Featured in

I came to surrounded by recipe books, celebrity memoirs and wall-to-wall Colleen Hoover. My last memory was searching, to no avail, for a copy of Jennifer Down’s Bodies of Light in my local bookstore. I registered a rack of bike pumps across the aisle, rows of men’s socks the opposite way. Nearby tweens were giving me the side eye – and then I knew. I was in Kmart.

WHERE I GREW up, in north-west Sydney, there was only one bookstore, which diminished in quality through various rebrands over the years. Whenever possible, I slipped from my mother’s side to peruse the book aisles of Kmart, which was happy to be a major recipient of pocket money for my age group. I exhausted my school library. After that, I wielded the precarity of my interest in reading – an interest that was hard won and cherished by adults in my life – to deploy my parents to libraries across the shire. It never occurred to me that it was difficult to find books. In my teen years, I resorted to reading ePubs on my 12 cm x 6 cm iPhone 5.

Then, in university, I moved to the Eastern Suburbs: there were three community libraries within two blocks, a public library, second-hand books in the millions in Vinnies, and so many independent bookstores a bus ride away that in five years I did not exhaust them. That’s to say nothing of the nearby Kinokuniya and a three-storey Dymocks, like booklovers’ Edens.

My reading list transformed. It grew exponentially in quantity and quality. I read more women writers, I read across race and genre and language, I read books I didn’t know could exist, and then I felt emboldened to write a book I hadn’t previously known could exist. Part of it had to do with natural growth. Part of it was that I spent so much time – for the first time – in independent bookstores, which featured personalised recommendations showcasing writers overlooked by bestseller lists, online algorithms and the Department of Education.

