Featured in

- Published 20170801

- ISBN: 9781925498417

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

I WOKE UP at about midday. My head was still heavy from the drinking and some vaguely remembered sexual activity of the previous night (with whom I was also unclear about; my memory seemed to have dissolved in the vodka). My left eye was watering. I tried to open it, but the eyelashes were stuck together and I had to mop the pus out. I rinsed my eye with lukewarm water, but to no effect. The world still appeared blurry. Now this was a problem. While I earned my living as a journalist, I was also working towards a solo exhibition of my photography. I would call it Views of Tel Aviv, but really my focus was on women. Beautiful women. The streets of Tel Aviv were lousy with them and, for spontaneous effect and to avoid trouble, I photographed them without their noticing, taking long-distance shots using a special lens that cost me a fortune.

The phone rang. ‘What’s up, Jonathan?!’ It was Surasky the Creep. We worked together in a small yet well-regarded magazine, Non-Stop City. We had started there around the same time, six years before, but he was the editor’s pet and his position was way more senior than mine. In fact, the positions of all Non-Stop City employees, including the cleaning lady, were more senior than mine. I had still been a freelancer until three months ago, when Igal Sobol, the editor, had finally granted me a very part-time position. ‘So that you’ll stop nagging me,’ was exactly how he had expressed himself when he had appointed me assistant to the magazine’s food and wine writer. My job was to write the weekly column that reported on industry-based gossip. I even started receiving invitations to restaurant openings and media releases addressed in my name. I would arrive at the office and the receptionist would say: ‘Jonathan, I’ve got some mail for you.’ Mail for you… What wonderful words!

I wasn’t even two weeks into my new role when my promotion came under threat. Apparently I had misspelled the name of some seafood restaurant at the port (I still maintain I had copied whatever had appeared on their PR brief). The owners threatened to withdraw their advertising. Sobol summoned me into his office. It was the seventh time since I had started working at the magazine that I had been invited in there. I didn’t know yet about the restaurant scandal. I thought that perhaps now that Sobol could see what a fine job I was doing with the column, he would propose that I step up and replace the food and wine writer. I was so nervous as I walked into the editor’s tiny room, crammed with books and old New Yorkers, that I could barely say ‘Good morning’. My humiliation increased once I noticed Surasky was there too, his fat ass comfortably spread upon Sobol’s desk as he puffed on his cigarette with his irritating familiarity, as if he was the editor’s girlfriend or something.

Sobol seemed mad. He waved a piece of paper at me, apparently a letter from the restaurant’s lawyer, and muttered: ‘It’s clear that you can’t write, but I didn’t realise you can’t read either!’ Surasky giggled. I felt my face burn. But I did know I could write. I did. I just never knew how to show it amid the mindless tasks Sobol assigned me.

I probably looked seriously miserable, because even Igal the Terrible (that’s what everyone called him behind his back) took pity on me and said: ‘Tell me, Jonathan, why do you need this job? Why have you been torturing yourself, and me too, for so many years? And for such a miserable salary. Why don’t you change your profession while you’re still young? The thirties are the new twenties, they say these days.’ At that, he looked almost human. Even his thick eyebrows softened. But I said nothing. What could I say, particularly with Surasky there? I was sure neither of them – who, I gathered, had grown up with parents who drank Italian wines and talked Proust over breakfast, or something along those lines – would get how devastating it would be to abandon my childhood dream. Where I come from, a provincial port town where most people survive on pensions or salaries from work at the docks and meat factories, I’ve seen many people do exactly that, their little worlds getting smaller and smaller with each year passing year, and I was determined not to end up like them. Not that my life was going particularly well either, but at least I had one thing I could stick to: the knowledge that I never gave up. At least not yet.

For reasons unknown to me, Sobol let me keep my job.

‘HEY MATE,’ SURASKY now roared down the phone, with that impersonal benevolence of his that always got on my nerves, ‘where’s that article about the footpaths? You said it’d be here in the morning.’

