Featured in

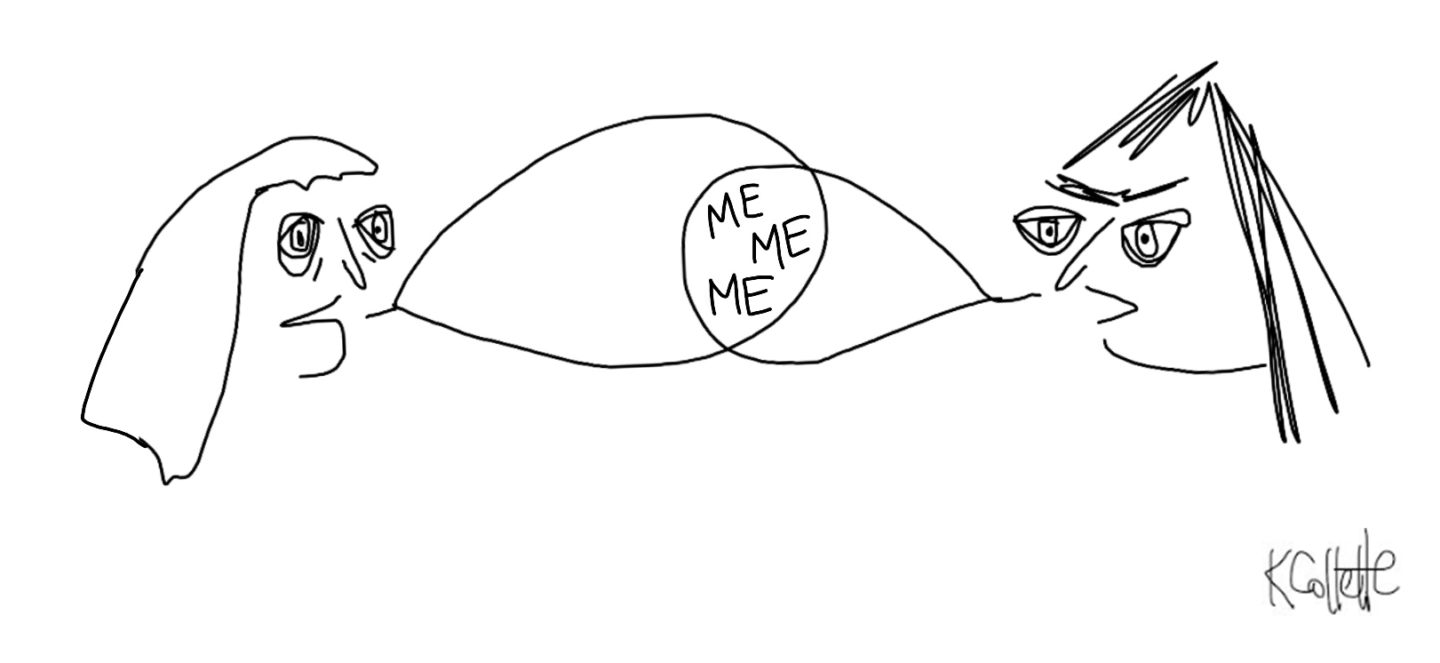

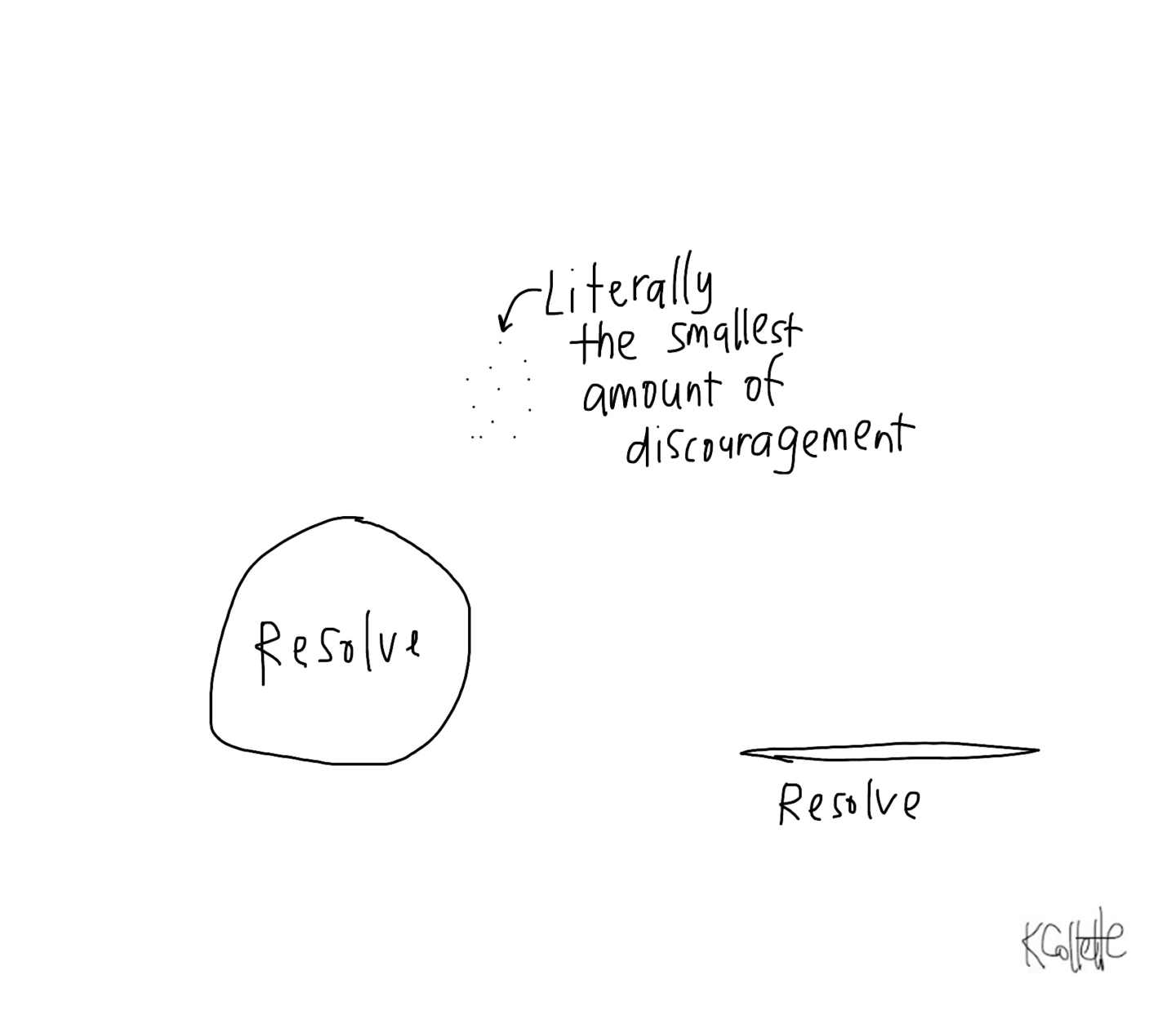

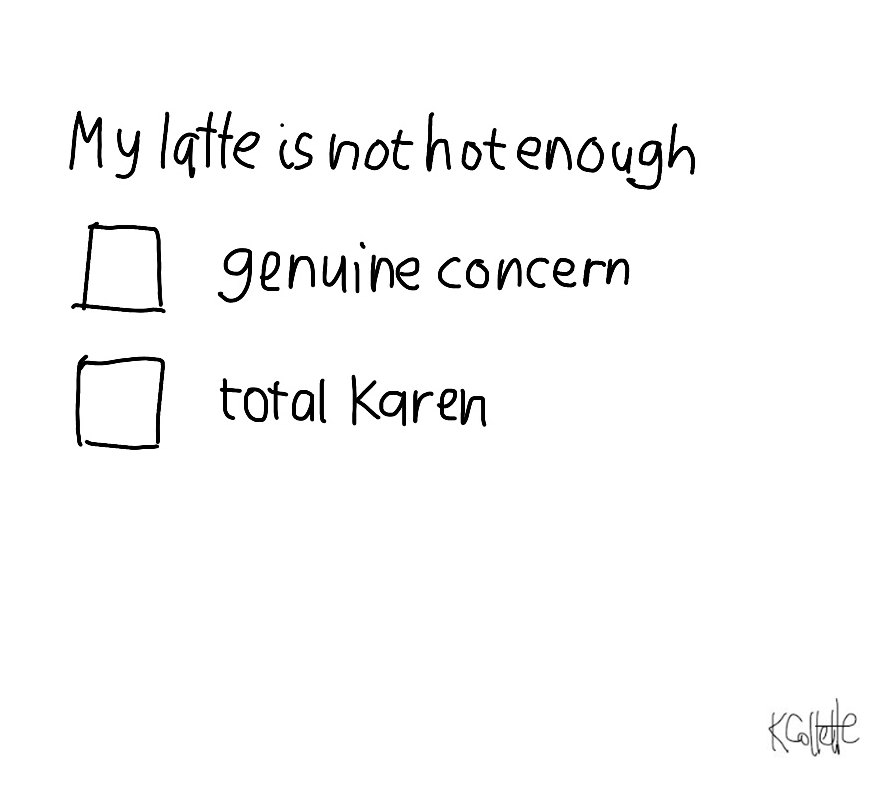

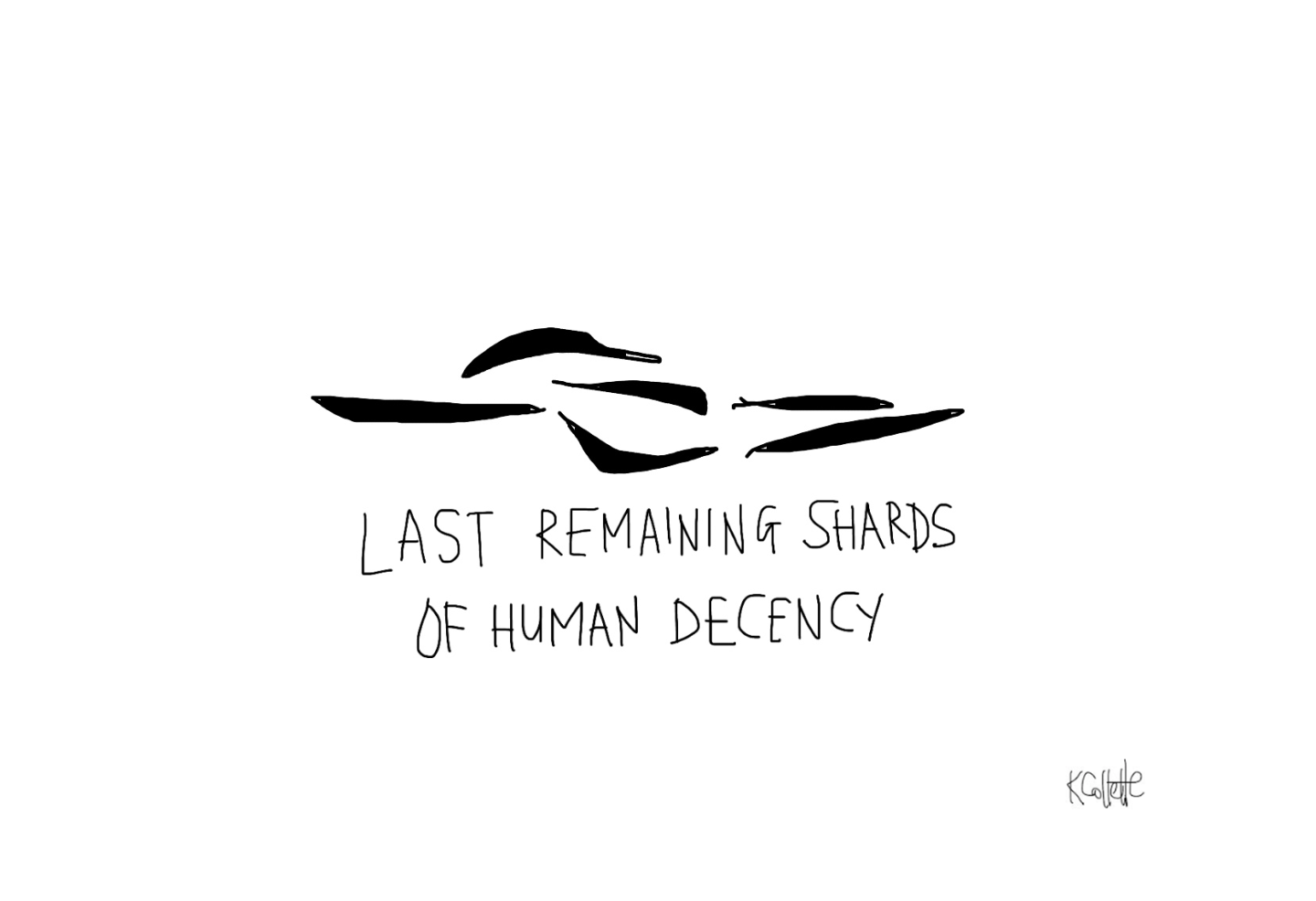

Katherine Collette’s cartoons effortlessly traverse the emotional spectrum of everyday life, from small acts of love (when your partner stacks the dishwasher correctly) to big feelings of embarrassment (when you wave back at someone who wasn’t, in fact, directing their wave at you). To celebrate the launch of our latest edition, Griffith Review 84: Attachment Styles, we’re publishing a suite of Katherine’s extremely relatable cartoons. Griffith Review Editor Carody Culver spoke to Katherine about the feelings that fuel her cartoons and the complexities of pursuing a creative life.

