Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

BETWEEN 2016 AND 2017, a series of First Nations regional constitutional dialogues were held across Australia. These dialogues led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and they were resolute in their rejection of ‘reconciliation’ as an appropriate framework to apply to Australian conditions. According to many who participated in the dialogues, reconciliation is the wrong framework, as it assumes a pre-existing relationship: as the Uluru Statement from the Heart puts it, we have never met. The proper framing of the relationship between First Nations and the Australian people is a starting point, an invitation to meet – and this is the vision of the Uluru Statement. In this way, the delivery of the statement by those First Nations peoples gathered together at Uluru on 27 May 2017 traversed the language of reconciliation after decades of trite utterances and a steely-eyed focus on citizenship rights and Indigenous engagement in the market economy to the exclusion of truth and justice. While employment compacts have proliferated, signed in the name of reconciliation, our people have become sicker and less educated while child removals and incarceration rates have skyrocketed.

The confused and asymmetrical way reconciliation has proceeded in Australia has led to a multitude of misconceptions about reconciliation and much bombastic rhetoric around truth-telling. Words such as ‘reckoning’ reveal some of the grandiloquent discourses on truth-telling and the reality of a nation at sea when it comes to Vergangenheitsbewältigung – coming to terms with the past.

The modern Australian incarnation of truth-telling that emerged from the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017 came not from dictatorship and civil war, as had truth-telling in the Latin American ‘radical democracies’ of the 1990s, which pioneered transitional justice. Instead, it derived from local people devising local solutions. I grew up in the reconciliation era; I caught the Beenleigh train to Brisbane’s Central Station and participated in Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation activities at the town hall. I watched John Howard turn his back on reconciliation after this legislatively manufactured hard work. Then I studied reconciliation as it aligned itself with the Howard agenda – I was invited to the 2005 National Reconciliation Workshop at Old Parliament House. I was there in 2010 when Prime Minister Gillard appointed an expert panel to consider constitutional reform and I designed the First Nations deliberative dialogues that led to the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Now, as a legal scholar and constitutional lawyer, I’m interested in exploring here some of the conceptual challenges ahead for Australia’s provincial truth-telling industry, who ahistorically insist truth is a pre-requisite to substantive rights, beginning with a general distillation of the findings of truth-telling commissions over forty years. This is important, because nascent truth-telling processes in Australia have charted a course expressly aligned with transitional justice, a global industry of theory and practice aimed at transitioning societies from conflict to democratic peace. It’s important, too, to consider these findings in the context of Australian conditions. There will be a dissonance between problem and solution if truth-telling is not anchored by a proper settlement framework, as outlined by the Uluru Statement. Failure to understand this will render otiose the goals of truth-telling.

THE CONCEPT OF ‘transitional justice’ derives from Latin America during the 1990s, where ‘radical democracies’ emerged imbued with new and revised constitutions that invoked human and Indigenous rights and the recognition and protection of valued and vulnerable constituencies, for example in Chile. This period of constitution-making was ‘radical’ to the West because it involved investing and extending dignity, equality and freedom to the many constituencies that make up a society, recognition of their rights and their voice in deliberation of public policy.

Latin America had been riddled with autocrats and dictatorships for decades and – after civil war and civil conflict – many societies sought a way to transition peacefully from the enmities of past regimes to liberal democratic governance. Although some scholars connect transitional justice to older traditions in Athens or Nuremberg, the theory that came to prominence during this period was the urgency of reckoning with the ‘truth’ of what had happened during civil conflict so that citizens could comprehend the magnitude of genocide or state violence. To witness and live alongside gross violations of human rights can make it very difficult for humans to move beyond that violence. Transitional justice and its institutional manifestation are intended to create maps of ‘human comprehensibility’, as American legal scholar Martha Minow says, so that victim and perpetrator can live in the same community, in the same streets, and work in the same workplaces. Truth processes are intended to allow citizens to help shape a shared narrative that enables people to achieve a sense of peace and security – this, in turn, allows them to trust the state and to imbue state institutions with the threshold of legitimacy required to move forward.

