Seeing the bigger picture

Why illustrated children’s books are essential reading at any age

Featured in

PICTURE BOOKS ARE not just for children. When we’re young, they inspire and facilitate our literacy journey, teaching us how words work and what we might expect from a narrative. They’re among our first social mirrors. They’re enticing windows through which we begin to discover diverse and imaginary spaces. And they stay with us. Most adults who grew up reading can name at least one beloved picture book from their childhood.

If a literary format can achieve all this – spark a lifelong love of reading, underpin social and emotional identity formation, conjure stories that linger in hearts and minds for life – then logically, the contents must be constructed with an outstanding blend of science and sophistication. Yet, as adults, we tend to think of picture books as simplistic stories from which readers should eventually move on.

In leaving picture books behind as soon as we are ‘old enough’ to read longer works, we deny ourselves the pleasure and practical benefits of the art form. With so much more to teach us than early literacy skills, picture books should be essential reading at every age.

ONE OF THE key skills required to write an excellent picture book is being able to capture big ideas in few words. The current industry norm is 500 words maximum for a commercial picture book, without compromising on strong character development, a compelling narrative or a satisfying conclusion. There should be no wasted words. More and more of our daily interactions with text, such as social media and online forms, require adherence to restricted character numbers. Why not learn from the best?

Effective storytelling in short word limits is not just about running the red pen through extraneous adjectives, either. It demands creative problem-solving, like seeking out useful synonyms, rephrasing and reconsidering the core message. The more reading one does of well-structured short fiction, the more naturally one can recall the solutions others have deployed.

Picture books also have a way of getting straight to the heart of a tale – in part because there is no time for a lengthy backstory. Most picture books contain one narrative catalyst in the form of a problem to be solved or obstacle to be overcome by the protagonist. Little Red Riding Hood must get safely to Grandma’s house. The Very Hungry Caterpillar must find food to eat each day. Within the pages of a book, the character’s heart and mind are directed towards one goal, which is as meaningful to them as any survival imperative.

Understanding someone’s goals and motivations in simple terms – especially if they’re radically different from your own – goes a long way towards encouraging empathy. In psychology, this is known as a theory of mind: the capacity to comprehend that other people hold differing beliefs and desires from one’s own. This is an important lesson for children to learn, and often explicitly demonstrated by a character’s journey of change in a picture book. But adults can also benefit from recognising other people’s deeply held values by exploring them in texts where the stakes are low. Many of the texts we choose to read as adults are complicated and nuanced – picture books can make the empathic experience of reading much clearer.

Lisa Cron in Story Genius, an analysis of writing and brain science, references functional MRI studies about reading and empathy. ‘When we’re reading a story,’ she posits, ‘our brain activity isn’t that of an observer, but of a participant.’ When absorbed in a book, you experience what is happening to a protagonist along the ‘same neural pathways as you would if it were actually happening to you’. Studies have shown that, consequently, regular reading of diverse texts reduces prejudice and positively impacts our tendency towards helping behaviours. This can be especially true if picture books, with their strong moral themes, are included in our literary diets.