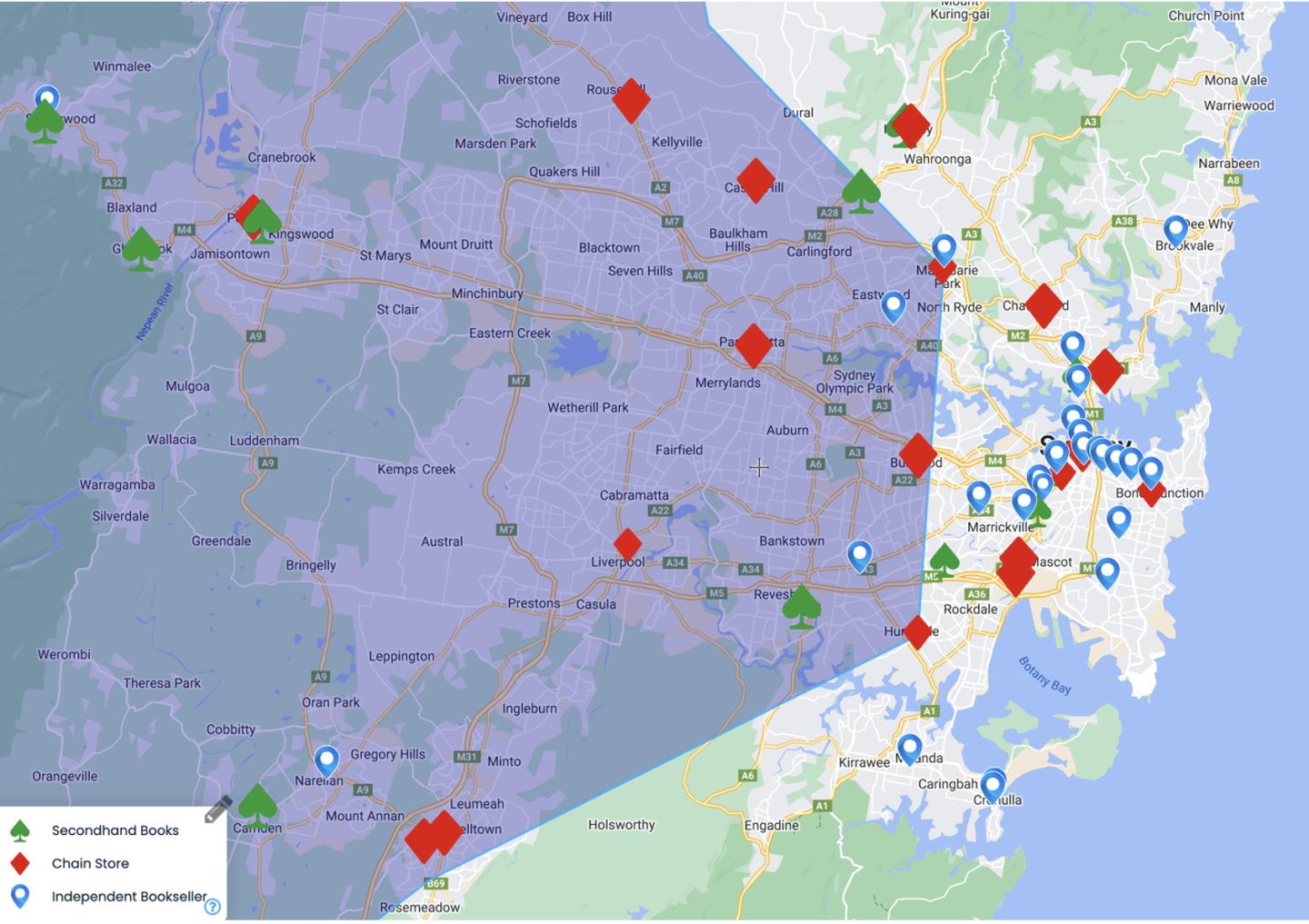

Eventually, I relocated to Sydney’s south-west. For a month, I searched fruitlessly for a book joint. At first, I thought I wasn’t looking hard enough. I searched so far I ended up in the Blue Mountains. It was only after I found myself, after so many years, back in that Kmart book aisle, that I sat down and made a map:

* The blue shaded area is a rough outline of Western Sydney. I have not included specialty (such as religious, educational and new-age) bookstores.

In a twenty-kilometre radius from where I live, there is only one bookstore. In all my surrounding suburbs, there are none. The nearest independent bookstore is almost thirty kilometres away. On the eastern half of my map, across the blue line, there are so many bookstores that the pins blot each other out unless you zoom in to go street by street.

Western Sydney is home to half of Sydney’s population, and 10 per cent of the population nationwide. In other words, at least 10 per cent of the nation lives in a metropolitan area with almost no bookstores.

But the real kicker is this: in Western Sydney, it’s almost impossible to buy books by authors who write from and about Western Sydney. Of all the Western Sydney authors I conjured off the top of my head, my local bookseller (a chain) stocked two.

All the programs and collectives and mentorships directed at the supposed hotbed of literary potential in Western Sydney – what are they for, if none of us can sell our books here and the community we write about is not expected to read? Why have I spent three years writing a novel that won’t reach the people to whom it is dedicated?

THE IDEA OF spatial inequality is not new. Neither is the concept of ‘book deserts’, nor the pitfalls of suggesting public libraries and ebooks as alternatives to physical book ownership for low-income families. And yet my online quest for enlightenment regarding Sydney’s bookstore disparity yielded unfulfilling fruits.

So I did what anyone who has shaped their identity around Nancy Drew would do, and embarked on some old-fashioned investigative journalism by speaking – in-person! – to three booksellers across Western Sydney. Their responses boiled down to this:

1. ‘Western Sydney can’t read.’

All three booksellers cited the region’s culturally and linguistically diverse, low-income, high-migrant population as evidence of illiteracy proportionate to bookstore scarcity. The temptation of a Murdoch-media-addled mind is to accept this, until one realises it would mean half of Sydney is illiterate.

The facts, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, are that 85.8 per cent of Western Sydney residents speak either only English or another language as well as English well or very well. For Greater Sydney, the same statistic is just slightly higher at 88.6 per cent. Nationwide, a study of NAPLAN results found 93 per cent of Year 5 students with a language background other than English were above the minimum standards in English literacy, an achievement that rose to merely 96 per cent for their classmates with an English background.