According to the theory, ‘transition’ via a state-supervised or independent process is necessary for perpetrators to be held accountable and for victims’ perspectives to be aired publicly. This leads, eventually, to reconciliation between the victim and the perpetrator in a way that allows transition to a new shared space. Transition also requires broad public education so a society can have a shared understanding of what has happened, why it has happened and ways to prevent it occurring again. It is a field of practice and scholarship that has yielded much expertise and literature and is now deeply embedded in United Nations practice when dealing with post-conflict societies.

The truth commissions we have seen around the world over the past forty years have generally broadly utilised either a retributive justice approach or a restorative justice approach. The retributive approach risks undermining the goals of reconciliation because it requires punishment, and there are many examples where not adopting this approach has led to dissatisfaction among victim-survivors that justice was never met – particularly when those perpetrators return to society as members of the ruling elite. Certainly, this has been a major criticism of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Conversely, the restorative-justice approach is intended to nurture forgiveness and trust in public institutions. This can animate mistrust if there is no punishment for perpetrators of gross human rights violations. In truth-processes worldwide, perpetrators are often left unpunished or insufficiently punished for what they have done.

Another way that truth-telling exercises are challenging globally is when the mandate of the work they are supposed to undertake – whether via commission or tribunal – is too ambitious and raises unrealistic expectations of what can be achieved. This also influences which parties are included and excluded in an exercise, which hampers its legitimacy and can lead to an asymmetrical outcome that exacerbates resentment or anger towards truth-telling processes.

The findings of overseas truth-telling processes have shown that by and large, the co-operation of victims and perpetrators will determine the effectiveness of the truth-telling. This is because the success of transition is anchored in the way they feel they were treated and their story honoured. Academic Jill Stauffer has written about the failure to listen haunting sites of repair. This explains why the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission did not successfully transition. And it explains why in Australia the very organic actions of transition led by First Nations peoples and local communities to recognise sites of massacres and killings, for example, are central to the Uluru vision of truth-telling. When victims are not properly consulted, the process of truth-telling will fail: the victim is central to the process beyond routine consultation in the design phase. There is also increasing awareness of the insufficient recognition these processes give to victim re-traumatisation in terms of cycles of repetition and recitation of past events. The central role the public plays in truth-telling is also critical to public ownership of the narrative, and public investment in a truth-commission process is therefore a worthwhile endeavour for buy-in. This involves targeted ways of engaging the public, from televised and accessible hearings to ongoing communications aimed at walking the public through the various sequences of the truth-telling.

Consequently, the Uluru Statement from the Heart is a novel approach to ensuring the co-operation of the two sides of the historic equation. Its invitation to the Australian people allows Australians to agree with First Nations peoples on the roadmap of Voice and Makarrata and to provide that pathway with legitimacy. But more importantly, by granting First Nations peoples an enduring Voice, there’s also clarity that the truth-telling process that comes well after the referendum is something that all Australians must engage with, not First Nations peoples alone.

It’s fundamental to remember, too, that what follows any truth-telling is vital to the future social cohesion and comity of a nation. Answering the question of what repair looks like by speaking about history and experience is not enough. Decades of truth-telling practice show that criticism coalesces around the availability and distribution of reparations and compensation to victims as well as the overall size of reparation – all of which can discourage victim-survivor participation. Indeed, where victim-survivors do not receive adequate compensation, the chances of achieving reconciliation in mainstream society can be reduced again.

Indeed, transitional justice may not achieve reconciliation due to many other factors, including focus on legal prosecution, survivors being pressured to forgive prematurely or the reality that truth-telling can fracture social cohesion and increase societal hostility. There are many who question whether truth commissions can ever fundamentally elaborate a truth: one current trend in transitional justice holds that participants individually simply do not tell the truth, and another is concerned about collective unwillingness to achieve a sense of social truth. The latter occurs where there is a failure of the process to properly engage the wider community in the exercise of recalibrating national histories or narratives, or when the broader community cannot comprehend the utility of historic truth-telling in an affluent, functioning democracy. Other critics argue that transitional justice mechanisms fail to solve deeper structural problems in a community, such as socio-economic wrongs, structural violence, environmental inequalities or the absence of democracy.

