Featured in

The collage creations of California-based artist Moon Patrol take viewers into a kaleidoscopic time machine. He draws on the aesthetics of twentieth-century pulp illustrations, comic books, movie posters and more to craft his always alluring, sometimes unsettling artworks: visual fever-dreams populated by villains and vixens, monsters and mythic beings. He’s also the man behind the striking cover art of our latest edition. Griffith Review 83: Past Perfect features Moon Patrol’s Qhost Cowboy, which depicts a louche, gun-toting figure with a television for a head. In this interview, Moon Patrol talks to Editor Carody Culver about retro aesthetics, hidden identities and the stories we keep coming back to.

CARODY CULVER: You’re a self-taught artist. When did you first begin creating art, and what drew you to digital collage as a form?

MOON PATROL: I’ve always been interested in the collage aesthetic, but mostly through music or literature. William Burroughs’ cut-up technique, where a written text is cut up and rearranged to create a new text, was a big influence on me in my teens and early twenties. And even after I drifted away from Burroughs, his aesthetic stuck with me. One of his most resonant lines from The Soft Machine became my mantra long ago for my collage process: ‘So I am a public agent and don’t know who I work for, get my instructions from street signs, newspapers, and pieces of conversation I snap out of the air…’ Something about Burroughs sticks with you, like tree pitch or superglue, and once you’re infected with his vibe he’s hard to shake off. David Cronenberg once said something to that effect, that he had to force himself to stop reading Burroughs because Burroughs’ style was creeping into Cronenberg’s screenwriting.

As far as musical influences go, the turntablists and DJs of the ’80s, ’90s and 2000s – in particular Kid Koala – have been a big inspiration to me. I love Kid Koala’s playfulness and athleticism. Turntablism is a physical as well as cerebral art, and that energy and reliance on reflex is a huge inspiration to me.

CC: Can you talk me through the process of creating a collage? Do you have an idea at the start of what the final artwork will be, or is it a more open-ended process?

MP: I have a folder of 3,000-plus image files – all JPEGs – on my computer. These are images that I’ve scooped up from any old corner of the internet, or photos of book covers I take on my phone as I browse through used bookstores. I open up a new canvas on Photoshop, and I start putting things together, seeing what gets the train rolling. I usually don’t have a preconceived idea, so it’s sometimes a fraught process, and sometimes I step away a few hours later with nothing done and I’m frustrated. I used to think I had ideas in mind and assumed I’d just put the ideas together and produce a new piece – voila! So I’d open a new canvas and give it some title or another based on the assumption that I’d end up with whatever was on my mind. But then I’d end up with something so totally different, and it was impossible later to find old pieces on my hard drives because they would have totally unrelated titles. Now I just title new canvases WIP (work in progress), and then give them a title once I’m done.

There’s a huge amount of luck and discovery involved with the collage technique where – if it’s not reaching the randomness of aleatory music – it’s pretty darn close to genuine randomness and dumb luck. And because I don’t plan these pieces out before I start the process, the amount of surprise I often feel after completing one of these pieces speaks to a certain amount of luck and randomness inherent in the process.

