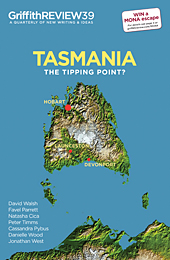

Featured in

- Published 20130305

- ISBN: 9781922079961

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

PROFESSOR JONATHAN WEST has a powerful intellect and an unquestionable passion for Tasmania. His work has driven and inspired many members of the Tasmanian community to rethink how we do things in Tasmania and how we might build a prosperous, innovative and inclusive future for our island state. West is an advocate for our island reaching its undoubted potential sooner, rather than later. His contribution to the state’s Innovation Strategy has been seen by many as a turning point in the economic and social direction of this state.

In my view, West’s contributions over the years have been written to provoke and inspire Tasmanians to think and do better. They have also challenged people from afar to view Tasmania with fresh eyes, to see the promise that this island holds. This is exactly the kind of debate that a mature and confident community is not only comfortable with but actively encourages.

Unfortunately, aspects of West’s essay in Griffith REVIEW 39 are disappointingly negative and out of step with what is actually happening in Tasmania, with the community that we are and the journey we are on – a journey that West himself has been heavily involved in. He fails to recognise many of the changes within the Tasmanian economy that have occurred over the past two years, and the work done by government, the community and the private sector to drive those changes. Instead of inspiring us and engaging others, it contributes to grinding down an emerging confidence. For some locals it confirms our sense of mediocrity and for others it triggers the ‘Ah well, I told you so’ moment.

I do dispute the validity of some of the claims in West’s essay. For example, when describing Tasmania’s ‘highest petty crime’, he fails to mention that in most national crime indicators, Tasmania ranks about the same as Victoria and New South Wales, while crime clearance rates – the number of crimes solved – are consistently and significantly higher in Tasmania than the national average. West’s analysis is correct in many respects, however, especially in his presentation of the stark data concerning our health and educational outcomes. He is also right to say there are groups in our community that, with little or no consequence from their actions, voice opposition to developments that are socially and environmentally sustainable and that would create economic prosperity. But does this not happen across the world? Are we the only community that sees this contest of ideas, and this struggle for how a place is developed? It is because of our relative size and proximity to each other that these battles are played out far more ferociously and with, at times, more obvious and immediate consequences.

LET’S PUT THINGS in perspective. We are an island state of half a million people, equally dispersed from the top to the bottom (with three distinct sub regions). This places enormous pressure on the delivery of social services. We are also economically and geographically isolated from our broader region and our markets, and we live in a first-world country with high living standards and associated expectations.

Like many communities, Tasmania has many layers and much complexity. Yet because we are a state in its entirety, our data is very accessible and easy to interrogate – unlike other Australian states that are able to aggregate statistics and therefore mask areas of disadvantage, for instance in regions as opposed to cities. Tasmania is also characterised by dichotomy. We have pockets of wealth and pockets of disadvantage. We have moments of breathtaking absurdity and incompetence, but we also enjoy moments of brilliance and inspiration that are truly stunning, setting this place above and apart from any other.

We have the highest proportion of scientists and researchers of any state in Australia. We are Australia’s gateway to Antarctica, with the highest proportion of Antarctic and Southern Ocean researchers of all of the five international gateway cities. Our science and research sector is world-class. We have the highest proportion of artists and our attendance at cultural events is the highest of any Australian state. We have one of the finest museums in the world in MONA: some say this is the first truly Australian museum in its irreverence and complexity, showing no regard or respect for the conventions of the art world. We also look forward to the establishment of another of the state’s most ambitious cultural sector projects – the University of Tasmania’s $75 million Academy of Creative Industries and Performing Arts, based on a site next to the Theatre Royal in Hobart’s CBD and utilising National Broadband Network technology to connect across Tasmania. Across the next seven years, this project promises to attract up to 3000 new students and has the potential to generate more than $660 million in direct and indirect economic benefits.

For many years Tasmania was seen by many as a place of mediocrity, across social and economic indicators. Special things happened elsewhere. It was accepted that if you wanted to achieve or to ‘make it’ you had to leave. This is a generalisation, however. As with many generalisations it glosses over many remarkable success stories and the individuals behind them – Claudio Alcorso, Joseph Chromy, the Flanagans (all of them), Rodney Croome, Robert Clifford, Dale Elphinstone, Kim Seagram, David Walsh, Brett Torossi, Rob Pennicott and many others.

But something significant has changed in Tasmania across the past decade. A new and increasingly intoxicating mix of creativity, innovation and self-confidence has emerged. This has been given an extra push by people new to Tasmania (and therefore not constrained by the baggage of history) and a critical mass of returning members of the Tasmanian diaspora who have travelled and worked the world, now coming home as they realise how special Tasmania is. This has helped us to lift our heads, collectively, as a community. We no longer expect or accept mediocrity. The Tasmanian community is also one that today celebrates our diversity and is more inclusive than many.

So, to the economy. Following the Victorian gold rush in the Nineteenth century, Tasmania’s economy relied heavily on exporting of a few commodities, many of them low value. As the Twentieth century progressed, these in turn relied on the low value of the Australian dollar to compete in international markets.

Now we have entered the second decade of the Twenty-first century. The global financial crisis and strength of the Australian dollar – now widely accepted as a structural change rather than a cyclical one – have dramatically impacted on Tasmania’s terms of trade. We have seen a fundamental shift in our economy, the extent and comprehension of which was masked by the federal and state governments’ stimulus package between 2008 and 2010, which pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into our economy. For a period during 2010, Tasmania had the lowest unemployment rate in Australia, at a time that Australia had the lowest unemployment rate in the world. But that stimulus is gone. The challenge of our economic transition is in full view, and our unemployment rate of over 7 per cent is the highest in the country.