LET’S TURN NOW to the local conditions for truth-telling in Australia. Truth-telling as an institution or mechanism has not been an option for the ongoing constitutional recognition project in Australia because it does not require altering the Constitution. Beyond this, the telling of Aboriginal history in Australian classrooms featured prominently in all the First Nations regional constitutional dialogues during 2016–17, and this focus on history also featured in recommendations by the 2011 Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. The paucity of public monuments of significant Aboriginal leaders or of historical events such as massacres and frontier battles was also lamented during the opening plenary of each dialogue. In these historic constitutional dialogues, the language deployed was more along the lines of teaching Aboriginal history in schoolrooms and the place of Aboriginal history in Australian history. Much of this history is captured in the ‘Our Story’ part of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

In the post-Uluru environment, much potential has been projected onto truth-telling. It has been viewed as a soft target by some governments and organisations who consider it relatively uncontroversial – or at least less controversial than a referendum. Indeed, truth-telling has historically been deployed as a way of avoiding serious structural reform in Australia because governments want to avoid spending political currency on a policy area that cannot elicit either support from a large voting base or donations. There were those, too, who preferred truth-telling because they personally did not seek a ‘Voice to Parliament’ – and this has seen the emergence of some who have fashioned their own influential voice to the government of the day and the bureaucracy in the post-Uluru environment. These cohorts benefit from the vacuum of community leadership after the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, positioning themselves in close proximity to power and to resourcing that favours maintaining the status quo.

Then there are those who fervently believe that truth is required before any treaty can be negotiated. In this, it is important to remember that the reconciliation process initiated thirty years ago was a contrivance manufactured by a Labor government who could not deliver on a promise made in 1988 by Prime Minister Bob Hawke for a Treaty. Framing reconciliation in this statutory framework was a setback and the first iteration of ‘can-kicking’ by the Commonwealth − to avoid delivering the kind of ‘justice’ that is more electorally controversial than a never-ending truth mechanism that rarely animates recommendations that see the light of day. Even so, this structure saw the genesis of the contemporary idea that, in Australia, you need ‘truth before treaty’. In fact there are few, if any, countries globally who have required or mandated a truth-telling process before a treaty is signed. And the three-step process encapsulated in the Uluru Statement nominated Voice, Treaty, Truth in that order for that reason.

The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance describes situations like Australia’s as ‘historical’ truth-telling. Countries in this position require historical commissions in contrast to truth commissions, as these bodies, according to David Bloomfield, Teresa Barnes and Luc Huyse,

are not established as part of a political transition and may not even pertain to today’s political leadership or practices. Instead, they serve to clarify historical truths and pay respect to previously unrecognised victims or their descendants.

This is an important distinction. There are risks involved in loading a truth commission with contemporary manifestations of structural injustice – this could, for example, embroil such a commission in the same policy contestations that plague Indigenous Affairs today. The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC), which ran from 1987 to 1991, did traverse both historical and contemporary inequality – yet even the magnitude of the RCIADIC was not enough to overcome the tendency of commissions of inquiry to become problematic vehicles for change and law reform. Such commissions are highly technical forums that have powers to call witnesses and scrutinise evidence. Their legalism does mean that they can import many of the restrictions and rules for witnesses and evidence that are inexplicable to the broader community – and this can mean that community expectations clash with evidentiary standards because commissions do not have flexibility to move the goalposts, including the terms of reference set down by the state. As was the case with the Don Dale inquiry, the RCIADIC was created from a moral panic in Australia about deaths in custody. However, once the media circus has moved on, it’s hard to sustain that panic. In the case of the RCIADIC, once deaths in custody became connected to colonisation and dispossession and the primary recommendation was about self-determination, the complexity of issue and solution ran counter to broader public sentiment about Aboriginal people: that we are the architects of our own misfortune.

