Welcome to GR Online, a series of short-form articles that take aim at the moving target of contemporary culture as it’s whisked along the guide rails of innovations in digital media, globalisation and late-stage capitalism.

All creatures great and small

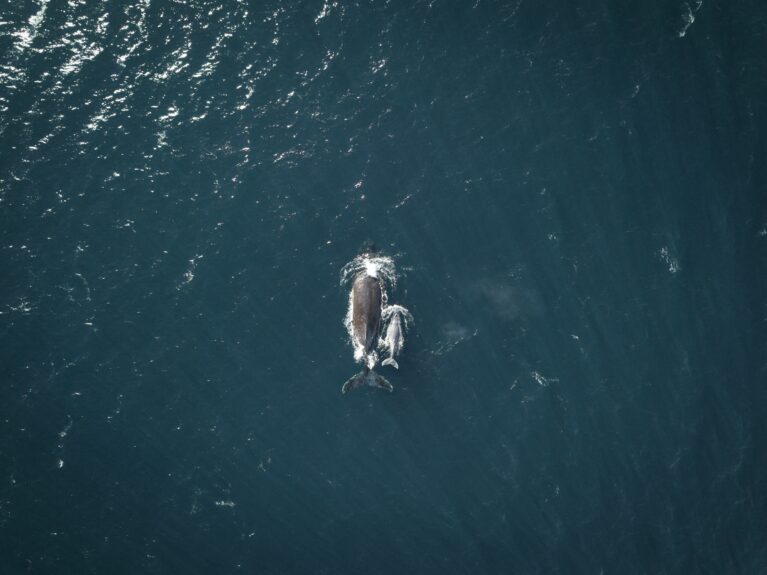

There are strong links between public opinion and the direction of scientific research, conservation funding and legislated policies, meaning that biases in the way we communicate about species within popular culture have tangible effects: the most favoured species receive the bulk of our research efforts, conservation initiatives, academic publications, ecotourism visitors and threatened-species listings. At a time when global biodiversity is rapidly declining, then, these trends raise concerns for at-risk species that don’t enjoy a prominent or positive public profile.

A storyteller’s journey

You produce content and people say, ‘Oh, you need to tell people about this, or the Stolen Generations, or the stolen wages.’ We’ve still got to repeat that story, which should have been told and embraced by Australia, as ugly as it is, so we can move on. So, I started telling my own stories for me and my people to remind us what a great culture we have. As human beings, we’re pretty deadly.

Unhappy pairings

Arts, creative arts and humanities courses teach critical thinking, civic discourse, emotional literacy and storytelling. Most students are grappling with rent, menial work and advanced study. In a world that seeks to destroy their attention span, arts courses teach young people to read, think critically and provide historical context and sensitivity to complex issues.

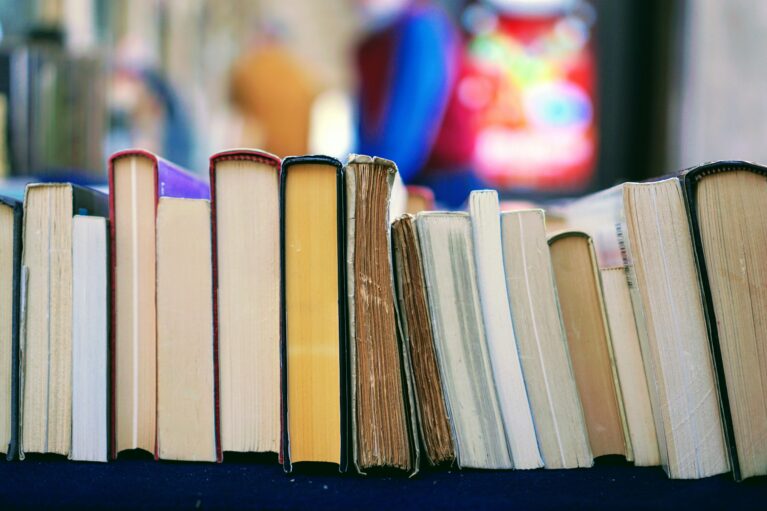

The many tragedies of Animorphs

Animorphs has been out of print for twenty years, yet its cult following remains fierce. If your knowledge of Animorphs is limited to the cover art, I’m sure that’s a bemusing claim to read. However, if you did read the books, then the unlikely endurance of Animorphs is really anything but.

