Featured in

- Published 20160802

- ISBN: 978-1-925355-53-6

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

BOTH NAOMI MCCARTHY and Duncan Free are Olympic gold medal winning athletes. Naomi was vice-captain of the Australian women’s water polo team that won gold at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, and captain at the 2004 Athens Olympics. Duncan first represented Australia in 1991, when he won a silver medal at the Junior World Rowing Championships. He then went onto compete in multiple world championships and four Olympic Games, winning a bronze medal at his first in 1996 in Atlanta, and going on to win gold at the 2008 Beijing Olympics in the men’s pair.

You have both had long careers in elite sport. What have been some of the highlights and low points?

NAOMI MCCARTHY: Ever since I can remember, I have wanted to compete at the Olympics Games, so a highlight for me was definitely the inclusion of my sport by the International Olympic Committee. Men’s water polo has been in the Olympics since 1900, but women’s water polo was only introduced in 2000.

Following that, winning the first-ever gold medal for women’s water polo was very satisfying. It was the culmination of six years of work for us as a team, and to achieve that result in front of a home crowd at the Sydney Olympics was amazing. I will never forget standing on the dais in front of seventeen thousand people, singing the national anthem – and then the party that followed for the next couple of weeks.

My lowest point was probably then losing the bronze-medal match at the 2004 Athens Olympics. We had worked hard to improve, particularly in the twelve months leading up. We should have been in the gold-medal match, but we didn’t perform well during the tournament. Those Olympics were still a great experience, but they really brought home the lows of competition.

DUNCAN FREE: Sport has brought so much into my life. It’s not just about the good times, the travel and the success, but also a great deal about what you can learn as an individual and as part of a team.

My senior representative rowing career spanned about twenty years, and included four Olympics Games. Looking back on how I developed as a person and as an athlete is quite interesting, for me at least. Witnessing in myself that transformation from a young kid who didn’t really have great confidence in his sporting ability to a senior athlete who knew no limits was definitely a highlight. And rowing with Australia’s most successful Olympic rower, Drew Ginn, to win an Olympic gold medal in 2008 is a moment that will be at the forefront of my memories forever.

Another highlight was rowing with my brother, Marcus, and winning a bronze medal at a world championships. Topping this experience off was the fact that our father coached us, which is extremely unique.

A low point in my career was undoubtedly the 2004 Olympics in Athens, where I was a part of the quad scull. We had won the major lead-up race six weeks earlier and were in great form until the Olympics came. We lost composure – physically and most certainly mentally – due to a number of factors that we could have collectively handled better. We ended up missing out on the final six and won the ‘B final’ – placing seventh overall. However, the lessons I learnt from that experience were a major contributor to winning the gold medal in Beijing four years later.

Are there things you have had to sacrifice, and regret sacrificing?

NAOMI: The main thing that I sacrificed over the years is time with my family and friends, and a social life. I spent many months away from family every year for over ten years, and while much of it was great experience, there were plenty of overseas destinations that were far from fun or even comfortable. Even small things like booking concert tickets or weekends away were not possible as I never knew exactly where I would be or what my commitments were months in advance. It was, of course, all worthwhile – but there were times when it was hard missing out on weddings and birthdays.

DUNCAN: Absolutely no regrets! It’s not a sacrifice; it’s a choice. For me, the choice to continue to row for as long as I did was a joint decision with my wife, Belinda. Without that support, it would not have worked and my rowing career would have become difficult to the point that I would have questioned whether to continue. Support is critical.

Sure, I often had to miss out on a few things in my life that clashed with training and competition, both domestic and international. However, sport taught me so much about life and about myself that all the choices I made along the way and things that I may have missed out on were worth it.

How have you seen high-level sport and the demands on athletes change?

NAOMI: During my time as an elite athlete I have seen a big change in the amount of training and competition required to succeed. Sport has become more and more professional over the years, and it continues to do so. The preparation for something like an Olympic Games is huge: I lived in a residential camp away from home for all of 2000 and most of 2004, and spent up to six months travelling and competing in the three years prior to each Olympic year. The demands of training, travel and competition are now constant and it can make it very hard for athletes to find a balance outside of sport.