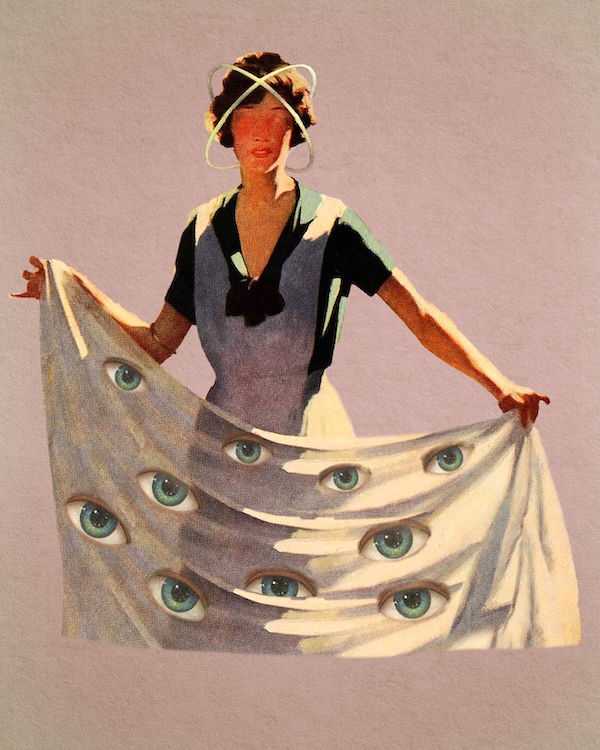

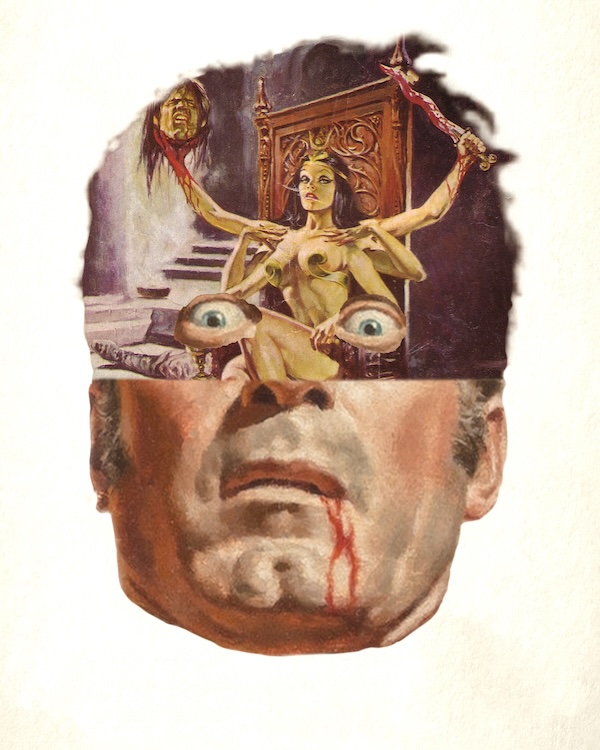

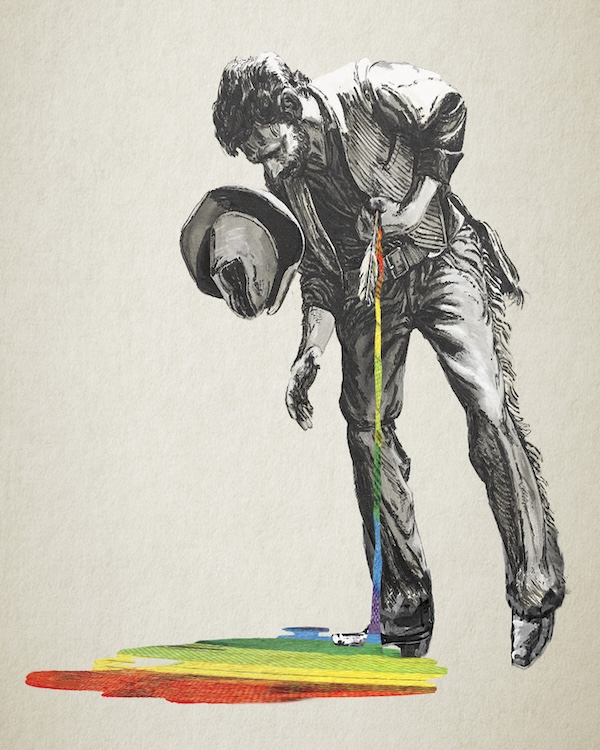

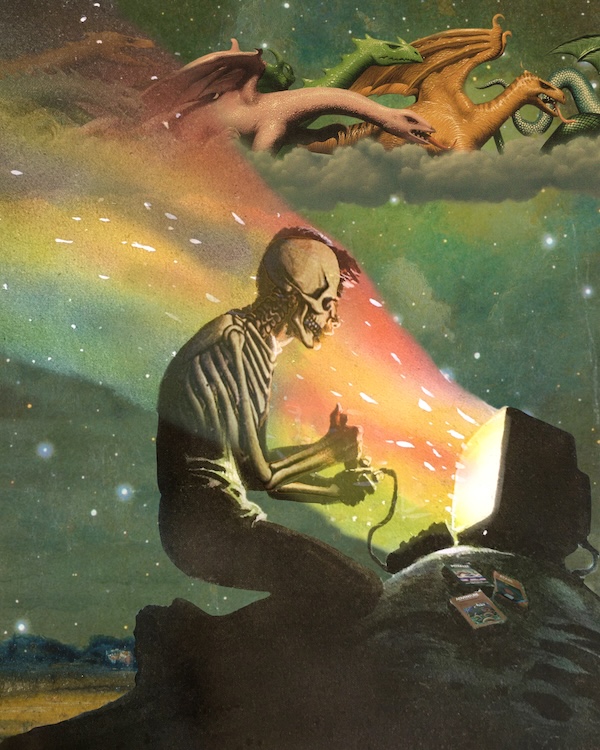

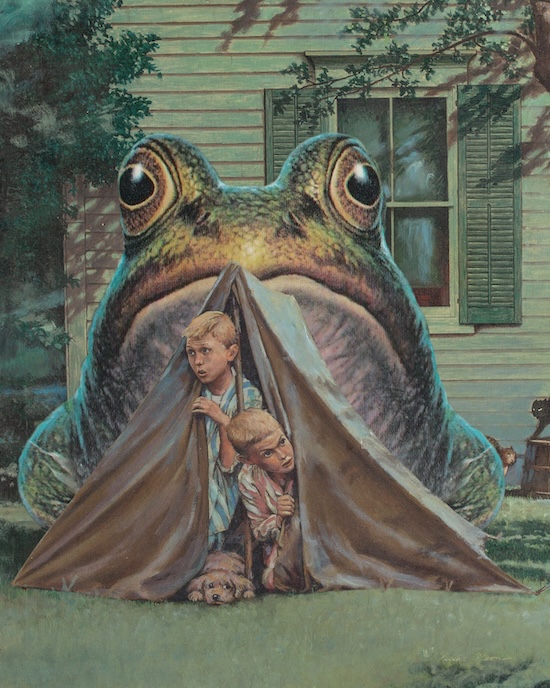

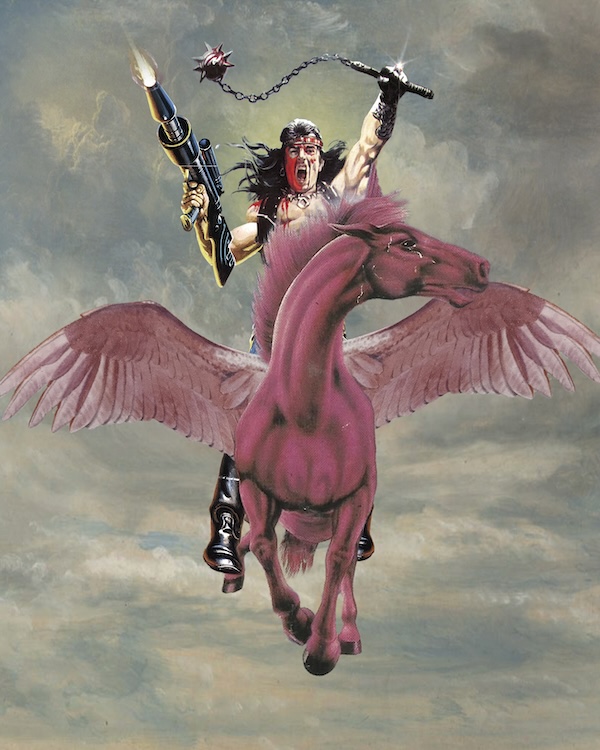

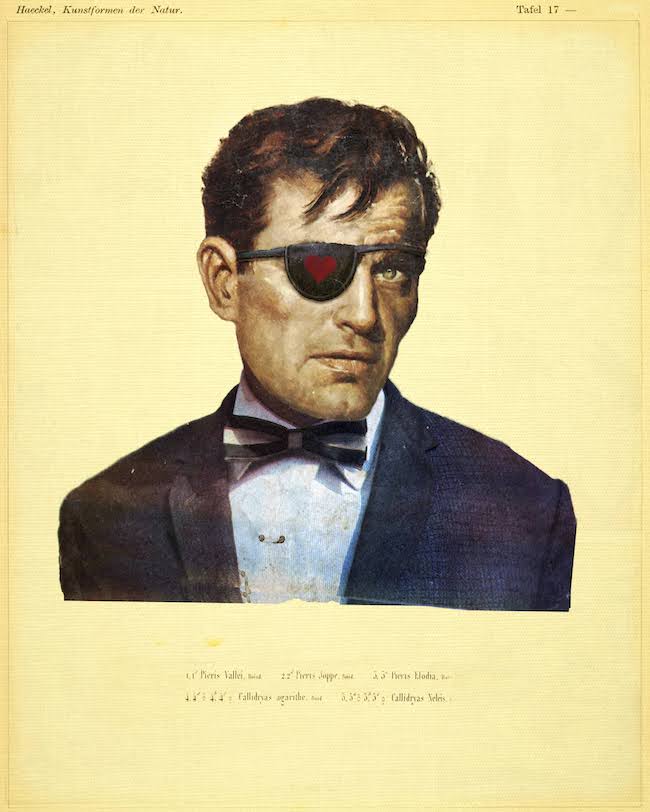

Clockwise from top: Mrs Robinson, Kiss of the Spider Woman, Rainbow Blood and Atari Nights

CC: There are strong elements of sci-fi, folklore and horror in your work, along with references to pulp fiction and illustrations, video games, cartoons and more. What appeals to you about these genres and themes, and what sources do you draw on to create your collages?

