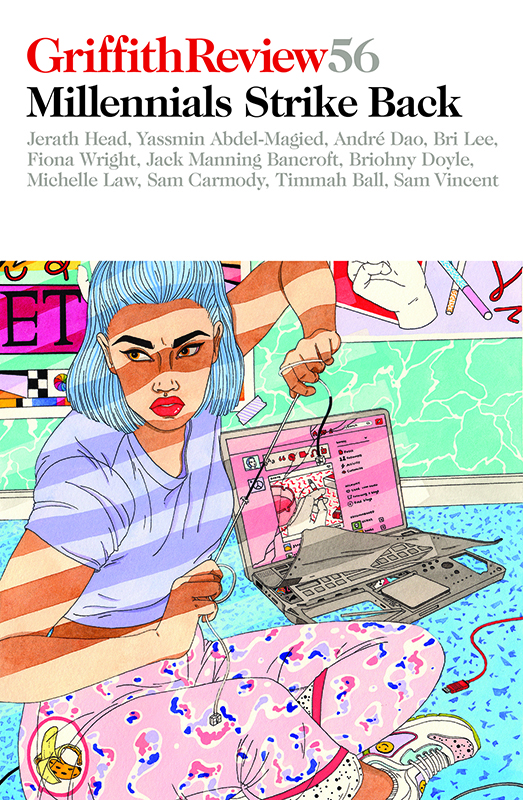

Featured in

- Published 20170502

- ISBN: 9781925498356

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

FOR AUSTRALIANS WITH disability, and their families and friends, it feels as though opportunity has never come knocking quite as loudly as it has in recent years. In 2013, the Australian Government approved the implementation of a new National Disability Insurance Scheme, and following three years of a trial phase the scheme’s official roll out began in July 2016. After decades of a welfare-based disability support system that seemed to encourage dependency rather than promote independence, the NDIS has the potential to transform the lives of almost half a million people.

Around 2 per cent of Australians have a severe physical or intellectual disability, but because the vast majority of the other 98 per cent tend to assume it’s something that could never personally affect them, disability policy issues have historically received very little political, social or media attention in Australia. Year after year, Australia has languished at the bottom of all OECD, UN and other international surveys that compare outcomes for citizens with severe disability in Western nations, including such basic quality-of-life measures as unemployment rates, educational participation and poverty levels. The UK, Canada, the US and New Zealand have all implemented far-reaching legislative and budgetary reforms, in many instances decades ago, to fund all necessary services and supports for citizens with severe disabilities.

The Whitlam government was planning to implement such an overhaul of Australia’s support system in 1975, but was dismissed before the necessary legislation could be passed. Since then, other countries have also introduced reforms to ensure that individuals requiring disability support can enjoy personal choice and control over the public funding allocated to them, enabling them to choose and manage their own home-care and support workers, for instance, or select their own therapy providers.

By implementing similar reforms, the NDIS aims to establish a more effective and nuanced disability support landscape than the system that preceded it. But while it passed through parliament with bipartisan support, the NDIS is at risk from the Australian disability sector’s more divided response.

Many service provider organisations are grappling with the impact of the scheme on their services, staff and clients, straddling the divide between what has been and what could be. To smooth the transition and build an NDIS that allows organisations to both do the work they deem necessary and provide people with the best-possible support, we will need a sector-wide, all-hands-on-deck approach to its implementation. If this doesn’t happen, and if those with years of experience in this sector resist the need for new thinking and new solutions, the NDIS will likely fail. We must work together to build a new Australian disability landscape that takes inspiration from all generations, organisations and health professions.

I GREW UP alongside a younger brother, Shane, who had a severe physical disability as a result of brain damage at birth. I came to understand – not only because of Shane, but also from engaging with and working in the sector over the years – that severe disability is something that can actually happen to anyone, at any time. The list of conditions that can suddenly bring about serious disability, whether from birth or later on, is a lengthy one: multiple sclerosis, autism, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, brain injury, spinal cord injury, chromosomal or genetic abnormality, near-drowning, muscular dystrophy, blindness, cystic fibrosis – the list goes on. A fit, healthy, athletic teenager can go for a surf on a summer’s day, dive in, hit a sandbank and in an instant be left a ventilated quadriplegic. As Graeme Innes, a former disability discrimination commissioner, recently wrote for The Guardian, ‘We are the Australian disadvantaged minority that anyone can join.’