More recently, I have also seen a big shift towards younger ‘elite’ athletes specialising in their sport much earlier and not being able to play many other sports. When I was a developing athlete there was time to play a variety of sports over the different seasons, something that helped develop a variety of skills and also kept me interested in my sport. This doesn’t seem to be the case these days, and I think it has some influence on the high dropout rate of athletes in their late teens.

DUNCAN: My first senior team saw me as a ‘poor’ university student: I received very little athlete funding, and delivered pizzas of an evening. Luckily, I was living at home with my parents. Then I transitioned to a career in banking, got married, acquired a mortgage and had children. Like most rowers, I still had to work while squeezing in training. During the 2000’s, the demands of being an athlete seemed to increase; fortunately, so did DAS (direct athlete support) funding, which made life a little easier – as did the fact that my wife was also working.

Leading into 2008 and 2012 Olympics, time demands on athletes grew to the point that the sport almost owned them. Athlete training grants increased (depending on international results), as did the time required for training and domestic and international travel. Some sports now very nearly require athletes to relocate to a particular training centre in a particular city to have any hope for national team selection. (Of course, there are always considerations for the exceptional athlete who may have family commitments that prevent this.)

So while the financial burden on high-level athletes has eased somewhat over the years, the time demand has only increased. This has been compounded by advancements in technology – sports science, sports medicine, nutrition, psychology and biomechanics have resulted in changes to testing, training and treatment that all require time.

Does Australia place too much pressure on athletes to perform, particularly those athletes with results already on the board?

NAOMI: There’s an enormous amount of pressure placed on athletes to get really good results, and an expectation that Australia will continually punch above its weight internationally. We saw this in London 2012, where many athletes were devastated with performances and some commentators were unhappy with the overall results from Australia. I believe we’ll see a better outcome in Rio 2016, but the pressure of expectation on athletes is huge and often unrealistic.

DUNCAN: As funding has increased, I believe it is accompanied by a fair amount of pressure on athletes to perform. This pressure may come from the government funding agency or the sports body, or both. This was not necessarily the case for me. The main pressure that I felt in the lead up to the 2008 Olympics was from myself. We had a successful couple of years leading into that Olympics so I knew we were capable of winning gold – hence the self expectation to succeed, perhaps tinged with a fear of not being able to reproduce that performance. We didn’t get caught up on the media stories or public expectation, though – we stayed in our bubble and focused on the job at hand. Many athletes can get distracted by these things, which sometimes become worse in their heads and can hinder performance.

What separates a very good athlete from a high-performance or elite athlete, particularly on the mental side of things?

NAOMI: At the elite open level everyone is very talented, but the athletes who succeed internationally are constantly the strongest trainers, willing to put in extra work over the course of years, and are the ones who look after themselves the best. I’ve seen many athletes who have the ability to reach any level but aren’t willing to do the extra work on their recovery, sports psychology and rehabilitation, in addition to training, to absolutely perfect their game or their current skills. A really good example of this was from our 2000 Olympics water polo team. We won the gold medal with a goal that was shot from a long way out, with less than two seconds remaining in the game. The girl who shot it consistently practiced that very shot after training sessions for years.

DUNCAN: For me, it’s the realisation that we are far more capable than what we think, both physically and mentally. It’s what turns places in Olympic finals into Olympic gold medals – the ability to comprehend this fact combined with the confidence to deliver on it in everyday training and during competition.

Along with this realisation, athletes need to ensure they have no regrets and that everything has been done in the most professional way possible. There are so many other elements besides simply training hard and receiving the physiological benefits – and one of the most important is having that perfect relationship with your coach and teammates.

What role does the university play in nurturing high-performance athletes?