MP: We’ve always been interested in genres. Beowulf is one of the oldest and most often translated works of Old English literature, and not only does it have a dragon and sea trolls and a superhuman protagonist, but it has two of the best horror genre monsters of all time: Grendel – and his absolutely terrifying Mum. It’s a superhero story and a horror story at the same time! You can’t get more genre than that! And this text has more than just survived to the present time: it’s been rejuvenated every few decades with fresh translations. Compared to the Old Testament, Indian epic poetry and Greek myths, Beowulf is actually relatively late to the party. We love those older stories too. We are attracted to the fantastic and we always have been. Sci-fi, comic books, video games – all of these are just echoes and iterations of this atavistic love of the fantastical, of the over-the-top narrative tradition that hints at a world or state of being that breaks the laws of everyday existence. These modes of storytelling appeal to me for the same reason they appeal to everyone else to one degree or another – because they take us out of the mundane, and everyone craves that.

CC: Your art seems to have a distinctly retro aesthetic – one of my favourite collages is Hypothetical Movie Poster 1, which references classic characters and tropes from ’60s, ’70s and ’80s horror cinema. Would you describe your work as nostalgic? If so, why (or why not)?

MP: I have fond memories of my childhood, but I don’t think of my work as nostalgic. Nostalgia requires a sentimental yearning for a return to some past period. I don’t want to go back to the ’80s or ’90s, even if I love much of the art and artifacts that come from those time periods. The pulp era and the ’70s are before my time, so I don’t think I even could feel a true nostalgia for those times. I’ve rebuilt much of the comic-book collection that I lost after I moved out of my mum’s house in my teens, back in the early ’90s. And although I’ve enjoyed reacquainting myself with these old issues, I notice that they don’t hit me in such a profound way now as an adult, not like how they hit when I was a kid. This goes for pretty much everything from my childhood. I have fond memories of The A-Team and MacGyver and Magnum PI, but try watching those shows now and you realise you need to be stoned to truly enjoy them without irony. I still love these old comics and TV shows, and I will continue to collect them and watch them, but they won’t allow me to really experience again the formative experience that they provided when I was growing up simply because I’ve grown up. Nostalgia is a mirage; it’s magical because you’ll never be able to put your hands on it ever again.

That said, there are certain aesthetics from the twentieth century that are just absolutely awesome. The pulp art, comic books, movie posters, paperback covers – all of these were disregarded as garbage commercial drivel in their time, but they’ve aged like fine wine. And as a collage artist, I have the very practical consideration of needing as much source material as I can utilise, and that means tapping into the commercial art of every decade of the modern age. My work is retro for this very reason; as a collage artist, I need to reach backward in time to gather up as much source material as I can to make new art.

CC: I always enjoy seeing certain styles or ideas recur in your work – for example, you have several collages that feature a face wearing sunglasses that reflect a different image back to the viewer, and several collages that feature two different faces spliced together as one. What brings you back to these particular aesthetic approaches?

MP: I love the idea of masks, of façades, of people and entities wearing faces to go out into the ‘real’ world and do their business. One of Neil Gaiman’s best Sandman issues is titled ‘Façade’ and Gene Wolfe’s magnum opus, The Book of the New Sun, uses the idea of masks to outstanding effect. Weird fiction is rife with the idea of false faces. One of the grandaddies of cosmic horror, Robert W Chambers, in The King in Yellow, has one of the best ‘fake play’ excerpts that so deftly uses the idea of masks:

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed, it’s time. We all have laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda) No mask? No mask!

Wolfe’s second book in his sprawling Book of the New Sun has a long excerpt of another ‘fake play’ that also uses false identities, and this is modelled on Shakespeare’s comedies, which run on the humour of mistaken identity. HP Lovecraft’s The Whisperer in Darkness and Stephen King’s ‘The Boogeyman’ each use the idea of masks to great effect, as does TS Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock’.

But beyond these genre interpretations of the idea of masks, I think we love the idea of hidden identities because we all relate to it in a very personal way. We all – all of us – have to wear masks. Whether it’s called ‘code switching’ or ‘professionalism’ or if it’s having a blow-out argument with our partner on our way to a dinner party and then putting on our ‘best face’ at the front door – it’s all masks. We all do it. All the time. So the idea of false faces and masks isn’t just titillating in the sense of fodder for horror stories and true crime dramas, but also it’s intensely personal at a day-to-day level of basic social survival.

Image credits: all courtesy of Moon Patrol

Share article

About the author

Moon Patrol

Moon Patrol is a digital collage artist who lives in Northern California. Taking themes from '80s cartoons, Silver Age comic books, Atari video games...