The last thing my career-focused parents ever anticipated was having to care around the clock for an infant with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy. But they did. And, as a family, in the years following Shane’s birth we came to realise that the disability care and support system in Australia – on which all but the very wealthiest families are forced to rely for expensive but vital day-to-day assistance – left a great deal to be desired.

In the mid 1990s, when Shane was five years old, my fed-up parents moved my brother, my sister and me to the UK so Shane could attend a world-class school that specialises in helping children with his form of disability. Nothing like it existed in Australia. When we eventually returned in 2008, we found the system to be as fragmented, disorganised and inefficient as when we’d left. However, one thing was different: the appetite for change was gathering momentum.

From around 2007, a few visionary reformers across the country began working on transforming Australia’s disability support system, proposing a radical new approach that would see the old, fragmented and underfunded state- and territory-based system replaced with one uniform, gold-standard national system. These reformers dubbed their concept the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Given the fraught nature of Commonwealth–state relations in this country, only the truest of believers gave this seemingly pie-in-the-sky idea the slightest chance of coming to fruition. But then something rare in Australia happened, an event that Julianne Schultz describes in Griffith Review 52: Imagining the Future as ‘a bold experiment in collective imagining’: the Australia 2020 Summit, convened in April 2008 as one of the first acts of the Rudd government, brought a thousand people together in Canberra ‘to imagine what the nation could be like in a dozen years, and the steps that needed to be taken to achieve the change’.

After two days of numerous ideas being presented and debated, all jostling for attention, delegates voted the NDIS one of the brightest to have emerged; Prime Minister Kevin Rudd told various delegates that he considered it the best and most promising of all. Soon after, Rudd’s then junior parliamentary secretary for disabilities, Bill Shorten, established a panel of business leaders to investigate the idea, which led in turn to a landmark inquiry and report by the Productivity Commission that strongly recommended the scheme’s introduction. Legislation establishing the scheme passed through federal parliament in 2013 with, almost miraculously, unanimous support from all members of parliament and senators.

The NDIS is a radically innovative reform and a wonderful example of the power of collective imagining, particularly within governments – but it’s only the beginning. If the scheme is to be a success, then as disability reform activists, consumers and participants all involved in its implementation, we in turn need to respond with innovation, to think creatively and to use this new system to its full potential.

Previously, large disability organisations and service providers received block grants from governments. Now, people eligible for the scheme are entitled to individual funding packages, to spend as they choose. Funding is allocated following a needs-based assessment that takes into account each individual’s education, employment and community-participation goals. It asks what kind of independence and personal growth a person would like to achieve and then seeks to support those goals. Australians with disability have been given control and choice over their own support services for the first time in the nation’s history and, with this, a market of newly empowered consumers has been created.

As revolutionary as this change is, some also find it daunting. Effectively transforming recipients into consumers turns the market on its head and presents a considerable challenge for many traditional service providers. To adapt to the NDIS, organisations are being forced to reconsider their purpose, the services they offer and their operating models. And with good reason. For too long, people with disability have been subjected to very poor outcomes in the areas of social inclusion, economic participation and political representation in Australia. One in five Australians identify as having a disability and for those with severe to profound disability, the unemployment rate is almost three times the national average. But it isn’t this high because people with disabilities don’t want to work, and social isolation is rarely a choice. To fully participate in community life, many people with disability have no option but to rely on a taxpayer-funded support system.

OVER THE YEARS, both here and in the UK, having home-care and support workers around the house was part of our family routine. In the UK we were able to interview and choose these workers for ourselves, but once we returned to Australia we found a system that still gave us no choice or control. Each morning, someone would knock on the door at around 7 am, sent by an agency that was in charge of scheduling and sending workers to care for Shane; whether or not Shane happened to like, feel comfortable with and be able to communicate with them was a matter of chance. This was meant to be a person who could provide him with intimate, one-on-one support with things like showering, dressing, firing up the computer and enjoying time with his friends. I still remember my brother’s unease at having to spend the day with a worker he didn’t like.

This was the way the Australian disability sector worked for a long time – and is still working in many regions of the country that the gradual rollout of the NDIS, due to be completed by 2020, has not yet reached. This system is also financially wasteful and inefficient, with large overheads for staff and infrastructure pushing up the hourly cost of support work, and middleman agencies often charging double what is eventually paid to the support worker. People with disability and their workers have to communicate through these agencies, and are often barred from directly contacting each other outside their shifts together.

