Featured in

- Published 20031202

- ISBN: 9780733313509

- Extent: 236 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm)

THE EVIDENCE IS clear. The way we are living is not sustainable. In fact, I believe it does not satisfy any of the main criteria. We are using resources future generations will need, damaging environmental systems, reducing social stability and increasing the gap between rich and poor. Further, there is no prospect of extending the lifestyle of the wealthy world to developing countries. People in the poorer parts of the world are constantly reminded through film and television of the widening gulf between their material deprivation and the wasteful consumption of the rich.

If civilisation is to survive, there must be a dramatic transformation in technological capacity, in social institutions and in values: our approach to the natural world and to each other. Both at the local and the global level, some of us still believe we can achieve a transition to a sustainable future. Human systems can change radically almost overnight. Growing recognition of the need for radical change may produce the changes. The serious obstacle is the dominant mind-set of decision-makers who do not even recognise the problems and see potential solutions as threatening their short-term interests.

A series of publications has documented the scale and seriousness of environmental problems. At the national level, two Federal Government State of the Environment reports have now been published. The 1996 report showed that we had a beautiful and unique environment, many aspects of which were in good condition by international standards, but some very serious problems, most obviously, loss of biological diversity, degradation of inland waterways and destruction of the productive capacity of rural land. Its final section linked the environmental problems to lifestyle choices, showing that the goal of sustainability will require integrating environmental awareness into all social and economic decisions.

The 2001 State of the Environment report, released last year, notes an improvement in urban air quality but finds that all the other critical environmental problems are getting worse because the pressures on natural systems are still increasing. Each year the Australian population grows by about 200,000, as the excess of births over deaths [about 120,000] is augmented by net inwards migration. The material expectations of people also increase; we use more energy, travel further in larger and less-efficient cars, consume more resources and produce more waste. The compounding effect of more people, each on average demanding more, is putting greater pressure on natural systems.

The decline was confirmed in 2002 when the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its report Measuring Australia’s Progress. During the decade 1990-2000 all of the usual economic indicators showed positive trends. The social indicators were mixed, with some worrying negative trends. Of the environmental indicators chosen, only urban air quality improved. More land was cleared, more species threatened, river health declined, more land was degraded and greenhouse-gas emissions increased. The increasing economic production from the natural systems of Australia is coming at an environmental cost. Tim Flannery made this point about the unsustainable use of Australia’s natural resources in his book The Future Eaters, conjuring the image of the present generation consuming the opportunities of future generations by our lifestyle choices.

Global studies draw the same conclusion. The United Nations Environment Programme has now produced three reports in its Global Environmental Outlook (GEO) series. They show some successes, such as the concerted international effort to curb emissions of chemicals that deplete the ozone layer and “encouraging reductions in many countries” of urban air pollution. They also document “environmental challenges” – increasing emissions of greenhouse gases, over-exploitation of water, 1200 million people without clean drinking water and twice that number without sanitation, species being lost at an increasing rate, fisheries in decline, land degradation and problems caused by increased fixing of nitrogen for agriculture.

The science drawn together in a report by the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure paints a disturbing picture. Human activities are affecting global systems “in complex, interactive and apparently accelerating ways”. We now have the capacity to alter natural systems in ways “that threaten the very processes and components … on which the human species depends”.

SO HOW CAN we achieve a sustainable future? We certainly need to move beyond the simplistic view that economic growth will solve our problems. The report Our Common Future by the World Commission of Environment and Development shows the main causes of environmental degradation are poverty in poor countries and unsustainable consumption in wealthier countries. The first of these problems can be reduced by economic growth but the second is exacerbated by growth. As Clive Hamilton shows in his recent book Growth Fetish, in societies like ours where most people have all the essentials of a decent life and more, growth does not make people happier or more fulfilled and has social and environmental costs.

Dovers and Wild River argue in Managing Australia’s Environment that effective environmental policies have five characteristics: persistence, purposefulness, flexibility, inclusiveness and sensitivity or information-richness. This helpful metric extends the argument in the 1996 State of the Environment report that successful remedies for environmental problems take a comprehensive and systematic approach, whereas failures are usually piecemeal efforts that attack symptoms rather than underlying causes.