NAOMI: Universities in Australia plays a different role to universities in other countries. At Griffith University, we provide a supportive environment, assisting athletes to compete at the highest level and still progress through their studies. It can be hard to find a balance with sport and study, but it’s essential for our athletes now and in retirement. We are a part of their general development as an athlete and a person, but not really involved in their high-performance sport directly. Overseas, particularly in places like America, this is different – universities also look after the high-performance development of their athletes. There’s a lot of debate within elite sport in Australia as to whether this is a model that we should, or even can, move to in the future.

DUNCAN: Universities in Australia plays two main roles within sport. The first is bringing balance bring to an athlete’s life in the form of study. At Griffith, we create a very flexible environment that facilitates stress-free study for athletes. This helps ease the burden of their daily training schedules, and also prepares them for life after sport.

The second role comes with increasing partnerships with Australian sporting bodies, and the high-performance services universities can deliver. This may include sports science and medicine services, research, sports management, internships and facilities.

Is it important that athletes have something outside their sport to focus on? How has it assisted you during your career and into retirement?

NAOMI: I believe it is vital for athletes to have something else to focus on rather than just their sport, whether it is study or a career. I did this myself as an athlete and found it gave me some perspective when I had issues with my sport, whether they were poor form or injury. Having something meaningful to do outside of my sport made me a better and a more focused athlete. After finishing my degree, I worked in environmental science and was able to balance part-time employment with high-performance sport. It helped me to develop effective time-management skills, and allowed me to get a foot in the corporate door at the same time as competing. My work and sport gave me a vast network of contacts and opportunities, and led me to a company that both sponsored and employed me for four years. Both my degree and experience working helped me to transition when I retired too – a difficult time for all athletes. I was able to return from my last Olympics and go straight back into a great job, and pursue some opportunities that would not have been possible without my sporting background.

DUNCAN: I strongly believe that having other things in my life to focus on – study, friends, family – while training and competing significantly influenced three fundamental aspects of my sporting career: performance, longevity and retirement. Performance and results can be affected directly by a balanced life – it motivates you and keeps your mind fresh, as opposed to sitting around all day, living and breathing sport but not becoming excited or ‘switched on’ for the session ahead. That’s not to suggest I wasn’t constantly thinking about my sport, constantly challenging myself and others and continually looking for improvement, but this was in combination with mental stimulation in areas that weren’t related. Further to this, having ‘stuff’ going on in your life takes your mind off sport and gives you an outlet – a must in my book for any athlete who wants to sustain their passion and compete for longer.

Finally, it’s much easier to transition into retirement if an athlete has a balanced life. There are two main areas of rationale behind this. First, a balanced life with work and/or study prepares you for a career after sport; second, if an individual is an athlete 100 per cent of the time, when it comes to retiring they are effectively changing their entire life. This can cause identity issues – retiring athletes commonly find themselves asking: ‘Who am I and where do I fit in into society?’ Because I was either studying or working throughout my entire career, come retirement I only had to adjust to perhaps a 50 per cent life change. For me, this was an easy and comfortable process. This isn’t to say I don’t miss rowing and being an elite athlete – the training, competing and travelling – as at times I do. Though I certainly don’t miss the early mornings!

What do elite athletes offer an employer in the work environment after they have retired?

NAOMI: Athletes are, by nature, focused, hardworking and goal-orientated people. They tend to apply these attributes to everything they do and most have high expectations of themselves, whether it is competing as an elite athlete or in the workplace. This drive is something that employers see as a huge benefit. Many employers also like that athletes have often competed as part of a team, so they know they are getting someone who will likely work well in team environments.

Athletes who have completed higher education also demonstrate that they have been able to simultaneously succeed at university and a sporting career, which shows great time management skills, dedication and application. In many cases, their sporting background is what sets the athlete apart from the other hundreds of applicants.

DUNCAN: Elite athletes are generally assets to any organisation. They are committed, highly motivated, great team players and have time management skills. Other skills may include leadership, strategic thinking and decision-making – certainly transferable to any work place.

The combination of these skills with university studies have place athletes in major roles both in Australia and internationally, including in politics, as CEO’s for multinational organisations, and of course in key executive roles within the sporting industry.