Royal commissions are complex creatures, but this is not about the truth of what is told as much as it is about political will to effect change – and political will is driven by electoral cycles in liberal democracies such as Australia, where the notion of ‘transition’ can be mischievously problematised for the public in the face of a burgeoning Indigenous middle class and business sector. I touch upon this above where I say that historic commissions tend to jar with the narratives that exist in contemporary society about the success of sections of the aggrieved community. Any dissonance between the grievances of yesteryear by a group and the assimilation and success of today’s descendants can derail transition because, although simplistic, some will say success means the atrocities of the past cannot have been severe or detrimental.

Commissions have become the undisputed mechanism to deliver on truth-telling here, even though many in Australia’s dialogues saw them as timewasters – kicking cans down the road on substantive reform while we tell our stories. And it is not only royal commissions and commissions of inquiry that rarely deliver on change. Truth commissions globally have almost never delivered on the justice claims that victims call ‘repair’. On the other hand, although it’s the subject of much comment and criticism, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a pioneer in this space in the sense that it was created through a judicially supervised and negotiated agreement – not a statute or an executive power. This novel establishment phase allows the commission to be created from discussions between the state and First Nations peoples so that the issues relating to the bias and legal restrictions of commissions of inquiry can be navigated. In any truth exercise involving First Nations peoples and the state, there are two parties; therefore, having the two parties conceive of an agreement that is neither statute nor executive power allows the aggrieved party to have greater input, leading to greater legitimacy and buy-in from victim-survivors.

Even so, while all commissions require First Nations peoples to perform stories to the point of exhaustion with lofty rhetoric and promises of liberation and emancipation and healing and justice, such promises never eventuate. Athabascan scholar Dian Million argues that trauma and healing are now co-opted by the state and detached from broader Indigenous political goals for self-determination. Million states that ‘these commissions are a product of our age, an age of human rights, global violence, mass media and neoliberalism’.

Million is correct. Australia’s reconciliation movement – or at least its appetite for truth and justice – went into abeyance in the early 2000s when then-Prime Minister John Howard rejected the recommendations of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and pushed back on the fundamental infrastructure required to address the country’s ‘unfinished business’, such as constitutional recognition and treaty. Howard contrived a binary between practical reconciliation (employment and participation in the labour market) and symbolic reconciliation (constitutional change, structural reform, etc.). This meant that any discussion about structural change or right to a voice was disregarded by the Howard government and pilloried as ‘symbolism’ ineffective for change on the ground. Structural change and rights were off the agenda until 2010, when Prime Minister Gillard took office. James Cockayne, professor of global politics and anti-slavery, argued in the face of this:

They seek to achieve reconciliation by providing ‘practical’ measures such as improved service provision. This ‘Reconciliation’ approach denies the utility of practising reconciliation by treating indigenes as a distinct group with specific rights distinct from other Australians; to accept such distinct rights, to accept this difference, is perceived as tantamount to accepting the division of Australian ‘unity’. Practical Reconciliation becomes a way of denying indigenous difference and its social and legal consequences.

Cockayne’s framing of reconciliation during the Howard era has resonance with the policy climate today. There is a risk in framing of truth projects in a reconciliation that is about the pursuit of ‘reconciliation’ as opposed to the justice claims that First Nations peoples say must be repair. I agree with American scholars Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson when they say that truth commissions can ‘sacrifice the pursuit of justice as usually understood for the sake of promoting some other social purpose such as reconciliation…’ This concern was reflected in the First Nations dialogue deliberations and in the Uluru Statement’s agreed sequence of reforms where truth follows structural reform. Gutmann and Thompson allude to a concern I have about truth commissions in Australia: if they are based on the weak reconciliation approach popular in Australia, then they will involve everything but the pursuit of justice – despite every best intention.

Ultimately, truth-telling must come from local communities. The idea of the Makarrata Commission mentioned in the Uluru Statement is that, if established, First Nations and communities or regions can choose when to lock into the commission for resources and when to share their stories with the world. This work might be undertaken in conjunction with local councils, local history societies or other local community groups. Indeed, as historian Penelope Edmonds has explained, locality is key because so many individuals and communities are wary of attempts at reconciliation led by the government, viewing previous attempts as ‘state-based and top-down social program[s]’ that can be ‘repressive’. The Makarrata Commission, if established, should not step into this space of local truth-telling but should support it. Every single First Nation should choose how truth-telling should occur. They are entitled to properly resourced dialogues so that their development is ground-up. They are entitled to decide whether to pool their resources and work with other First Nations locally or regionally. And they should be able to access support, including resources for stories to be collated, archived and, where appropriate, made public with relevant permissions. This would create a record of history: a unified understanding of the contested nature and experience of Australia’s history. It would create, as historian Mark McKenna says, a nationwide footprint of the violence of our history.