Since some of the underlying causes are related to lifestyle choices, those choices must be considered. In Resetting the Compass, Yencken and Wilkinson suggest a guide for “Australia’s journey towards sustainability”. After summarising our environmental problems, they argue existing policies will not achieve a transition to sustainability because they do not address the growing pressures: increasing population and increasing material demands per person. They conclude we need a population policy and a commitment to “dematerialisation”, citing a German study that argues that Europe could reduce energy use by a factor of four and materials use by a factor of 10 – and noting that several European nations have adopted those targets. They support development of a real progress indicator, as the gross domestic product doesn’t measure wellbeing. More generally, they argue that sustainability’s four dimensions – economic, social, cultural and ecological – deserve equal attention. Along with Hamilton, they note that growth has costs as well as benefits and argue that we should pay more attention to the quality of growth than to the rate. I agree, but I add a fifth dimension: resources. In the medium term, access to petroleum fuels may be a crucial barrier to sustainability.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL level, there has been a growing awareness that a sustainable future will involve significant change. Our Common Future says that the world’s economic and environmental futures are intertwined and should be seen as complementary, rather than in competition. GEO2000 notes that the present course is unsustainable, so doing nothing is no longer an option. GEO3 sets out some of the principles for change by exploring four possible scenarios. The approach is taken a step further in the report by the Global Scenario Group, Great Transition. The report examines six possible futures: two conventional approaches, named as Market Forces and Policy Reform; two pessimistic futures, Fortress World and Breakdown; and two types of Great Transition, called Eco-communalism and New Sustainability. It says: “The scenarios are distinguished by distinct responses to the social and environmental challenges. Market Forces relies on the self-correcting logic of competitive markets. Policy Reform depends on government action to seek a sustainable future. In Fortress World it falls to the armed forces to impose order, protect the environment and prevent a collapse into Breakdown. Great Transitions envisage a sustainable and desirable future emerging from new values, a revised model of development and the engagement of civil society.”

The report concludes that the Market Forces scenario cannot lead to a sustainable future because a combination of factors such as widening inequity and environmental degradation will undermine the social cohesion and international stability needed for the operation of orderly markets. The most likely result would be a slide toward a barbaric future, either Fortress World, in which an elite is able to protect its lifestyle by armed force against a growing insurgency of the disadvantaged, or a Breakdown, with loss of the support systems needed for a civilised life. Great changes can in principle be made by a Policy Reform approach, which could dramatically cut resource demands and environmental consequences of our lifestyle.

THE PROBLEM IS thta the political will to impliment such a strategy is not in sight. Under the Hawke government, nine working groups developed approaches that would bring both economic and environmental benefits to major sectors of the Australian economy. Twelve years later, the consensus recommendations in the National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development still gather dust. As Great Transition says, Policy Reform has to overcome “the resistance of special interests, the myopia of narrow outlooks and the inertia of complacency”. As long as politicians are more concerned about the next election than the next generation, the necessary reforms won’t happen.

The Great Transition recognises that market-led wealth generation and government-led technological change need to be supplemented and guided by a values-led move to an alternative global vision, based around such principles as equity. We can’t be secure or comfortable continuing to do property deals from our cars on mobile phones in a world where the majority of people have never made a telephone call, ridden in a car or owned any property. The report envisages the economy as a means of serving our needs within the limits of natural systems, rather than as an end in itself. It assumes a technological transition based on the principles of renewable resources, efficient use and “industrial ecology” – using the waste of one process as the input to another. It sees hunger eliminated by population stability and improved distribution systems to reduce waste. Above all, it sees a future form of genuine globalisation, rather than the present fad of reducing restraints governments place on corporations.

There is a sense in which the Great Transition is utopian but that has been said at the time of all the important reform movements. Those who opposed slavery 200 years ago were told that no economy could function without slave labour, while the suffragettes were persecuted when they demanded the vote for women a hundred years ago. Closer to our time, 20 years ago it was still utopian to be dreaming of Berlin without the Wall or South Africa without apartheid – or good coffee and civilised licensing laws in Queensland. Most of the social reforms we now take for granted were initially denounced as utopian. They happened because determined people worked for a better world. All around the globe, individuals and groups are striving to develop the social and institutional responses that will bring about the transition to a sustainable future. No amount of tinkering with environmental regulation or pollution-trading schemes will achieve the sustainable future our descendants deserve. We all have to change our values in fundamental ways. This is simply our moral duty to future generations, our own descendants.

Share article

More from author

A long half-life

EssayON MY DESK there sits a well-thumbed copy of the 1976 Fox Report, the first report of the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry. I grew up...

More from this edition

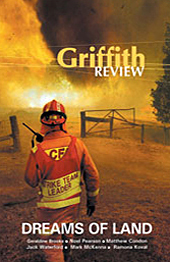

The land – dreams and disappointments

IntroductionTHERE ARE THREADS that run like arteries through a nation and in this country one is the land. It is the source of many...

The way we live

ReviewTHE SUBURBS HAVE always held an important place in the Australian imagination. The space between what Henry Lawson referred to as the "city proper"...

The painted desert

ReportageFITZROY CROSSING, IN north-western Australia, is a group of settlements set between abrupt scarps of sandstone. The weather oscillates between the furnace heat of...