Featured in

MAYBE YOU’VE SEEN it: a viral Amazon book review in which the reader describes Pride and Prejudice as ‘just a bunch of people going to each other’s houses’. It’s funny, in one sense, because it’s true. But most of us get the joke when a Twitter user calls it their ‘favourite piece of literary criticism of all time’. Is this, in fact, literary criticism? Can we even call it a book review?

Since Elizabeth Hardwick famously lamented the ‘decline of book reviewing’ more than sixty years ago, countless articles have appeared in her wake, declaring the review either moribund or already dead. Some of these concerns relate to quantity. Most are about quality. Whether they’re lambasting the internet-fuelled democratisation of book reviewing, the disintegration of analysis into fandom or takedown, or an insular (even incestuous) publishing ecosystem in which the reviewers are simultaneously the reviewed and therefore disingenuously lavish in their praise, the so-called critics of the critics remain convinced that book reviews just kind of suck.

But if writing and reading about books means we’re ‘perpetually stressed and disappointed with book reviewing’, I can’t help but wonder if this recurrent hand-wringing demands more than to be defended or disputed on the grounds of accuracy or defensibility alone. Are book reviews ‘good’ or ‘bad’? Is the ‘soft vs snark’ binary real? These are, perhaps, interesting and important questions to ponder. But there’s a futility in them, too, a tendency for the frequent paroxysms of ‘decline polemics’ to merely perpetuate themselves, while calls to ‘do better’ are palliative at best and unwittingly caustic at worst.

Why? Because these reprovals obscure the nature of reading itself.

ASK GOOGLE WHAT book reviews are for and the top results will confidently declare a focus on describing and evaluating the ‘literary merit’ of a given book; ask anyone else and they might characterise reviews as a form of critical or intellectual sociability, mechanisms through which writers and readers enter into dialogue, indispensable cogs in the marketing machine, a way to filter new titles through to an overwhelmed reading public. What becomes clear, however, the closer you look, is that books occupy a difficult position as both art and commodity. It’s possible that book reviews, attempting to straddle both worlds, can never actually win.

