Featured in

- Published 20150203

- ISBN: 9781922182678

- Extent: 264 pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

More from author

We are all deaf during the pandemic

GR OnlineFor me, every day is an online conversation, with or without a pandemic. Sentences are broken. Loud noises interfere. There’s a lag as I try to decode what someone has said. I am permanently exhausted from the huge amount of processing my brain requires to function in the world.

More from this edition

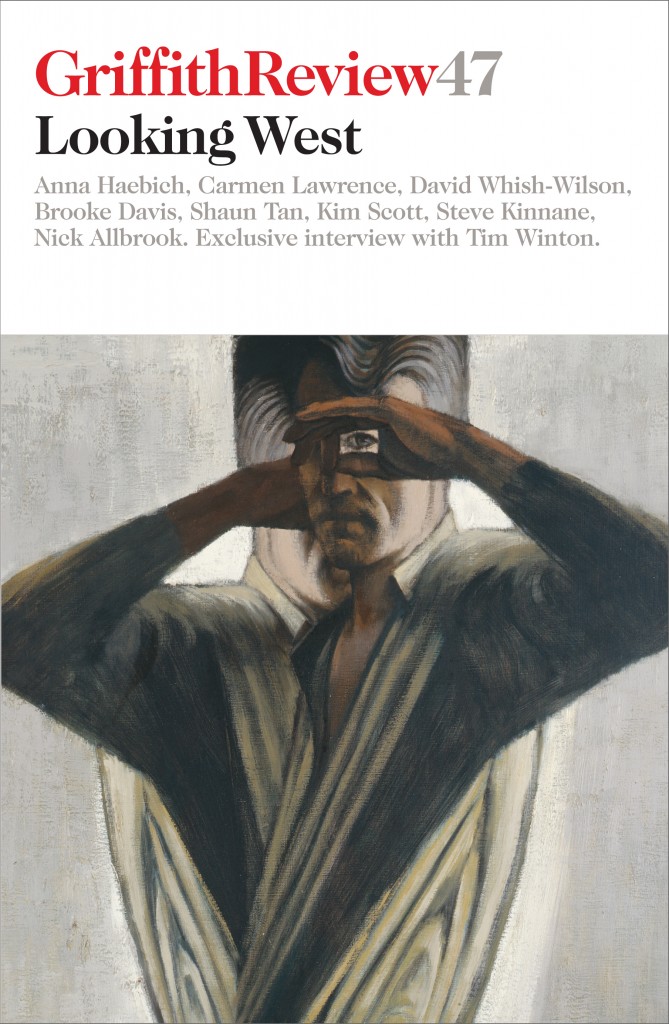

Shifting focus

EssayTHE TYRANNY OF myopia continues to skew the chronicle of Australian art history. According to Edmund Capon in his ABC series The Art of...

Land, glorious land

IntroductionIN THE BEGINNING it is about land: enjoying, aggregating, owning, using, preserving, developing and selling land. Land is, and always has been, a fulcrum of...

Swamp

GR OnlineUnder this site was a swampThe waters remainonly run deeper still– Plaque at Perth railway station A SMALL BOY is chasing a bird that is...