Featured in

THIS IS A story about my father, Ron Hurley, the first Aboriginal artist to graduate from the Queensland College of Art. With the upcoming anniversaries of his birthday (19 October 1946) and passing (3 November 2002), I wanted to remember him and to reflect on the retrospective exhibition of his work, Nurreegoo, that was held at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art more than ten years ago. It’s a story about words as well as artwork. A story about family and its broadest meanings. A story about the complexity of language and the different ways of naming in the world.

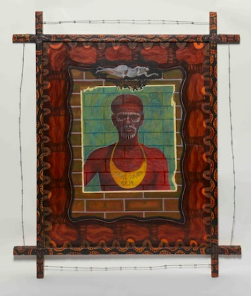

The importance of these things is observed in works that were exhibited in the retrospective, including My Grandmother’s Story (1994). In this painting, framed by barbed wire and sticks, the collage contains contemporary photographic imagery as well as traditional images of the Gooreng Gooreng people. It tells the story of Ron’s grandmother, escaping a large search party after being taken from her parents to be sent to work as a domestic. In Dot and Hector with Owl Totem (1991), a multimedia diptych is a storytelling tribute to my father’s family Elders.

My Grandmother’s Story, 1994

Representations of ancestry were prominent in my father’s work and largely adhered to the protocol of following a matrilineal line – that of his mother’s, the Gooreng Gooreng people. This nation is situated generally north to south from the Gladstone to Bundaberg districts and west to the southern areas of Cania Gorge.

When I was looking for a title for the retrospective exhibition, and in adherence to cultural protocol, I sought permission and input from my Uncles, and my father’s first cousins, respected Gooreng Gooreng Elders Colin and Mervyn Johnson. I arrived at the word nurreegoo, a Gooreng Gooreng word that has more than one definition. Its literal meanings are corroboree, dance, entertainment. As it was explained to me, there is no exact word for artist in Gooreng Gooreng language: nurreegoo is the closest.

Although they do hold words with singular meanings, Aboriginal languages also encompass words that are practical, words that address overall understandings of states of being and circumstances, of events, moments or items. These words are all highly contextual and have different meanings depending on the situation. A long time ago, I listened to a recording of an anthropologist’s conversation about Aboriginal language. The anthropologist asked an Aboriginal man the word for tree. He provided a single-word answer. The anthropologist’s questions continued, insisting on specific words for parts of the tree – the branches, the leaves. The man provided the same word. Suddenly, I heard the Aboriginal man, frustrated, get up and walk away. His amusing response – ‘Go away. Go away now’ – faded into the background. What had not been understood? Maybe that there was no specific word for branch or leaf. Or that the word for branch is the same word used for arm or for the extension of a river. Nevertheless, it seemed that only one word was required to describe and identify that tree.

THE DEFINITIONS OF the word nurreegoo – corroboree, dance, entertainment – hold culturally important understandings of their own: related to one another, they combine to embody one element of understanding in terms of my father’s work. They merge a post-classic, modern-day expression of traditional names.

I see the corroboree of his work in the gathering of traditional knowledge and information and its artistic presentation. This knowledge, this information, was represented in all of his creations to tell the story of his people – creations that speak to their history and truth. This is a narrative Australia continues to omit from its national story and an education Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to embed in their work and lives. My father’s recurring use of Nyarla – ‘the Owl’ totem image – throughout his work is a constant reminder and stamp of Gooreng Gooreng sovereignty.

Miriam Vale Jimmy and Owl Totem, 1982

I see the dance in his effortless transition from one medium to another – not only the use of multimedia within his creations but the diversity of the many media he mastered. Moving easily between them all, he was inspired by the tradition of visual art painting but grounded too by the earthly working of clay into pottery and ceramics. He brought life to people and story through his depictions in print and drawings, also creating monuments of Aboriginal heritage and culture through sculpture and public art. The results were interactive displays of concepts, ideas and emotions, with a choreography of materials that reflect past and present experiences of Aboriginal peoples’ circumstances. As his art pieces journeyed from start to finish, they were also in effect their own dance or corroboree, each slowly revealing a story.

Urban Gurang #1, 1994

And I see entertainment as his raison d’etre, his intent, meaning and purpose as an artist. I see in this his passion and dedication to both his own work and the field of art. Woven through his work are themes of reminiscence, humour and the political, both subtle and overt. These shine a spotlight on his peoples’ struggles, celebrating their resilience and achievements, holding them up as role models, esteemed in their own right. My father loved to entertain and was entertained by life. From his early caricatures and cartoons through to his later and larger pivotal contemporary pieces, Ron Hurley’s work engages its viewers, artistically opposing Western conceptions, Western views and Western ways of knowing. His works entertains its audiences via the mental stimulation of thought-provoking material, subjects and presentations.

Portrait of George Everett Johnson, 1989

MORE THAN 250 languages, including hundreds of dialects, define Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies. Identifying ourselves culturally through language names and totems provides security, belonging and a sense of wellbeing. Our responsibilities for maintaining relationships with one another and with our land are delineated by this. And identification through personalised totems – usually animals – carries the extended obligations of protection and the passing on of knowledge for that totem. If names identify our family lineage, then language is fundamental to the understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and our connection to spirituality.

Non-Indigenous definitions of the word artist often address literal descriptions of people who use skill and imagination to create and produce art through various media; these often provide a task-oriented description of differing contexts. Descriptions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists also hold varying elements surrounding issues of identity, connection to land and culture, tradition and customs, authenticity, spirituality and protocols.

There are many Gooreng Gooreng language words I can use to describe my father’s work, including thoolbar (courage), wooli (loud), dellgair (strong) and goolarn (beautiful). But the title of his retrospective exhibition, Nurreegoo, is not just the merged description of an artist; it is word that speaks to a way of being, a more complete story about what he did, how he created work and why.

Language translation involves more than simply replacing one word with another, one meaning with another. Language is a powerful tool of expression that inspires and influences the way people act and interact.

The name Nurreegoo was awarded to my father after his passing. As a proud Gooreng Gooreng man, he would have considered this name an honour.

Share article

About the author

Angelina Hurley

Angelina Hurley is an Aboriginal woman from Brisbane of Gooreng Gooreng, Mununjali, Birriah and Gamilaraay heritage. A writer and Fulbright Scholar, she is undertaking...