A transition is occurring to a more diverse, innovative economy producing highly value-added products and building on the liveability advantages Tasmania provides. The change in our terms of trade has meant that this transition is now progressing rapidly. This places enormous pressure not only on our traditional industries but also our growing and emerging industries.

Tasmania must play to its strengths. Our products need to be highly value-added to address issues of freight and labour costs. Tasmanians must be innovative to secure position in increasingly competitive global markets.

We have natural advantages due to our climate and our environment, our abundance of water and other natural resources, and our people who are increasingly being recognised as innovative and passionate. We will soon have access across Tasmania to high-speed broadband through the National Broadband Network, a key piece of infrastructure that combats the tyranny of distance. If you don’t need to live or conduct your business in a specific place, why wouldn’t you do it in this place – which consistently rates highly on global liveability measures? While some see our future as dark and bleak, nothing could be further from the truth. We are indeed at the tipping point: this is our moment, our time. But we can easily miss that opportunity if we fail to drive these advantages home or we look to others for remedies.

There are many examples of individuals and businesses who want to relocate, startup or expand their investment here – in sectors from agriculture to IT – to take advantage of what Tasmania has to offer. West’s description of his report prepared through the Australian Innovation Research Centre at the University of Tasmania for the federal Department of Regional Development rightly identifies the many positive opportunities for growth in the Tasmanian economy. When West began this research in August 2011, these had already been identified in the Tasmanian Government’s Economic Development Plan – launched that same month. That plan provided a comprehensive, whole-of-government framework for economic growth, listing the ten key sectors for a strong economic future: Antarctic research and supply; building and construction; food and agriculture; forestry; ICT; mining; renewable energy; science and research; specialist and marine manufacturing; and tourism. Work immediately began on three Regional Economic Development Plans which provide the most detailed analysis yet undertaken of Tasmania’s three regions, linking their respective and diverse strengths to the economic activities that would best transition them into a prosperous future. Given that this detailed and strategic economic work has been a key focus of the current Tasmanian Labor Government for the past several years, I was disappointed to read West’s assertion that ‘government tends not to act and the obstacles remain.’

There have been remarkable achievements in the past few years in the very areas that West identifies as the solutions to Tasmania’s economy, and in which he asserts that no progress has been made. Major new investments in the dairy sector have included Fonterra’s $6 million expansion at Spreyton and $12 million upgrade of its Wynyard cheese plant, Lion’s $150 million redevelopment of its Burnie and King Island specialty cheese plants, Tasmanian Dairy Products’ $70 million milk powder plant in Circular Head, Tamar Valley Dairy’s $10.6 million purpose-built yoghurt manufacturing facility and Ashgrove Cheese’s $5 million expansion at Elizabeth Town. The Van Diemens Land Company is close to finalising its $180 million dairy farm expansion at Woolnorth. All of these dairy projects – and other agricultural expansion – is underpinned by the government’s $400 million irrigation expansion program which has four schemes completed, construction of the $104 million Midlands and $15 million Lower South Esk schemes recently started, a seventh scheme at Forth ready to go, and business cases for a further six proposed schemes being prepared.

In aquaculture, the multimillion-dollar joint venture between Tassal, Huon Aquaculture and Petuna Seafoods will double production in Macquarie Harbour, an $8.5 million investment will boost production in the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, and Skretting Australia’s new $36 million fish feed plant at Cambridge demonstrates confidence in the Tasmanian salmon industry’s growth prospects. Tasmania’s wine industry has received accolades across the world following Hobart hosting the eighth International Cool Climate Wine Symposium last year, including being ranked second only to China as the most desirable place for investment in this sector in the world. Investment growth has accompanied this profile with major investments from renowned companies including Brown Brothers and Shaw and Smith. There are more examples, but you get the picture.

KEY CHALLENGES FACE Tasmania in education and health. We must do better, which is why we have invested in child and family health centres in the areas of greatest need; and in early childhood education, which is already making a difference with the ‘launching into learning’ and ‘bridge the gap’ programs. But we must do more. That is why education sits on the Economic Development subcommittee of Cabinet. As part of a strategic and whole-of-government approach we recognise that education – intertwined with industry and community economic development – is the key to unlocking Tasmania’s future prosperity.

We have a five-year window to get this right. The Age newspaper recently referred to Tasmania as the ‘new black.’ People offshore are interested, but every fashion has a shelf life. The current Tasmanian government has a clear vision, but the short-term focus of the political cycle could soon undo the work that has been done. Our challenge is to embed sustainable and lasting transformation, and to inspire this community.

It will take community, industry and political leadership working together to deliver this. Tipping point – yes, it is. Basket case – no, we are not. Would you rather be anywhere else? Not on your life!

Share article

About the author

David O’Byrne

David O'Byrne was elected to the Tasmanian Parliament as the Member for the electorate of Franklin at the 2010 State election.He is the Tasmanian...

More from this edition

Putting the science in the shed

GR OnlineTHE INSTITUTE FOR Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), which has brought together scientific leaders from a variety of fields at the University of Tasmania...

Assuming the mantle

EssayON THE MORNING I visit Ancanthe, a billowing veil of rain is drifting off the mountain, reducing the trees to downy silhouettes. Then, just...

Tasmanian gothic

EssaySOME DARK SECRETS run so deep that they slip from view. The hole left in our collective conscience is gradually plugged, with shallow distractions...