CARODY CULVER: You’re a writer, cartoonist, podcaster and writing coach – a woman of many talents! Which came first for you: writing or illustrating?

KATHERINE COLLETTE: Reading, if I’m honest, but then writing. I was a big diary and letter writer as a kid, though no evidence of this remains, sadly. I ripped the pages out of all my diaries almost as soon as I wrote them, out of fear someone would read them. The letters, I sent.

In terms of drawing, my two best friends and I drew stick-figure cartoons of ourselves in our teens. Most of them centred around the desire to be cool, well dressed, get boyfriends etc. (and our failure to achieve this).

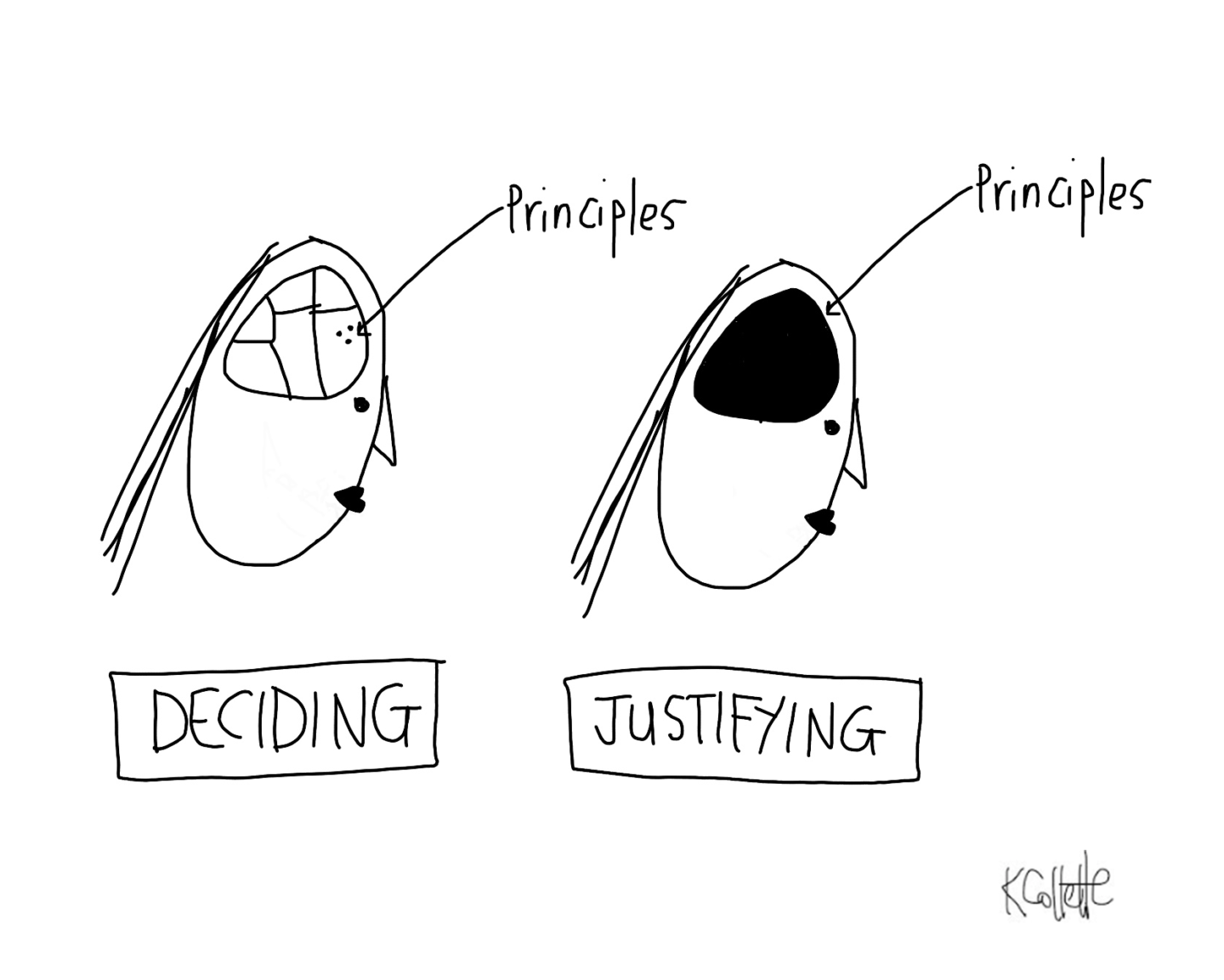

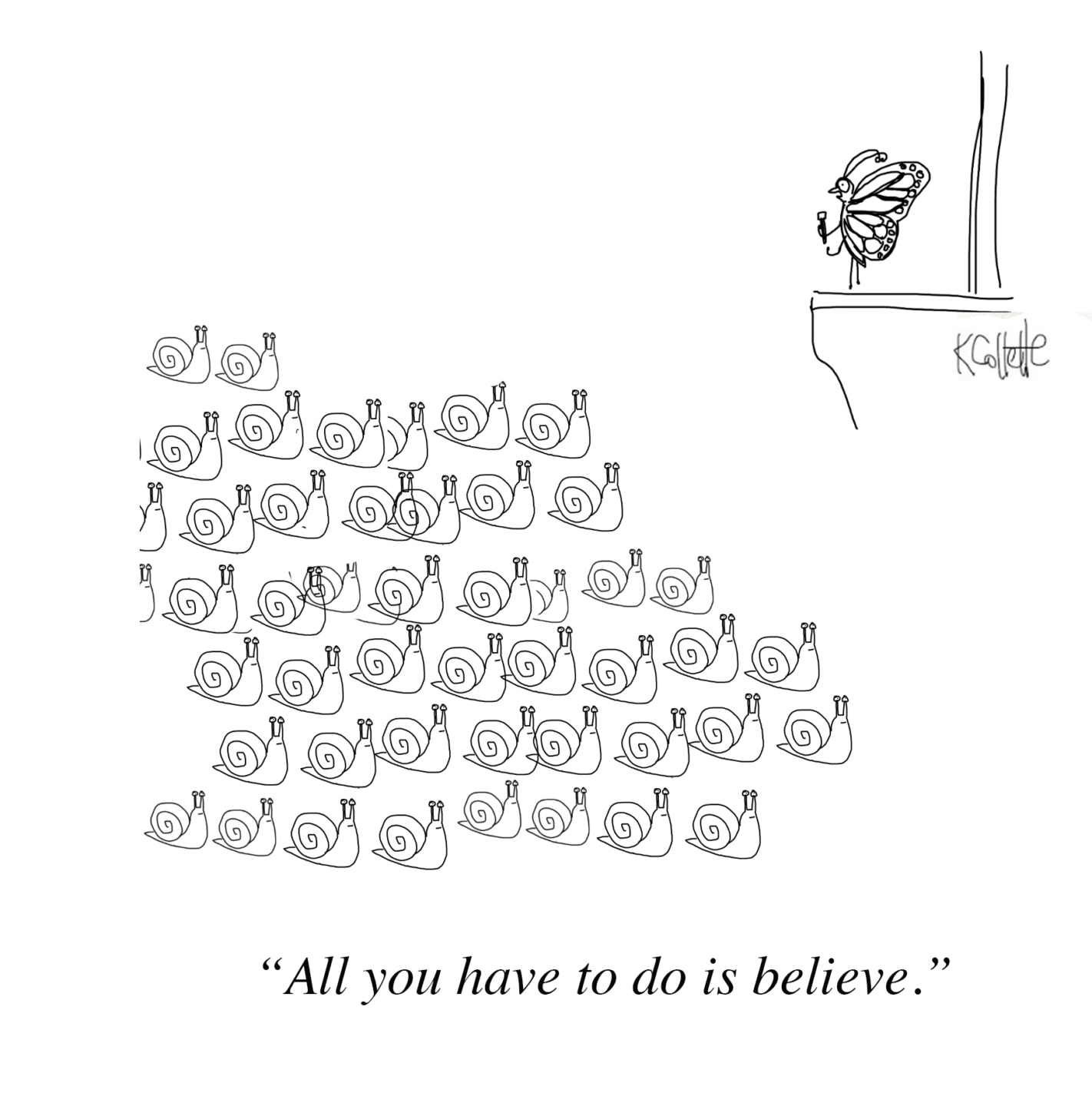

CC: Some of your fabulous cartoons that we’re publishing in Griffith Review tap into feelings that are likely to be familiar for many writers: anxiety, vulnerability, self-belief, uncertainty and embarrassment (hello darkness, my old friend). Does cartooning help you make sense of these feelings in the context of your own creative endeavours?