‘Why, what’s the time now?’ I asked.

‘Now? It’s 1 pm, mate, and the old man’s not happy.’

‘Oh…’ The print deadline! I was beginning to panic, but the main thing was not to show this to the Creep, to preserve some dignity. And anyway, this article I had laboured on for some weeks was almost finished to my satisfaction. ‘Okay, just let me fix a few sentences and I’ll email it straight away,’ I said with as much nonchalance as I could manage.

‘Listen’, said Surasky with apparent satisfaction, ‘it’s too late now for this issue. So don’t worry about it. That’s what I called to say.’

‘But… I’ll send it anyway. For next week.’

‘Nah, forget it. The old man’s dropped the idea. Next time, mate, make sure you don’t miss your opportunities.’ At that, Surasky slammed down the receiver.

Outside the rain was welling up, the sky booming. My little studio apartment was dark, even though it was daytime. The place smelled musty. I felt like shit, but I had to get out of there before I went out of my mind. That article – about the dreary state of Tel Aviv’s almost non-existent footpaths, particularly in the city’s poorer southern part where gutters ran open, overflowing, tripping up the ubiquitous stray dogs and junkies – had been my chance to get back into the serious reporting I used to do when I was in my teens. What I really wanted from journalism was to work gonzo style, examining the world through the prism of my experience. This was where my passion lay (and when I couldn’t realise it at Non-Stop City, photography became its sublimation). I had tried to write like this in my article about footpaths in Tel Aviv and hoped that publishing it would have led to more feature assignments and that eventually I’d be only writing urgent stuff, in my own voice, rather than copying shit from media releases.

I was proud of this article; it reminded me how good I used to be when I had worked for a popular youth magazine as a young reporter. Then I had turned eighteen and gone off, like everyone, to do the compulsory military service. Three years on, once the stint in the army was over, I wasn’t anybody’s golden boy anymore. The world of adult media was way more complicated and it confused me. I lacked the connections and easy sophistication of the journalists born and bred in Tel Aviv. It didn’t take me long to realise I was no good at the politics of the job. Even though it had been years since I left my rough-and-tumble town and moved to Tel Aviv, I was still a foreigner in this city. I didn’t know how to lick the arses of my editors properly, while they, in turn, found me lacking.

As the years went by, I came to accept my chronic failure. But this time I felt differently. I knew my article was good. The fact that Sobol considered me an idiot shouldn’t prevent me from getting closer to my dream. I’d try the competing magazine, Our City, no matter how much it might piss off Sobol. This sense of determination – new for me – felt exhilarating. Of course, I hadn’t the slightest idea of how things would turn out.

ON MY WAY to see the editor of Our City, despite the fog on the streets and over my left eye, I still managed to see her as I neared the bus stop. How could I miss her? Tall and slender, she was the kind of a woman you’d expect to see on the Fashion Channel, not in your neighbourhood. But there she stood, strikingly beautiful, the fog enveloping her as if it was her shroud, waiting for the bus with a large bag slung over her shoulder, alongside an old man dressed in a fedora and a tailored coat that had surely seen better days.

I stepped behind a tree before she had a chance to notice me. I took in her long dark hair, caramel-colored skin, high cheekbones and aquiline nose – the only glitch in her otherwise flawless features. This was exactly what I wanted for my exhibition and so far hadn’t found: beauty with a flaw, but a flaw that actually rendered her even more attractive. She would be my metaphor for Tel Aviv, with all its sweaty, bedraggled magnificence.

I pulled out my camera. But it was difficult to focus on the woman, as she was restless, fidgety. She seemed disoriented. I adjusted the long-distance lens. Now I could see her face clearer. She had an odd gaze, intense and yet aloof, as if her intensity was directed inwards. Her mouth was contorted. She could have been talking to herself. I began to realise that my interest in her went beyond my interest in Tel Aviv. There was something unsettling about this woman that reminded me of myself. I wondered why she appeared so desperate. Had her lover just left her? But then, women like her were meant to be the deserters, not the deserted. There must be a good tale in this. I contemplated including story captions with my photos, and began snapping away.