What are you most looking forward to this year at the Rio Olympics?

NAOMI: I love watching all Olympic sports, but I particularly enjoy watching sports that don’t usually get much media attention such as water polo, hockey and women’s basketball. A number of athletes from Griffith University are competing, so watching them will make it extra special.

Water polo is of course my favourite, and I’m really looking forward to seeing how the women’s team performs – they are favoured to win a medal, and I think they’re capable of winning gold. My two children are at an age where they enjoy watching sport now too, so to share the Olympics with them will be fantastic.

DUNCAN: Watching it from my couch. I have not seen an Olympics from home since 1992 and am looking forward to it in the comforts of my own home, without the pressure to compete!

Growing up on the Gold Coast gave me a love of all water sports including triathlon, kayaking, swimming. And I’ll always have a passion and close interest in rowing, but I’ll also watch anything else I can get my eyes on, especially when Australians are competing.

I know several athletes who will be competing this year, including our Griffith University student athletes. It’s been exciting to watch their journey over the past couple of years and to be a part of that journey and their development, both on and off the field.

Share article

About the author

Duncan Free

Duncan Free first represented Australia in 1991, when he won a silver medal at the Junior World Rowing Championships. He then went onto compete...

More from this edition

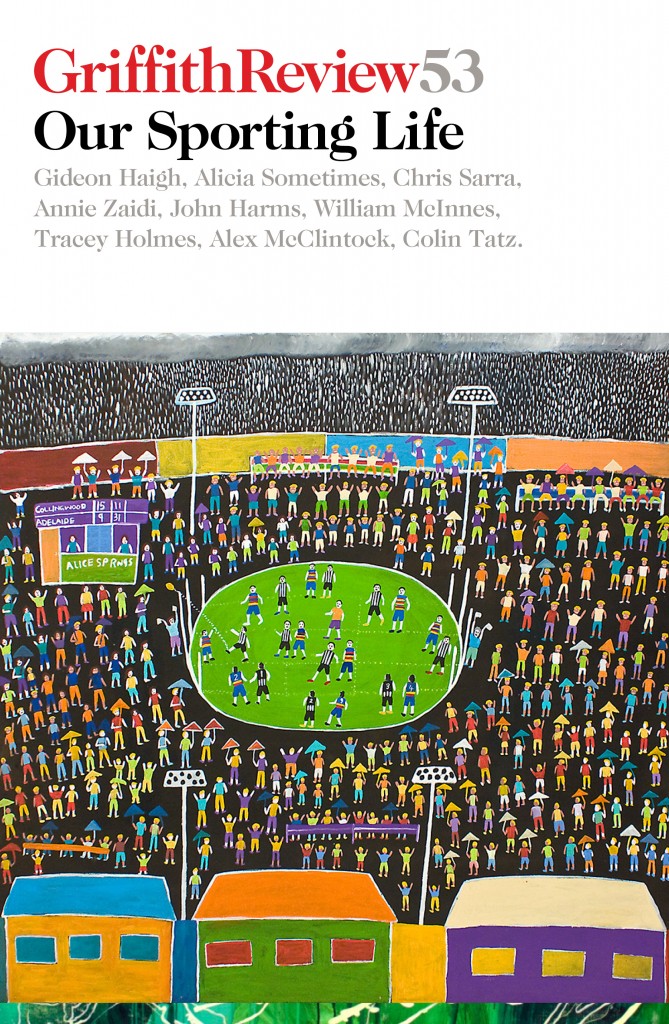

Transient triumphalism

EssayMUCH OF MY life is spent writing about race politics, suicide and genocide. For relief, I write about sport – but that doesn’t always work....

Personal score

MemoirSeasonBY QUEERTIME SHE grew restless and could not see what was in front of her. She felt rootless and lived alone; her friends were...

The stands

PoetryWaverley. You were my Saturday crèche when I was too young to see over the fence on the wing. My Tuesday night series teen...