Featured in

- Published 20210504

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-59-7

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Click here to listen to Editor Ashley Hay read her introduction ‘New vibrations’.

IN THE FIRST months of 2020, the vibrations of the Earth changed. As monitored by a global network of seismologists, the average daily displacement of the surface of the planet – measured in nanometres, or increments of one billionth of a metre – fell around the world, from Nepal to Barcelona to Brussels. In Enshi, in China’s Hubei province, and in New York City, average ground displacement fell to less than one nanometre from pre-pandemic levels of 3.25 nm and 1.75 nm respectively.

Life quarantined, life socially distanced, meant ‘the hum of daily life has quieted’, as National Geographic put it. Trying to curb the spread of the virus, Nature noted, ‘might mean that the planet itself is moving a little less’. That slowed-down quietude did not lead to quieter minds.

The pandemic has disrupted different lives in different ways. Day-to-day experience in Australia is a prime example of this compared with many other countries – 112 days of Melburnian lockdown notwithstanding. Yet there’s a universality to COVID-19, and the idea of such a collective experience manifesting a physical shape or impact at a planetary level is seductive, given the widespread occurrences of anxiety, of uncertainty, of disconnection, of loss of agency, of loneliness, of fear that have rippled around the globe.

On 18 March 2020, the World Health Organization’s report Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak noted that ‘a near-constant stream of news reports about an outbreak can cause anyone to feel anxious or distressed’. It concluded: ‘avoid listening to or following rumours that make you feel uncomfortable.’

Later that year, the media’s observations of, and predictions about, the virus’s impacts on mental health collided with the University of Oxford and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre’s finding that nearly one in five people diagnosed as Covid-positive were impacted by ‘a psychiatric disorder such as anxiety, depression or insomnia’ within the following three months, while people with a pre-existing mental health diagnosis were ‘65 per cent more likely to be diagnosed with COVID-19 than those without, even accounting for known risk factors such as age, sex, race and underlying physical conditions’. ‘This finding was unexpected and needs investigation,’ Dr Max Taquet from NIHR told The Guardian. ‘In the meantime, having a psychiatric disorder should be added to the list of risk factors for COVID-19.’

By March 2021, PubMed – the free search engine focused on biomedical and life sciences – listed nearly 250 new papers exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19: the bar chart tracking the explosion in this work shot up from its horizontal X-axis like a skyscraper. This research addressed the pandemic through a wide range of prisms, including loneliness, suicide prevention, air pollution and geriatric mental health, grief, schizophrenia, human–animal interactions and gambling. The first paper exploring ‘Chronic Zoom Syndrome’ appeared in Australasian Psychiatry on 5 October 2020.

All of which was overlaid on the world’s complex and extant map of mental illnesses and wellbeing like so many new clusters of fronts, troughs and weather systems on an already densely packed synoptic chart. The pandemic was, simultaneously, magnifying glass, incubator and accelerator for rapid change in the world’s collective mind.