KC: Absolutely. There are so many weird feelings in the writing space and such a sense of connection in realising other people feel them too. What I like about cartoons is how they distil a feeling or thought to a single moment or image. There’s something therapeutic about figuring out the essence of a thing.

CC: The love languages cartoons are especially fun – what prompted you to reimagine the love-languages concept?

KC: The idea of love languages is very sweet, but I feel sorry for people in the ‘receiving gifts’ category. Is this really a love language? Sometimes I think when categories are made, there aren’t enough and they have to put in a few fake ones to make the others sound real.

The best expressions of love in my life are tiny things, sometimes so minuscule other people mightn’t even notice them. Like, if you have little kids and you and your partner take it in turns to clean up vomit or do something else that’s unpleasant, both of you know at all times whose turn it is to do the thing. You’re keeping tally in your head. So if it’s my turn and my husband voluntarily does the thing instead, it seems so big and generous, even if the act itself is small. Expressions of love are specific to the context.

Also – my kids ask me all the time for a bite of what I’m eating and honestly, I never ever want to give it to them. I feel like an absolute martyr when I do.

CC: Your podcast, The Next Step, features interviews with all kinds of interesting people – writers, comedians, entrepreneurs – about how to figure out what to do next in life after you’ve embarked on a particular creative pursuit. What drives you to explore the complexities of a creative life as well as living one yourself? Do you find that your work in this space feeds your own writing and illustrating?

KC: I am obsessed with how people think about what they want and what they want to achieve in life. I am at once deeply sceptical of vision boards, affirmations and manifestations – and also cannot get enough of them. I don’t go to psychics, not because I don’t believe in them but because I believe too much.

Writers think we’re special, that we have a particular variety of neurosis, but talking to comedians and entrepreneurs and others, this isn’t true. The hard bit about doing anything, be it writing or comedy or business or sports, is not the doing of the thing, it’s the thoughts and expectations and disappointments and feelings of rejection, futility etc. etc. that come along with it. I feel like the sporting and business worlds are across this. Sports psychology is all about how your brain impacts your performance and that’s been around for ages. I don’t see an equivalent in the creative space, so I’m trying to understand what people in other fields do and use it myself. The podcast is self-interest, really.

CC: Your first book for middle-grade readers comes out this year, and you’ve written as well as illustrated it. Can you talk me through the process of illustrating a story? What comes first for you – words or images?

KC: I got the idea of drawing cartoons by doing morning pages. Morning pages are a creative practice from The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. You handwrite three A4 pages of stream-of-consciousness writing for twelve weeks. They’re astonishingly useful. You find the same few things keep coming up, over and over. When I did morning pages through Covid lockdowns, I kept writing how much I wanted to draw cartoons like the ones I did in high school. So I did. I was working on my middle grade at the time and every day after writing, I’d draw one cartoon. Sometimes it would be tangential to the words, other times it would replace the words. The only rule was it had to be a single, standalone panel. It was fun.

While I love cartooning, I find the drawing part hard. It drives me crazy how terrible I am at it. I’ll have a concept I love but will be hamstrung by what I’m actually capable of depicting on the page.

CC: Your standalone cartoons are extremely relatable – the jar of waves, in particular, made me feel very seen (pun intended!). What’s your process for creating these cartoons? Do you keep a list of concepts you think might translate well into visuals, or is it a more organic, ad-hoc process?

KC: Firstly, thank you.

I have a background as an engineer. Engineering is all about taking a complex thing, breaking it down into its smallest parts, then working out the connections or sequencing between the parts. Cartoons are kind of the same. I like trying to apply a sense of logic to an emotion or feeling. At the core is a single, relatable truth, like ‘the feeling of embarrassment when I think someone is waving at me, I wave back, then realise they weren’t waving at me in the first place’. The fun bit is in figuring out how to represent that.

It’s like: I have received a wave that was intended for you. Perhaps I am collecting the waves that were not intended for me. What does a wave look like? Where would I put it? And so on.

There’s a level of trust in believing you’re communicating your concept. I have such an urge to caption every cartoon with an explanation of what the point is.

Image credits: all courtesy of Katherine Collette

Share article

About the author

Katherine Collette

Katherine Collette is the internationally published author of two novels for adults, The Helpline and The Competition. She’s written and illustrated (in cartoons) the...