The Uluru Statement invokes the word ‘Makarrata’, a Yolngu word taken from a dispute resolution ceremony from the Gumatj clan located around Yirrkala in the Northern Territory: it means ‘coming together after a struggle’. There is a significance in asking for a Makarrata Commission to supervise truth-telling because Makarrata itself is a process. The participants in the Regional Dialogues that preceded the Uluru Convention emphasised that the truth was not about them as victims, survivors or as resistance fighters but about all Australians – now and, through ongoing educational programs, in the future. The idea of Makarrata, of coming together after a struggle, was offered as part of a sequenced proposal to the Australian people to create a different future. The idea of an independent commission to oversee the negotiation of a range of agreements and truth-telling process demonstrates the shared and various nature of this truth-telling. It is not for First Nations peoples only; it is not owned by any particular group. It is for all Australians as we come together after the many – and often violent and tragic – struggles of our past.

RECONCILIATION HAS NOT progressed because we fail to hear what First Nations peoples say is repair, and this ‘ethical loneliness’ exacerbates poor health and dislocation from the wider population and public institutions. The failure to listen to the First Nations dialogues’ nuanced and finely granular vision of ‘truth-telling’ is one demonstration of this: the continual ignoring of community voices. It also demonstrates the urgent need for the Voice. The proclivity of those who should know better to single out truth-telling from substantive reform demonstrates why reconciliation here is stalling. It needs a roadmap. The Uluru Statement from the Heart provides an uncluttered, sequenced pathway forward. But it does require dispensing with the popular but false notion that Australians do not know who we are. It is not true that ‘we weren’t told’. This narrative has been driven by historians as well as anthropologists such as William Stanner and his theory of the ‘cult of disremembering’, which has been reduced to glib catchphrases parroted by a national elite who prove the point that empathy is a block to law reform. We do not need empathy – we need action.

The idea of Voice, Treaty and Truth is not to create an à la carte menu where truth can be singled out while hard asks – such as an enshrined Voice to Parliament – are avoided entirely. In its National Reconciliation Week earlier this year, Reconciliation Australia chose as its theme ‘Be Brave. Make Change.’ This ask was a significant turning point for Reconciliation Australia, calling upon its many followers to be braver about what it takes to achieve change in this nation, to take braver actions than reconciliation action plans. And yes, this may mean corporates or universities supporting something positive for the nation that may antagonise a prime minister or the government or the bureaucracy.

There is nothing braver in this nation than asking the Australian people to vote ‘Yes’ at a referendum. They have said ‘No’ to changing the Constitution thirty-six out of forty-four times – that’s only eight nods. And politicians quake in their boots when they hear that word, referendum.

The reality is that our old people said the Australian people were ready during the Uluru dialogues. It was the old people who requested the Uluru Statement be issued to the Australian people as an invitation. It was the old people who said simply: we did it in 1967; we can do it again.

Who said, be brave. Make change.