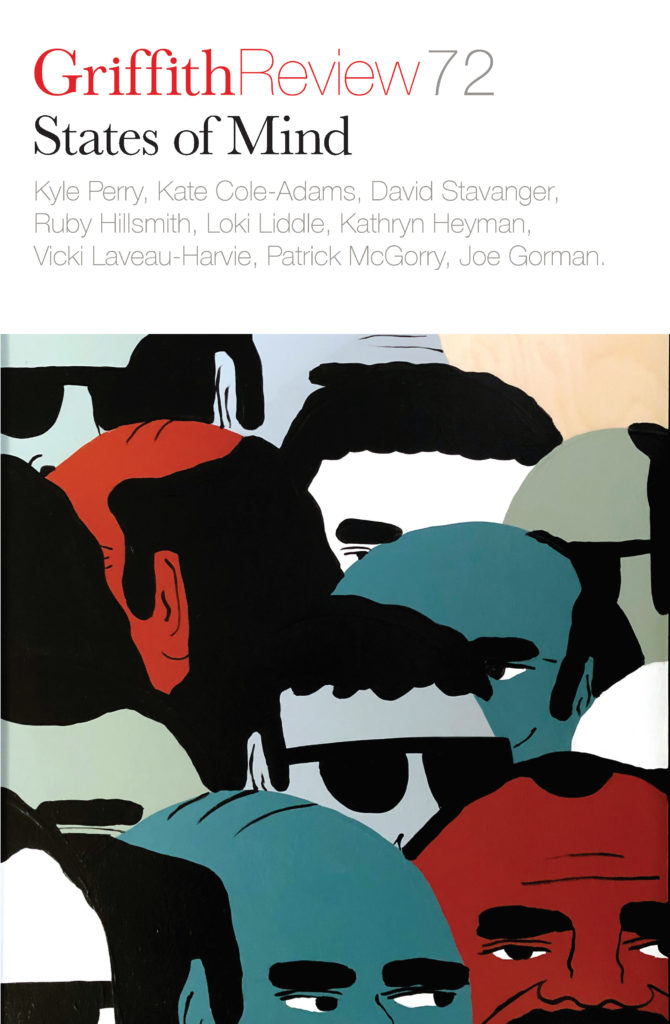

IT’S AN UNDERSTATEMENT to say that the phrases ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ operate as a kind of manageable shorthand for a vast and various range of human experience. The WHO constitution defines mental health as ‘more than just the absence of mental disorders or disabilities’, a quality ‘fundamental to our collective and individual ability as humans to think, emote, interact with each other, earn a living and enjoy life’ and ‘an integral and essential component of health’. The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition – or DSM-5 – lists nineteen categories of disorders, dysphoria and dysfunctions in its categories of diagnostic criteria and codes, including neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive disorders, depressive disorders, gender dysphoria, trauma- and stressor-related disorders, schizophrenia spectrum and various psychotic disorders. When Griffith Review 72: States of Mind set out to explore some of the contours of this landscape, it was inevitable that the current pandemic would overlay its topography. But there is more to this collection than the ongoing impacts of that novel coronavirus – psychologically unprecedented though they may be.

Along the collection’s spine are ranged a combination of essays exploring policy, pharmacy, psychiatry and psychology, beginning with a broad survey by Patrick McGorry, one of the country’s leading mental health researchers and advocates. McGorry’s generous distillation of knowledge delineates critical stratigraphies of illness, diagnosis and treatment while outlining the need for urgent reform across both policy and service delivery. Steven Kennedy, current Secretary to the Australian Treasury, reflects on his pre-economics training as a psychiatric nurse – an apposite background to have when responding to an unprecedented health crisis. Neeraj S Gill, a former acting Chief Psychiatrist of Queensland, explores the necessary intersections of mental health and human rights. Pat Dudgeon, the first registered Indigenous psychologist in Australia, joins with Dawn Darlaston-Jones and Joanna Alexi to celebrate the placement of an Indigenous framework at the heart of all Australian psychological curricula. And Kate Cole-Adams and Bianca Nogrady explore two new research frontlines, the psychedelic and the endocrinological.

Around these pillars are woven a suite of stunning narratives that spring differently from personal experience and reflection, including Lech Blaine’s transcendence of the accident that defined his late-teenage life, Ruby Hillsmith’s reports from the trenches of deep psychiatry and Beau Windon’s playful reframing of the pandemic’s recent history. Breakthrough crime author Kyle Perry counsels himself through the intertwined processes of living, working and writing. Tanmoy Goswami, the world’s first sanity correspondent, reflects on that journalistic round – and that label. Masako Fukui explores tensions between mental health and race and culture, Brooke Davis plumbs the crossovers of memory and long-held grief, and Vicki Laveau-Harvie sets off in search of the next chapter of her complicated family narrative. New fiction by Alex Miller and Gretchen Shirm – plus the first work by emerging Jabirr Jabirr writer Loki Liddle – interweave with a rich collection of poetry by writers including David Stavanger, A Frances Johnson and Mindy Gill.

Griffith Review received a record number of submissions for this edition – almost 550 – and this collection can only represent a small subset of the mental, emotional and practical ways in which people have experienced and navigated their world. Its selection is about variety and voice as much as securing a range of distinct and nuanced stories that may have taken a life’s work – or a life’s living – to finally arrive on the page.

Some of these stories are confronting; some invite readers into experiences that are very raw. Some are funny; some are hopeful; some despair. One quality that runs through and links them all is trust, an emotional and logical act that creates an opportunity for readers to meet narratives they might find personally familiar and narratives far beyond anywhere they have found themselves. We’re aware that some may be difficult to read – and suggestions for external support are given below.

IN MANY WAYS, questions of mental health have become one of the pandemic’s shared points or lightning rods, rendering this aspect of human existence more visible and more discussed. The pandemic has changed everyone, mentally, in some way. What is our aspiration for this space beyond where we are now? The world is maybe quieter, calmer, slower – more still, at least according to those diminished nanometre readings. It sounds like such a profound change, the alteration of the very movement of the Earth. And yet for something that operates across a planetary scale, it’s a change of which we’re not even really aware.

If the world is less mobile, the same cannot be said of many personal, internal worlds. And if there’s pleasure in a quieter mind, there’s pleasure, too, in more movement, as there is in the promise of moving – and moving more towards each other – again. In the meantime, words provide the most guaranteed means by which anyone can still travel.

Perhaps, through shared stories, through new ideas and research, we’ll notice more, and notice changes, when we can move and meet and talk again. Perhaps we’ll recognise our existential selves in a new way. Perhaps, more importantly, we’ll recognise one another – and the infinite complexities of our states of mind and being – differently too.

9 March 2020

This publication contains content some readers might find distressing. If this raises any concerns for you, help is available from Lifeline on 13 11 14 or at beyondblue.org.au

Share article

More from author

Between different worlds

IntroductionAntarctica offers windows into many different worlds...

More from this edition

The light we cannot see

PoetryI am the way into the city of woe, I am the way into eternal pain, I am the way to go among the lost. Dante Alighieri,...

Unease and disease

EssayOVER THE COURSE of eight years I researched and wrote a book, Bedlam at Botany Bay, about colonial madness in Australia. I read the records...

On surviving survivor’s guilt

Memoir MY MOTHER’S ASHES got scattered at the end of Australia’s Black Summer. She’d been dead for eighteen months. But her family – my five foster...