Featured in

- Published 20221101

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-74-0

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

Already a subscriber? Sign in here

If you are an educator or student wishing to access content for study purposes please contact us at griffithreview@griffith.edu.au

Share article

About the author

Micaela Sahhar

Micaela Sahhar is an Australian-Palestinian writer and educator. Her essays, poetry and commentary have been published in Overland, Cordite, The Age, Southerly, Arena and...

More from this edition

Confected outrage

EssayMany of us can name our favourite childhood lollies. But what if a lolly’s name, or the name of another popular food item, is out of date? What if it’s racist, harmful or wrong? What happens when the name of a lolly doesn’t work anymore?

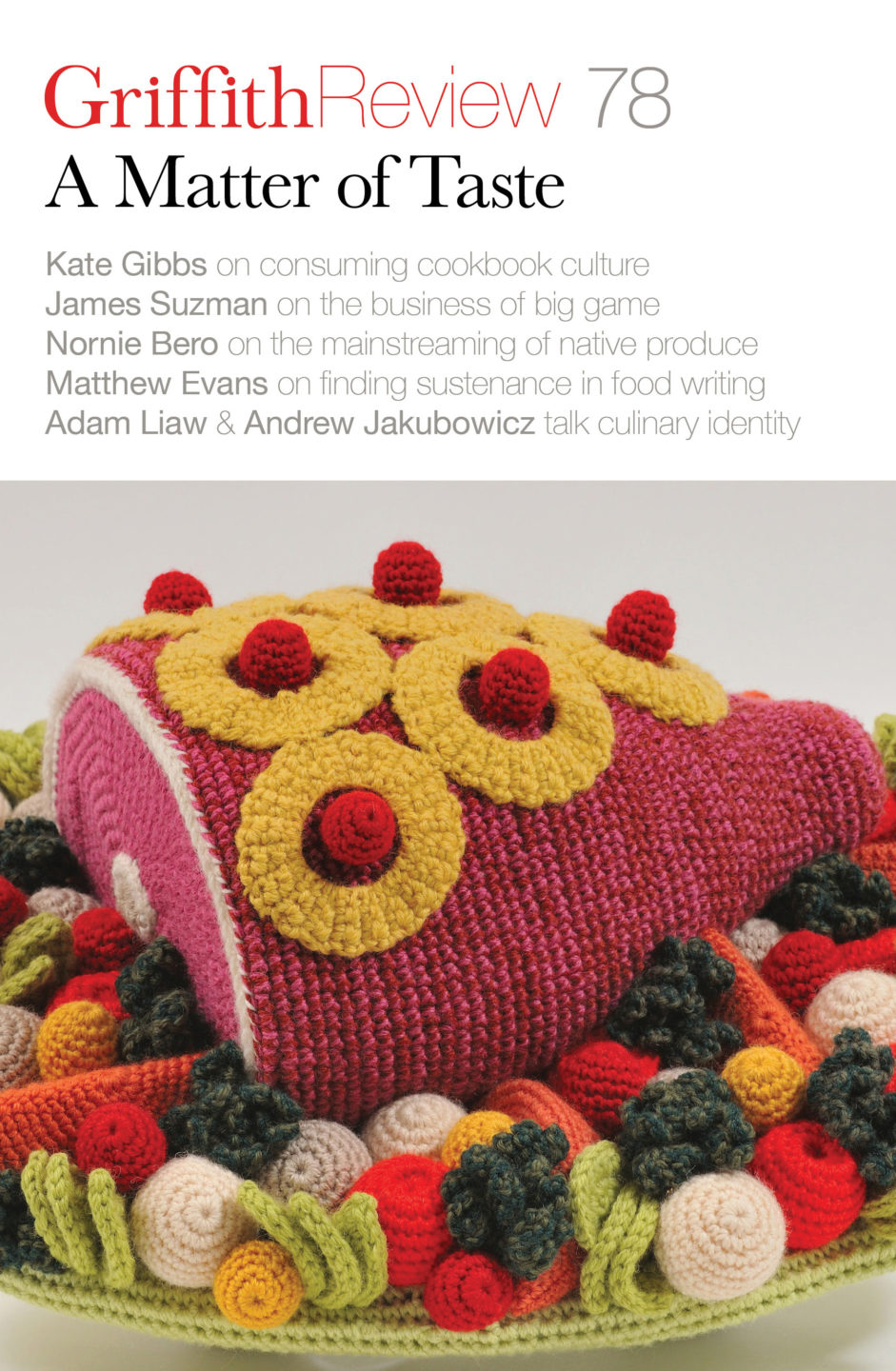

Tastemakers

IntroductionI’m still pleasantly mystified by our obsession with food – our need to talk about it, remember it, photograph it and analyse it, to eat our feelings and compare our lives to buffets and boxes of chocolates.

Dried milk

Memoir THE RUIN OF the new mother is the raspberry. I give Yasmin, her eight-month-old, the bursting prize of the red berry. I know what I am doing....