EVEN NOW, WHEN I try to remember what happened next, it comes back as vague as that milky autumnal afternoon. I can only recall fragments, snapshots: her gorgeous face distorting with terror once she noticed the flash of my camera, her long arms probing frantically inside the enormous bag, a fountain of running flames, the smoke, the old man’s fedora flying through the air towards me.

My memory becomes more coherent only with the (prompt) arrival of the ambulances, sadly adept at responding to such occurrences. ‘You got off lightly,’ a young paramedic with a pirate earring in his right ear said as he treated my scratches. ‘Tell me,’ he added, ‘aren’t you that reporter who interviewed us a few months ago?’

I nodded.

‘So what happened to the article? Why wasn’t it published?’

‘Because my editor doesn’t like me,’ I mumbled before passing out.

When I regained consciousness, I found a prominent army general by my bedside awarding me a certificate for foiling an act of terror. I said a feeble ‘thank you’, even though I hadn’t foiled anything really. I was just not careful while taking photos and she must have got a fright and accidentally set her bomb off. But I had no energy to argue. I remembered a torn arm somersaulting through the air and passed out once again.

At that time there had been numerous terror attacks throughout the country and many people had been killed. A certain indifference seemed to have settled over many of us; apparently, even fear has its limits. So there wasn’t much fuss made that day when the media outlets reported that a large-scale disaster had been prevented at the last moment, when a passerby had identified a suicide bomber and stopped her from boarding a bus full of passengers. There were only two dead and one slightly wounded. One of the dead was the terrorist.

The entire affair would probably have been forgotten quickly were it not for a reporter from one of the dailies, Yediot Ahronot, who came to see me in the hospital later that night. He noticed the camera on my bedside table and asked whether I was a photographer. After I told him my story, he turned pale.

‘Am I the first to find out what really happened?’ he asked.

‘I guess so,’ I said. ‘Most of the time I was unconscious.’

‘A woman,’ he said. ‘A beautiful woman. A woman… I’ve got to make a call. Do you mind?’

The reporter returned quickly, his eyes sparkling. ‘Allow me,’ he said, ‘to offer you fifty thousand shekels for the exclusive rights to the photos you took.’

My lost senses came back at once. After brisk bargaining we agreed that for this amount Yediot Ahronot would receive exclusive publication rights to my photos, but I would be able to use them for other purposes, including my hypothetical exhibition.

Despite the nausea I experienced, I immediately felt better. In my sorrowful financial situation, fifty thousand shekels would make a difference. I began planning how to use the money best. Even then, I still didn’t have a clue what the future held.

THE NEXT MORNING, I found the entire front page of Yediot Ahronot taken up by one of my photos of the woman. It turned out that the reporter was a most industrious professional. Overnight, he had pieced together her entire life. Jasmine was her name and her story occupied the following two pages along with photographs from her more distant, less sinister past. Now that my eye healed and my vision was clearer, the woman made less of an impression on me. There was something common, even dull, about her highly arched brows and capriciously pouting mouth.

I found out Jasmine was of Palestinian origin, but had been brought up by relatives in Paris and had worked as a lingerie model for a major fashion house. At some stage she had fallen in love with a member of Hamas, who was on a lengthy visit to France. The man capitalised on her feelings, got her hooked on heroin, then convinced her to blow herself up for the sake of both him and the native land. ‘A shocking deed,’ wrote the reporter to ensure this point wouldn’t be missed by his readers, ‘to use this innocent beauty in such a way.’