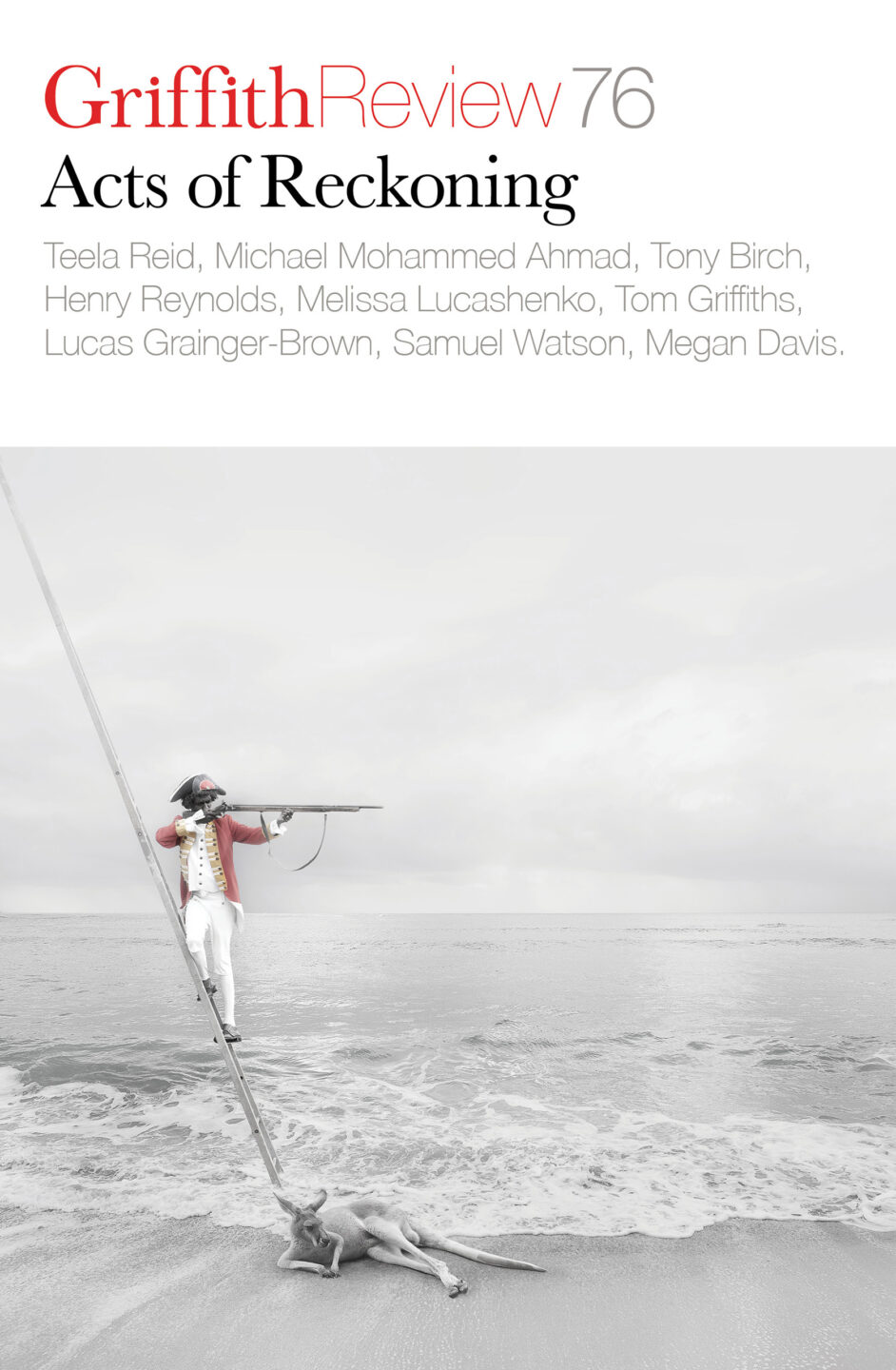

Image credit: Jason Ham from Unsplash

Share article

More from author

The long road to Uluru

EssayUluru is a game changer. The response of ordinary Australians to the Statement has been overwhelming…a rallying call to the Australian people to “walk with us in a movement…for a better future".

More from this edition

the sweet lie

Poetrymy ancestors peer towards dry land from the deck of a ship; or are they like swine, packed into the hold to see the sun only...

Radical hope in the face of dehumanisation

In ConversationOur Elders are the epitome of these thousands of generations of existence and survival in this place, and if we’re thinking about the future of the world and our survival, we need to be learning from these people. They hold the most knowledge, the most intimate knowledge of not just surviving but of thriving and maintaining generosity in the face of all the challenges.

Q/A

PoetryU like America? No U like China? No U like Australia? Sort of U like what about Australia? A small country pretending to be bitter than it is, I mean bigger U dislike what about...