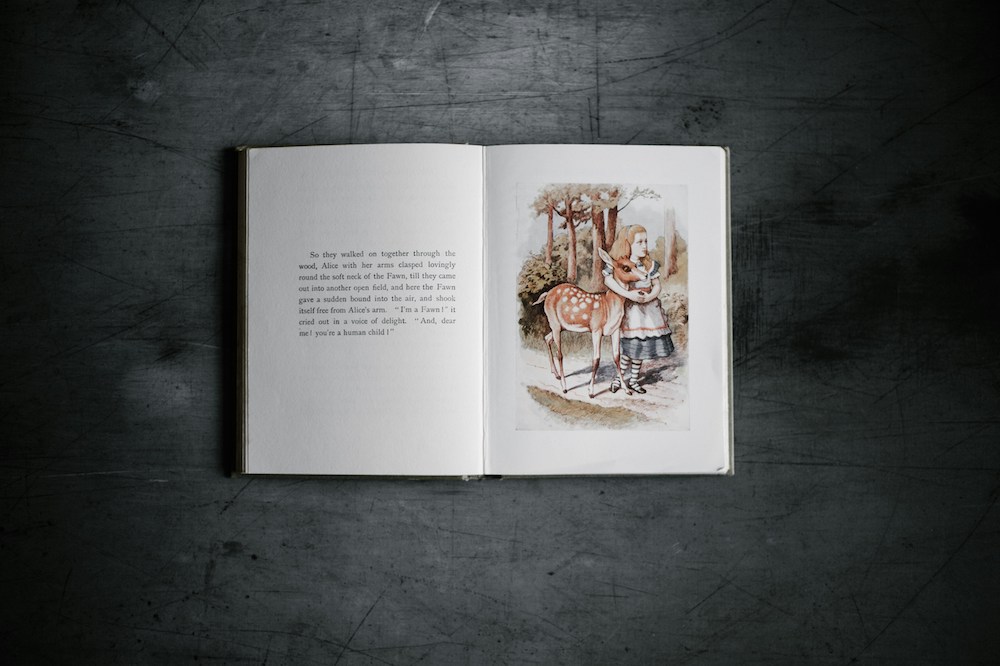

THE ILLUSTRATIONS IN a high-quality picture book are constructed with the same melange of creativity, pedagogy and compressed storytelling as the words. Far from being merely decorative or attention-grabbing, they foster visual literacy. Each double-page spread is constructed to evoke a mood. The reader is manipulated by artistic devices such as the use of a specific colour palette or the careful placement of objects within white space. Like a frame of a film or a gallery painting, the pages of a picture book can be read without words and interpreted in different ways by different viewers. When read with the words, the illustrations expand the story, often providing additional information or even a counter-narrative in more playful examples.

Visual attentiveness is a survival skill. We process thousands of visual indicators per second to safely navigate traffic, for example, even though we’re not conscious of the process. We interact with all visual stimuli in similar ways, including the images and videos that increasingly dominate communication. In the social media space, we’ve witnessed a shift in the ubiquity of text-driven Twitter/X towards highly visual TikTok and Instagram reels. With each scroll, we have milliseconds to decide what is interesting or relevant to us and what message we should take from the visual presentation. Generative AI will further blur the line around what is ‘real’ in any given image. The complexity of visual storytelling in picture books is far beyond that commonly found in our social media feeds. Taking time to appreciate the explicit and subtle layers of messaging crafted for each spread helps refine our visual lexicon. These skills are invaluable when it comes to spotting biases in news footage or tropes in advertising campaigns.

‘WHEN YOU READ children’s books, you are given the space to read again as a child: to find your way back, back to the time when new discoveries came daily and when the world was colossal,’ says author and academic Katherine Rundell in Why You Should Read Children’s Books, Even Though You Are So Old and Wise. It can be genuinely difficult to imagine a space in which only one thing requires your attention. As adults we have the world’s information at our fingertips (online, at least) but we struggle to sift, select and retain it, particularly when juggling our so-called work/life balance.

It’s no surprise that ‘mindfulness’ has become a buzzword, broadly adapted and (mis)interpreted to mean almost any kind of me time. Most of us need to stop, sit, breathe and think (or not think!) more often than we actually do. A picture book is the perfect conduit. Whereas silencing the mind can be challenging, putting your focus on one short, beautiful text can be meditative. Perhaps this is why Australia Reads research suggests a 20 per cent reduction in mortality for those who read books for thirty minutes a day. Slow down, read books, and potentially live longer!

THE NOTION THAT reading children’s books as an adult is somehow a step backwards erroneously suggests that our lifelong reading journey is entirely linear. If you are lucky enough to enjoy a smorgasbord of entertainments, you are already picking and choosing from shorter or longer, lighter or heavier texts at all times. If you’re deliberately avoiding picture books for no other reason than the assumption they are too childish, you are missing essential intellectual micronutrients.

To again cite Katherine Rundell, if you could only read in one direction of increasing complexity ‘you’d be left ultimately with nothing but Finnegans Wake and the complete works of the French deconstructionist theorist Jacques Derrida to cheer your deathbed’. As individuals, we each have our own tastes and interests, of course. But omitting a whole book format for fear of stalling in the race to an imaginary finish line is unnecessary.

Not all picture books are created equal, however. Like any book format, there are accomplished beauties and there are flashy stocking-stuffers. It’s understandable that some adult readers are deterred from picture books by limited exposure to high-quality examples. But there are several ways for adult readers to find the good gear.

Like Hollywood, children’s books have their own awards season. Seek out those books with a stamp of approval from the Children’s Book Council of Australia or Speech Pathology Australia. Visit your library or local independent bookstore and ask the experts for their suggestions. Book advocacy bodies also compile lists of recommendations. Try the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature’s Picture Books for Older Readers database as a rich exemplar.

Finally, with all this said, if there is one reward to balance the rigours and responsibilities that occupy much of ‘adulthood’, it’s surely the freedom to read whatever the heck you like. Justify it as professional development if that helps, but you could also choose to read picture books just for fun. Imagine that.

Image credit: Annie Spratt from Unsplash

Share article

About the author

Lara Cain Gray

Lara Cain Gray is a writer and librarian from Meanjin/Brisbane. She is the children’s book specialist at non-profit publisher Library for All. Her next...