In 2013, when NDIS legislation passed through federal parliament, social networking on Facebook was already nine years old. EBay, one of the first peer-to-peer platforms, had turned eighteen, and Uber and Airbnb, the best-known members of the so-called ‘gig economy’, had been around for four and five years respectively. Online platforms and apps were making the world a more connected one, bringing people and communities together on the basis of their commonalities and shared interests. Technology was being used to drive down costs and provide better access to goods and services for people in rural and remote regions. The internet was allowing businesses to scale faster, build new service models and use data to support their customers more effectively and efficiently.

It made no sense to my sister and me that while we were watching our worlds open up with opportunities to study and work, our brother’s was closing down. Knowing what effective support looked like, we were aware that his independence began with being able to find support workers he liked and had chosen for himself. In 2013, we started thinking about a new way that people with disability and their families might be able to do this, one that used online technology to connect people directly.

Four years down the track and our online platform, Hireup, is now used by thousands of Australians with disability and their families to find, hire and manage their own support workers. Hireup connects people with disability and support workers directly. No third parties, middle men or bureaucracy. We started Hireup to empower people with disability, but by doing so we knew we’d also be empowering a workforce of support workers to take ownership of their work. Hireup workers are able to choose who they support and when they work.

Online platforms like ours are changing the nature of the workforce, and not just in the health and community-care industries. Multi-sided, peer-to-peer platforms like Uber, Deliveroo and Airtasker are giving people the opportunity to work when, where and how they want. Work is contracted on a once-off basis and people can arrange their work around their own schedule.

For the most part, workers of the gig economy are classified as independent contractors, as opposed to part-time or casual employees. In October 2016, however, a UK employment court ruled that Uber drivers are not self-employed and should be classified as employees rather than independent contractors. If this happens, Uber drivers in the UK could be entitled to benefits like the national living wage, holiday pay and pensions. While Uber is appealing the decision, this is a landmark ruling. It sheds light on the murky waters of employment law and the line between independent contractors and casual or part-time employees.

Employment models in the gig economy should be determined on a case-by-case basis. What is right for the ride-hailing industry might not be right for the design industry. And what is right for delivery and logistics companies won’t be right for care providers. For the Hireup community, engaging our workers as casual employees was the right approach. Having had a lot of experience as a support worker and carer myself, I was acutely aware of how much families relied on them and how important it was they be properly valued. As employees, our workers are guaranteed industry-leading wages, they don’t have to negotiate their own fees with the people they support, and they receive penalty rates and casual loadings. We also follow the relevant industry award, provide comprehensive insurance cover to protect our employees, and make superannuation contributions on their behalf.

But a model like ours could not have been imagined without first introducing a reform as innovative, radical and disruptive as the NDIS. As the revered British social entrepreneur Liam Black puts it, ‘Ask yourself this: without political backing where will your idea get? What has had the biggest impact on wellbeing in this country over the last ten years? Eden Project? Big Issue? Jamie Oliver? Divine Chocolate? Or the government’s decision to ban smoking in all public places?’ There is no doubt that without bi-partisan political support, opportunity would not have come knocking.

Only five or so years ago, the vast majority of Australians had never heard of the NDIS, and of those who had, almost all would have described it as a pipedream. The concept of any government agreeing to spend $22 billion on one uniform, national system of disability support funding seemed extraordinary. But that’s what happened. This is a landmark moment for both disability support and the future of innovative policy in Australia. It is an opportunity to prove that new thinking can harness the best of what has been and infuse it with a sense of what could be. To build better, more effective and cost-efficient services that foster healthy, more self-determined communities.

Share article

About the author

Jordan O’Reilly

Jordan O’Reilly is the co-founder and CEO of Hireup, an online platform that enables Australians with disability and their families to find, hire and...

More from this edition

A gonzo music memoir

EssaySO YOU GET an urge. Something bristling within you that can only get out through something else. Maybe it was because you didn’t fit...

Your sons, your daughters

EssayWEARY WORKING WARRIORS of Australia, we need to talk about what your heroic long hours, your selfless overtime, and your lack of self-care is...

Still talkin’ up to the white woman

MemoirTHE NAKED WOMAN is only visible when my manager’s door is open – when closed it is unclear what the painting depicts. From my desk...