On the next page I found an article about myself, replete with expressions such as ‘the courageous man’, ‘the knight with the camera’ and ‘the pride of the Israeli press’. I was praised for my vigilance and even for a ‘gift of prediction’. ‘This exceptional person who saved many people’s lives,’ the inexhaustible reporter continued, ‘raised the flag of our media high.’ In all those pages there was only one, brief mention of the old man’s death. For some reason, my predominant thought after reading it (competing with an involuntary flashback to the airborne fedora) was that I must visit Non-Stop City.

Later that day I was released from the hospital, intact yet still dizzy. The weather had improved and the sun was now shining upon the uneven, narrow footpaths of Tel Aviv, which were covered almost in their entirety with café tables and illegally parked cars. I went to buy cigarettes. The television in the grocery store was on, showcasing photoshopped stills of Jasmine. To my astonishment, I realised it was the CNN channel. I couldn’t recall that year seeing any other CNN reporting of the terror attacks in Israel, even when they were at their peak. Now I heard the presenter asking a political commentator what he knew about the relationship between fashion models and terrorism. In the background to their conversation I recognised an image of myself, lying in the hospital bed. Seeing me on the screen, the grocer refused my money. In exchange for the cigarettes, he just wanted to know whether I had seen Jasmine’s panties as the bomb went off. That is, if she had worn any.

At home I checked my mobile phone. I had twenty-two messages, eight of which were from the producer of the television talk show The Circle. I had been invited to appear there on that very same evening. I called back to say ‘yes’, and during the drive to the television studio kept trying to work out how what was happening to me related to my childhood dream. As I waited behind the scenes along with the minister of foreign affairs, an Ethiopian migrant with albinism, and two magicians from the Moscow Circus, I watched the opening story of that night’s news broadcast. ‘We’ll be discussing the most recent suicide bombing,’ the presenter said. The discussion proved to be predominantly an interview with Jasmine’s hairdresser.

THE NEXT DAY, it was impossible to go anywhere without seeing Jasmine. It was as if she had been resurrected. The women’s magazine LaIsha published an interview with her French relatives, who discussed in colourful detail her rendezvous with the terrorist and descent into drug addiction. On primetime radio, a right-wing politician denounced Palestinians for exploiting their women, and a left-wing activist said Jasmine was a victim on the road to peace.

That afternoon, the personal assistant of someone called Mr Weiss rang me up. She said Mr Weiss owned a company that manufactured toys. He wanted the commercial rights for my photos of Jasmine in return for two hundred and fifty thousand shekels. I signed the contract. Some weeks later a new toy hit the market, becoming an overnight success: a suicide-bomber Barbie fashioned in the image of Jasmine with a large sparkly bag slung over her shoulder and pink toenails. After she exploded you could reassemble her.

Despite the money and the publicity I received, I didn’t feel happy. Jasmine’s dead face haunted me during my waking hours, staring at me from newspapers, televisions, magazine covers and the sinister Barbie dolls’ faces. At night I dreamed of the elegant, if somewhat shabby, old man.

Soon I began receiving job offers from various media outlets. I knew I was supposed to feel proud, that my dream was indeed coming true. But it seemed my potential employers just wanted the name of the ‘pride of the Israeli press’ on their list. I couldn’t decide what to do until Yediot Ahronot offered me a job as their correspondent in Australia. That offer seemed the best solution to my situation. At least I wouldn’t have to face Jasmine everywhere I went.

Just before leaving Israel, I decided to visit Non-Stop City. I just couldn’t leave without witnessing the sorrowful face of Sobol, who must now be full of regret about not appreciating me at the time, missing the chance of his life.

The first thing I noticed when I entered the office was the admiring look on the face of our normally tough secretary. When I was still working at the magazine, she enjoyed humiliating me at any opportunity. Now she timidly asked for my autograph. It was only then that I realised the true extent of my success.

