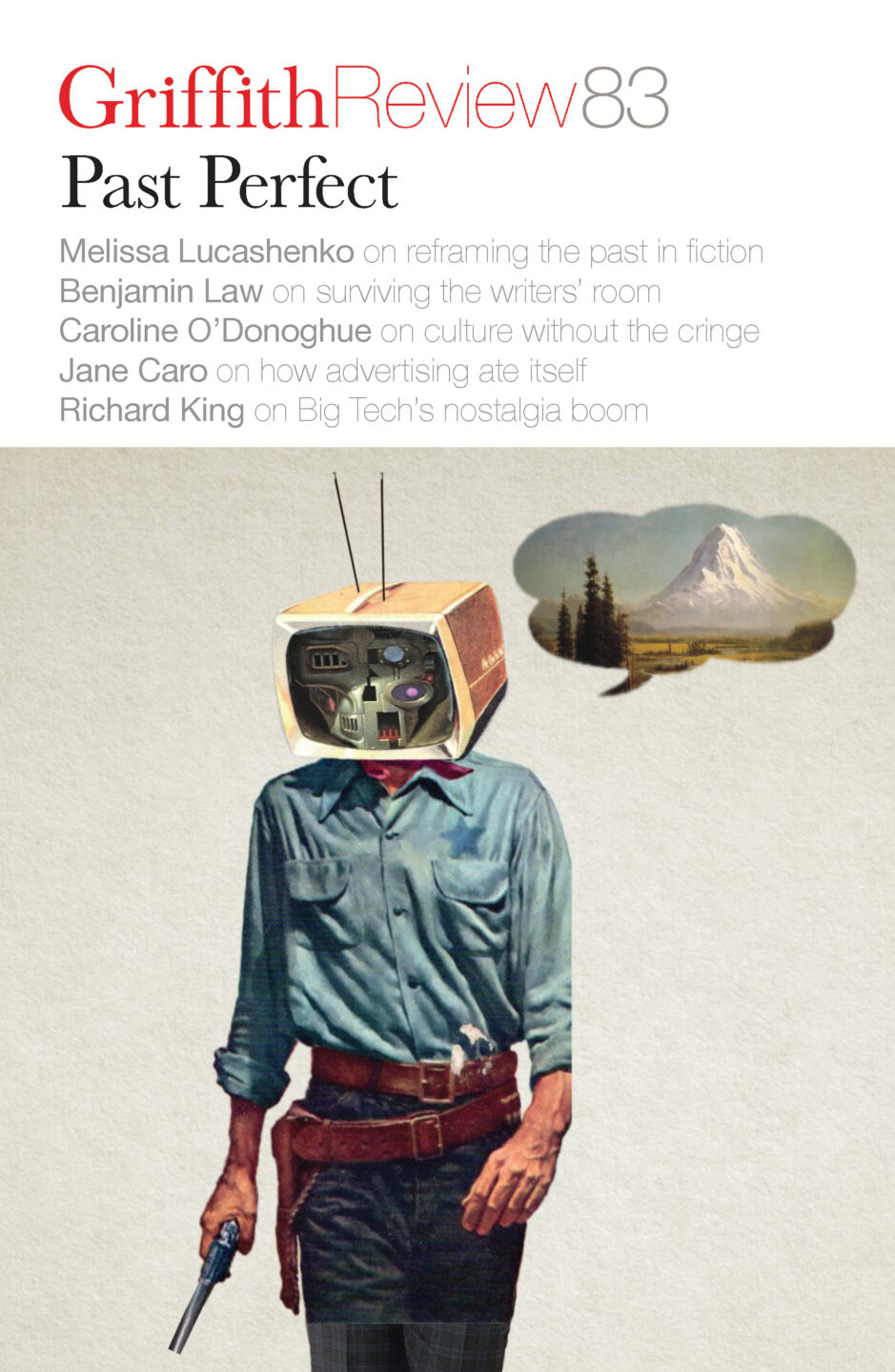

Featured in

- Published 20240206

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-92-4

- Extent: 204pp

- Paperback, ePub, PDF, Kindle compatible

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Michael L Ondaatje

Michael L Ondaatje is Head of the School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, and Professor of History, at Griffith University. He is an...

More from this edition

Glitter and guts

Non-fiction RIGHT NOW, I am obsessed with the past. My debut novel is finished and ready for publication, and I am wrestling with the fear...

Threshold

PoetryWhat is the voice of one who has died if no one listened to what remained unspoken? It no longer matters.

Anticipating enchantment

Non-fictionWhen an editor works on a book, they balance reader expectations with what they interpret the author’s intentions to be and use their experience to make suggestions. This might mean changing some of the language to ensure the work is comprehensible for general readers, or asking for more detail where a setting has been hastily described. An editor will always be anticipating the market, and their extensive reading of contemporary works makes them well-placed not only to understand the social and political conditions of the day but also trends in publishing and marketing.