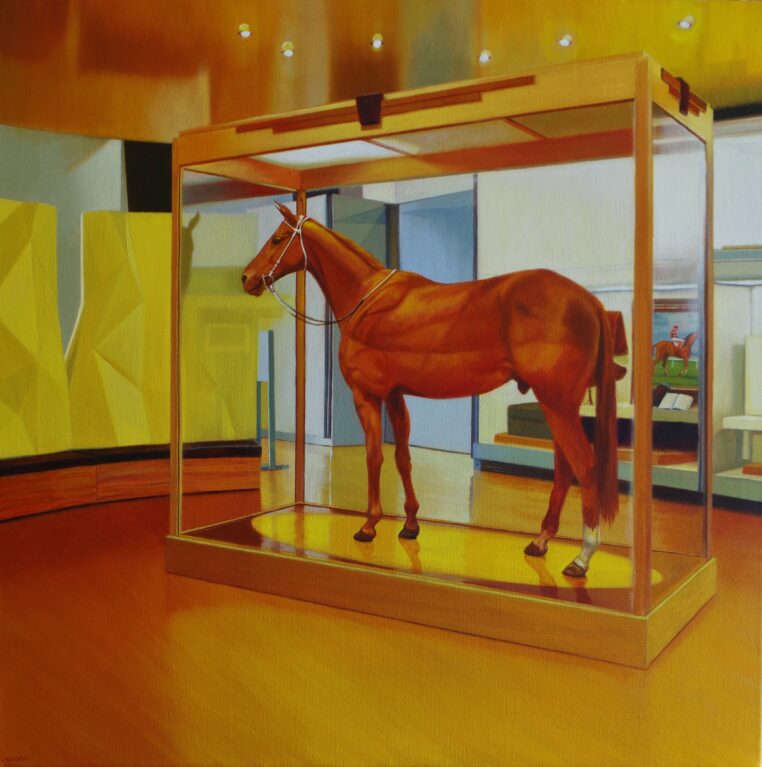

Subject, object

The vivid hues and spiky leaves of Jason Moad’s Temple of Venus – the arresting artwork featured on the cover of Griffith Review 89: Here Be Monsters – raises a tantalisingly sinister proposition. The subject of the painting is clear – a Venus flytrap, realistically rendered – but there’s a somewhat otherworldly quality to this plant, a sense that it might be biding its time, waiting to strike while we, the viewers, are distracted by its beauty. For Melbourne-based realist painter Jason Moad, this slippage between subject and object, reality and imagination, is part of the point.

Cherry chapstick

Before we railed on Katy Perry for her love of astrology, we piled on her lipstick lesbianism. Pseudo-sapphics copped a lot of shit – maybe we should shovel some of it onto the pseudo-socialists. Evidently, there were plenty of liberal cosplayers who are now back in their weekday clothes and killing it at the (government) office.

Nature through a different lens

Over the course of his remarkable career, Attenborough has taken us not merely to places most people are unlikely to visit but to places that are impossible to visit – into birds’ nests, burrows, termite mounds and the deepest recesses of the oceans. We’re shown things we will never encounter ‘in the flesh’ and that are simply not available to our senses as we navigate our daily lives.

A tough sell

While mine is a unique pathway to publication, the length of time it’s taken, the number of rewrites I’ve completed, and the thinly (and sometimes not-so-thinly) veiled racism that I’ve experienced are not unique when it comes to the journeys of authors who are First Nations and People of Colour (FNPOC).

The drifting Miles Franklin Literary Award

Collectively, these works reveal to us, if we care to listen, an Australianness that is weird, wonderful, awful, impossible, contested and messy – less chicken parmi, more all-you-can-eat smorgasbord, including the odd cut of meat that’s turned.

Who’s next?

Tackling societal issues and politics in horror is, of course, nothing earth-shattering. Horror has long been grounded in political allegory – always passionate, often cheap and gory – to push against cultural boundaries and confront the ugliest sides of humanity: misogyny, homophobia, xenophobia, classism.

Trans as monster

A near future in the West in which access to gender-affirming surgery and cross-sex hormones is outlawed is no longer unimaginable. Those of us who have updated our sex markers on our passports have begun to wonder if they will be soon declared invalid with the stroke of a pen. It’s already happening in the US and the UK, once the global torch bearers of queer liberation. Why couldn’t it happen here too?

Double vision

My memories of growing up in New Zealand and Australia are a technicolour whirl of cartoons, comic books, science fiction and arcade video games – I guess I’m instinctively drawn to imagery of that era. I love using readymade imagery as a starting point for my artwork. Sixties Pop Art taught me the joys of subverting the mundane and incorporating everyday imagery not necessarily intended to be viewed as art.