During one of my bookseller interviews, an Arab-Australian security guard about my age came up to the counter and overheard our conversation. ‘Education levels are much lower out here. Research it. That’s why,’ he offered, while paying for no less than ten books. O, brother, are we so severe upon our own race?

2. ‘Western Sydney can’t afford books.’

This assertion by the booksellers I interviewed was immediately, and bafflingly, followed by the sheepish admission that their Western Sydney stores were their chains’ most successful outlets in Sydney. When I queried them on the contradiction, they attributed their success to being ‘the only bookstore for miles’. Actually, it’s more consistent with the fact that, although Sydney’s wealth is undoubtedly concentrated in the inner city, a weighted survey of Australian readers conducted by the Australia Council for the Arts found that reading frequency is not significantly stratified by income.

The axiom that books are ‘items of leisure’ unsellable in low-income areas relies on the assumption that either people in Western Sydney spend no money on non-essential items or that other forms of leisure offer them greater value for money. The former assumption collapses within minutes if you step into Bankstown Central, which is packed like a sardine tin with shoppers spending at jersey joints, perfumeries, specialty boardgame stores, restaurants and jewellers – yet in that entire suburb there is not a single bookstore. The latter assumption, closer to the truth, is not a Western Sydney problem. The Angus & Robertson outlet in Bankstown closed not because it was in Bankstown but because the franchise folded nationwide. It was a casualty of online mega-corporations, and what Ben Brooker, in a wonderful Kill Your Darlings essay about the affordability of books, called the ‘vicious squeezing of our leisure time by the demands of life under advanced capitalism’. If there is paucity, it lies not just in spending money, but in attention. Speaking of which:

3. ‘Western Sydney does not care about art.’

At some point in all this, I had a thought: where am I supposed to launch my book? The independent bookseller I interviewed was keen for more book launches out west. ‘But,’ she said, ‘authors are afraid to come here. They feel like no one will show up. To eastern Sydney, we’re basically overseas.’

If Western Sydney doesn’t show up for art, what of Bankstown Poetry Slam, a local art powerhouse that boasts an audience of 300 each month? What of the 400-plus tickets sold for the inaugural Sydney Muslim Writers’ Festival (SMWF) held last year in the Bankstown Arts Centre? I was on a panel for said SMWF, and admittedly I too was convinced no one would show up – but allocated seating ran out within minutes and people had to stand at the back. I faced a room overfull of people who wanted to see their own future imagined.

Between 2015 and 2023, the half of Sydney the people in that full room calls home received only 3.4 per cent of federal arts funds; eastern Sydney attracted 23.5 per cent. If art is indeed undervalued in Western Sydney, who is doing the undervaluing?

DRAFTING THIS ESSAY, I thought I’d stumbled upon an undiscovered headline, but publishers already know all about the lack of bookstores in Western Sydney. One told me, ‘It’s not a glamorous place to find your novel, but if you want to reach those communities, you’ll have to sell in Big W.’ The lack of glamour doesn’t bother me, but Kmart and Big W hardly seem the places to foster a love of reading.

So where is the place to foster this love? If consumers are guided by value judgements, how does one convince Australians that books are worth their time? Certainly not in schools, where HSC-prescribed texts are wildly unreflective of Western Sydney’s demographic, and where study of non-white authors tends towards themes of ‘belonging’ (which sounds just as boring to me now as it did way back when).

This community, imagined as being incapable of reading, or at best uninterested, has never been on the receiving end of an adequate effort to capture their interest in literature. There are Western Sydney writers working not only to serve that interest but to expand it imaginatively. Where is our place on the shelf? I am looking for it on a map half empty.

Share article

More from author

To write, perchance to dream

In fiction, dreams are a useful tool. They are the writer’s divine intervention. Like the famous opening of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, they can reveal the past in eidetic detail. They can make the murmurs of the subconscious plain. Catherine Earnshaw dreams she leaves Heathcliff to enter heaven, only to begin weeping to come back to earth.