representation

EssayLIKE THE MEMBERS of every nation, Australians have fairly stable ideas about the kind of people we are, to the point of there being...

Sentenced to discrimination

EssayON AUSTRALIA DAY in 2016, artist Elizabeth Close was at an Adelaide shopping centre speaking to her young daughter in Pitjantjatjara, when a woman...

Three poems: A hard name, Chameleons, Damaged

PoetryA hard name There were reds under the beds when we were growing up and someone at school always ridiculed my name the name of the woman spy frozen in...