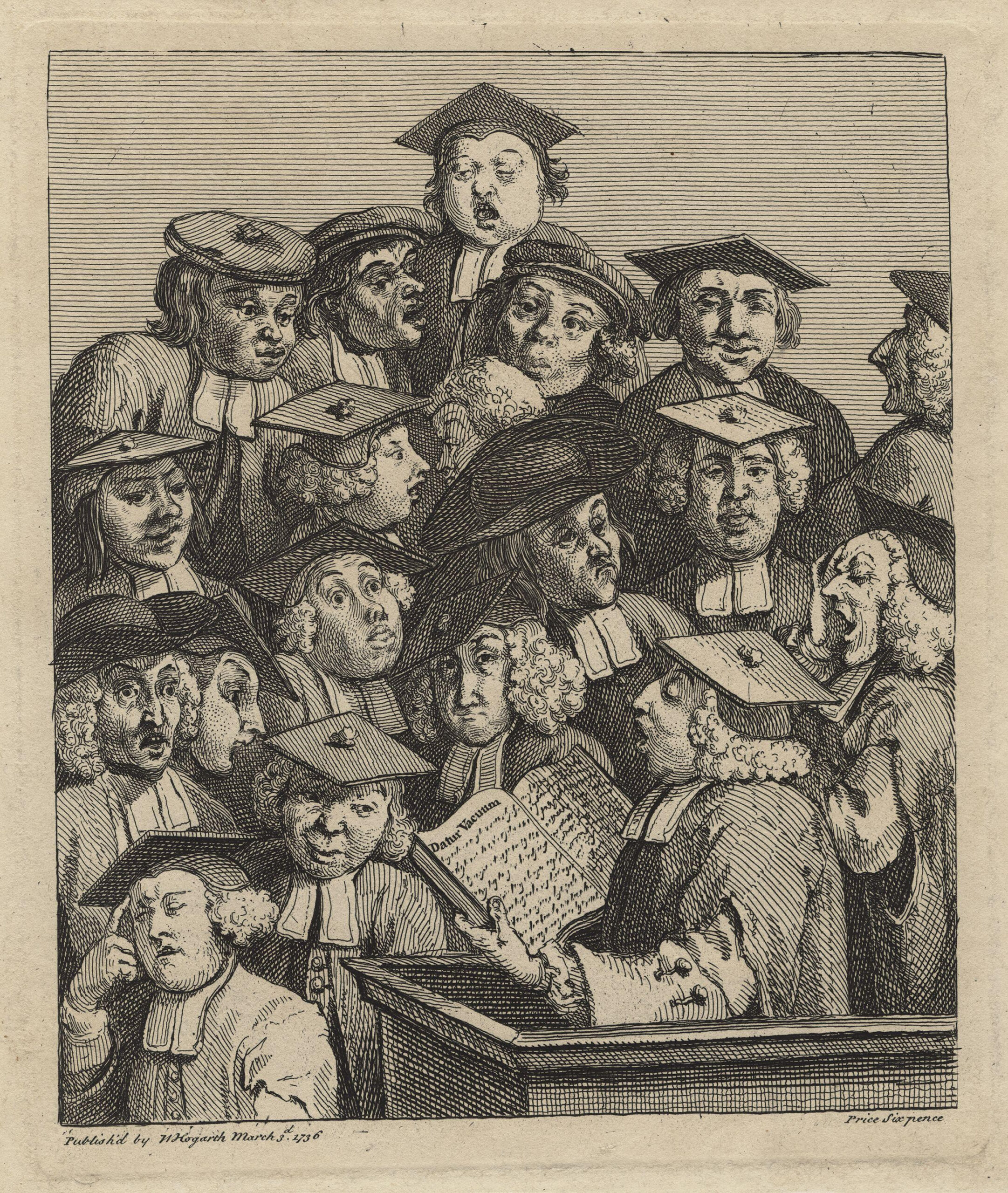

When we analyse a text, we recognise an artefact that’s not cleanly quantifiable; we use methods that are not strictly formalised, and the results cannot be objectively verified. But by professionalising literary criticism – asserting the status of trained critics – we’ve inadvertently calcified our expectations around what it means to respond properly to a given text: a hangover that demands we take the act of reading as axiomatic or self-evident, one in which those readings are definitive, meanings and values sedimented in layers only experts can be trusted to excavate.

So, when a commentator famously takes aim at Australian critics by sneering at what a ‘wide divergence of opinion’ should tell us about ‘people’s motives for reviewing’, he prolongs a pervasive fear of ‘interpretive anarchy’ still rooted in dated ideas not only about how people should read but about how people actually and always read.

Ah.

I don’t like this, and it’s not just because such a perspective doubles down on what most of these admonishments share: that there’s a right and wrong way to read and, by extension, right and wrong readers to do it. It’s the idea that in a supposedly sophisticated or rigorous reading, we can somehow circumvent our very human idiosyncrasies, that divergent readings, situated in the unique circumstances of our lives, are somehow repellent because they are refracted through us – active agents who must work to make a text meaningful.

It’s mysterious to me because nobody would argue that reading can happen without someone who reads. But when we consider the results of this activity (a reader making sense of a text and its qualities, assessing its various merits and shortcomings), this is exactly what sound criticism or a ‘good’ review still supposedly demands. We, the inevitably imperfect human reader, are meant to just disappear, to jump out of frame, removing all traces of what we’ve done or the context in which we did it – criticism as the perfect crime.

THE PROBLEM WITH these lingering assumptions, aside from the seam of snobbery deeply embedded in their perpetuation, is how they misrepresent reading as altogether neat and tidier than it can ever hope to be.

Authors themselves typically demand less. William Golding, for example, writing about the popular reception of Lord of the Flies, eventually concluded that if an interpretation is yours, ‘then that’s the right one’ because ‘what’s in a book is not what an author thought [they] put into it, it’s what the reader gets out of it’. In one passing comment, he summarises the basic premise of contemporary reader-response theories: that books don’t just happen to people, as Louise Rosenblatt has put it, but that people also happen to books. Reader response is preoccupied primarily with exactly that – how we happen to books – and it’s here that the book review, as affected and learnt as any other mode of performance, is destined to languish if it cannot see itself as such.

Do I mean to say that PaigeTurner84 on Goodreads should hold as much sway as Frank Kermode in The New York Review of Books? Well, kind of. There’s plenty to be learnt from non-specialist readers, who bring their own forms of expertise to the table. But that’s not what I’m getting at. What I really mean is that while not every response may constitute a review, every review is necessarily a response, and by setting aside the expectation that we should all, in fact, read the same way – liberated from the bonds of idiosyncratic experience, the various ways we’ve been socialised or institutionalised into reading, the competing demands associated with the task of eviscerating our responses – we’re no less beholden to doing good, honest work, but we’re open about the fact that we’re operating on a text, making it do something.

When Anthony Burgess, not only a writer but also an esteemed literary critic, talks about the way texts ‘glitter’ with the ‘impurities’ we call meaning, I think he’s getting closer to what a book review should do. What else is criticism, after all, but a way to take stock of these residues, the things that aren’t meanings but the things we call meanings – because we’ve made them so? Put another way, if interpretation remains, in the words of Stanley Fish, the only game in town, surely it’s the dirty work that makes things shine. And by rearticulating the rules of the game, by relieving us of the impulse to defend our readings as authoritative, it alleviates the sting of a bad review just as it tempers the sickly euphoria of ‘excessive praise’.

‘How interesting,’ we might learn to say, ‘that you were able to respond that way.’

Share article

More from author

Mustard seed

There are others like me, those who have, in faintly euphemistic terms, left the church, what we might otherwise call the spiritually unmoored, though we’ve invented specific words for them: lapsed – adjective, mildly noncommittal, perhaps only temporary; apostate – noun, sharper, less impassive. But whatever you call us, no matter the nomenclature, we’re now foreigners, I believe, in one place or another, still too much of this to be that, betrayed by something like a subtle accent, a vowel bent out of shape, if you watch or listen for it closely enough.