Feeling victorious, I proceeded to Sobol’s office. This time my knees didn’t buckle. I even thought for a minute about kicking his door open and roaring: ‘Hello, old man! Know what? You can stick all your fucking restaurants up Surasky’s fat ass!’ Then I’d spread my Superman cape and fly out of the editorial window away to the delicious foreignness of Australia.

I pushed the door open to the familiar sight of Sobol with his Brezhnev-thick eyebrows, looking busy at his computer, and Surasky perched on his desk, insolently blowing smoke in Sobol’s face. Just then I realised that if Sobol asked me now to replace Surasky on his desk, then to hell with Australia, even if Non-Stop City was a publication known only to a handful of so-called intellectuals.

Upon seeing me, Sobol said, as usual: ‘Yes, Jonathan, did you want something? Be quick, please, I’m in a rush.’ And Surasky giggled in his usual way. I, too, acted in my usual way. I bit my tongue. For a minute I stood still, hopeful in my totally idiotic fashion that Sobol might change his mind, might ask me to stay, or at least say something about my ‘heroism’. He didn’t. I shuffled out through the door.

MY NEW JOB is good. I really can’t complain. I now live in Sydney, and what I once did purely for pleasure I get paid for here. I still follow beautiful women with my camera while trying not to get noticed, but now it’s the famous ones I’m after. Cate Blanchett, Elle Macpherson, Kylie Minogue. The editors are satisfied with my work. I have my own column called Celebrity-Schmelebrity that, I hear, is popular back home.

I’m very busy here. These famous women are energetic folk, always doing something the public wants to know about. Only today, eight months after my arrival, I finally have a day to myself. So here I am, in my rental apartment overlooking Sydney Harbour’s brilliant beauty. Both inside and outside of my place, the surfaces always seem to sparkle. I’m lying down in this mirror maze on a leather-brown recliner, which can do so many things that I feel bashful in its company. From my large window I watch the splendid rain, dark and sleek like a panther. I stretch my legs out on the cushions, which also exfoliate, and listen to the rain’s purr, contemplating whether now I’ll have a better chance to resubmit my article about the footpaths in Tel Aviv.

Share article

More from author

At the Russian restaurant: Audio edition

MediaListen to Lee Kofman read aloud her short story 'At the Russian restaurant', a vivid tale of love, belonging and alternative lives. This story appears...

More from this edition

Sound, drums and light

EssayIN MY LATE-TEENAGE years, I found myself for a time hovering on the border of bogandom. In those long-gone days of the mid-1980s, the...

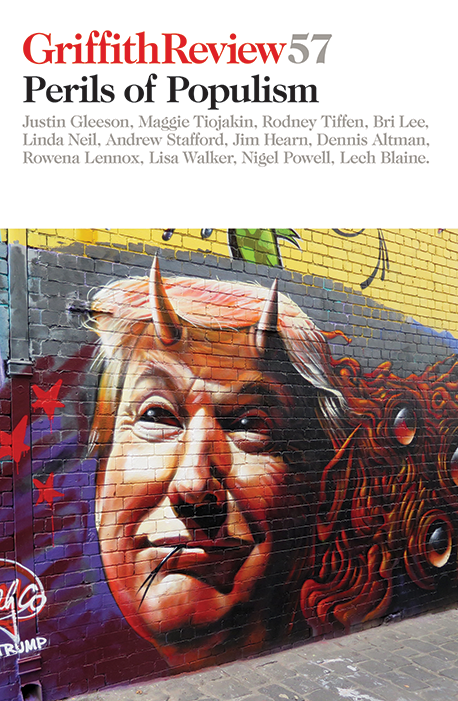

So you want to rule like an autocrat?

EssayNOTE FOR CANDIDATES The word ‘populist’ has lately come to mean white nationalist, alt-right blogger, neo-fascist and so on. These labels are imprecise. So we’ve...

Sous chef

PoetryThey have to go. – Trump This is how I remember you: Thursday nights, stray curlsstrong arms, beads & masks, stretch pants, your brown skinso...