Radical hope in the face of dehumanisation

Creating a collective future

Featured in

- Published 20220428

- ISBN: 978-1-922212-71-9

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

First Nations peoples in settler-colonial Australia know what it is to be dehumanised, to exist in systems and structures that criminalise and oppress us and our lands and cultures. Curious about the ways forward in a reality that can at times feel deeply debilitating, Kirli Saunders sought the wisdom of two First Nations facilitators from the company Shifting Ground who work with organisations and individuals to foster decolonising practices to pave the path towards a radically hopeful future. With respect and acknowledgement, this conversation took place digitally across unceded Yawuru lands, Larrakia Country and Dharawal lands.

KIRLI SAUNDERS: I’ve been reading both of your work as I create my poetry collection, and I’m drawn to the intersection of abolition and decolonisation: can we start with these concepts?

GENEVIEVE GRIEVES: Eve Tuck, the Unangaxˆ Indigenous studies and education scholar, and K Wayne Yang, who works in Indigenous organisation and critical pedagogy, describe it as ‘the repatriation of Indigenous land and life’. So decolonisation is a place we’re not necessarily going to get to in the Australian context unless you’re giving back all the land and giving us back our humanity. Colonisation is powerful: it’s everywhere. We are completely immersed in it.

We have so much work to do as Indigenous people to decolonise ourselves because we have been brought up in a Western society, in a Western education system: we come into contact with a Western legal system that’s just all-pervasive.

I work with Lilly as a co-founder of Shifting Ground to deliver education that transforms people and organisations across different sectors through the lens of decolonisation, racial literacy and cultural safety. It’s been so useful to name these concepts with individuals, organisations and community and to strengthen the opportunities for conversation and collaboration between us as Indigenous people but also with our allies. And that’s partly why I’m interested in decolonisation and why I see value in the concept and the language around it. Because it is shared labour; it’s not our work alone. It has to be everybody’s work, everyone in Australia: it’s all of our work to dismantle it. That is a really powerful way forward – a way to work together meaningfully, where people are assisting us to break down these systems of injustice.

LILLY BROWN: For me, Gen’s thoughts around decolonisation as repatriation of life sit intimately with and work to counter the way that First Nations peoples have actually been so dehumanised. The current white psychosis that informs the realities of many Australians is contingent upon our dehumanisation…when I’m thinking about actually repatriating life, I’m thinking about how we humanise people.

And for us, we do that every day. I’m always thinking about being a mother and what it means to consciously have positive representations that depict our complex humanity, making those easily accessible for my daughter – because I know when she steps out the door, the whole world is telling her that she’s not good enough.

So, I love the idea of creating spaces, creating futures where we as a people not only deeply know and value our humanity but where that is valued, more broadly, in the places and societies within which we live and move through.

KS: Lilly, a significant part of your research has been around this idea of shifting our punitive system and the criminalised nature of First Nations peoples – and especially kids – in Australia. How does this feed the decolonial frameworks and abolition that we’re yarning about today?

LB: We live in a country where 500 people have died since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. We have the lowest age of criminal responsibility. We’re dehumanised to the point where killing our children and locking us up – warehousing us in prisons – is perceived to be okay. We have the highest rate of youth suicide in the world. And many of the young people dying have had experiences that led them to feel like their lives were not valued… Where I am currently located, in the Kimberley region of northern Western Australia, nine out of ten of our young people who have taken their own lives were living below the poverty line; those kids being locked up, in most instances, are put away for minor crimes like stealing. In the Broome town where I live, the stolen cars are attributed more worth by non-Indigenous townspeople than the young people feeling disillusioned enough to steal them. Unbelievable amounts of public funds are spent on sending police up from Perth to deal with the ‘youth problem’ and find them housing when First Nations women and the mothers of these ‘problem youth’ – who are also children – cannot access affordable housing.

There are so many ways in which dehumanisation continues to function in the systems that regulate the society we live in. And those things need to change.

So when we’re talking about decolonisation and repatriation of life, we must be talking about dismantling those systems. When we’re talking about the future, we’re talking about our children and young people. And while our children and young people are some of the most criminalised people on the planet, we are living in a colonial present. It’s ongoing, and so the process of decolonisation and abolition in parallel to that must be ongoing also.

GG: I’m thinking about what Lilly is saying and feeling that as well. I’ve had family members end up in that system because of poverty – but I also think of the number of young people in detention with FASD [Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder] or other disabilities, especially in the Northern Territory. I have a brother with intellectual disability; if he didn’t have us, he could easily have been caught up in that system.

I also think about the destructiveness of colonisation and how that destructiveness continues through law and policy. I’m feeling it living in the Northern Territory because 100 per cent of the juvenile detention population on most days is Aboriginal.

We had a Royal Commission into what happened with Don Dale [Youth Detention Centre], and Don Dale is still open…and after the Royal Commission, they’re actually making it easier to lock up kids, you know? This system is so entirely broken.

I’ve worked a lot in prisons, and the men and women in those prisons just don’t deserve to be there. Most of them have been institutionalised and have come from the children’s homes: they sort of can’t get out. They’re just so neglected and ignored by those in our society who hold any kind of power and access to resources. And once you’re criminalised and framed in that way, it’s hard to get out of a system that really preys on vulnerable people.

KS: I feel that grief and carry it with me too, and I feel grateful to be with you both in this conversation and want to extend to whoever’s reading this, especially our mob, we’re with you in this; we’re holding you in the grief and frustration.

KS: I WAS RECENTLY introduced to this idea of active hope as a counter for climate grief and how we can take collective and radical responsibility to shape our future. With regards to our communities, land and people, what do you think of this idea for our futures?

GG: I absolutely hear you in terms of radical hope: I’ve learnt a lot about this from Elders who hold spaces with grace and teach with love – Elders like Uncle Jim Berg [the Gunditjmara Elder who helped found the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service]. When we worked with police to offer free programs to support cadets (who otherwise wouldn’t receive cultural training), he told me that we have to do this together; we have to work collaboratively. Despite any disengagement from participants, he just held such an open space and open heart to anyone who would work with us – he believes that if you’re with us and you’re helping these young people in prison, if you’re doing this work, then you’re family.

When I’d get frustrated, he’d say to me: one foot in front of the other. You just take small, incremental steps because the big picture can be so overwhelming in terms of how we shift systems of oppression. You have to keep chipping away. I’ve had many moments in my life where I feel like change isn’t happening fast enough. We’ve done all this work; why aren’t things changing? Older, wiser people say to me, be patient, because everything you do has ripple effects. Every little step you take is making much bigger change. It just might take a while to come.

I’ve always held on to that. I think it’s really important to model ourselves in respect of the Elders in our community.

LB: There’s something to be said about watching the way that our people, especially old people, have survived – and not only survived. They’re thriving and they’re building those relationships and they’re changing people’s minds. There are so many instances where they could have completely revoked that generosity and yet, as Elders, they continue to enact that love in a way that blows my mind. It’s so nourishing. There’s so much to fight against. And it’s never-ending.

I see our young people struggle when they see these things happening in the world, and I know that feeling: you feel like you’ve got to throw all of your energy into it – and the burnout from carrying the weight of the world is real.

When we’re talking about decolonisation and abolition, we’re talking about it being a process and an end point. We have to invest in ourselves during that process, create space for nourishment and ensure that we’re also building relationships with one another and with other people of colour. It’s like the constellations of resistance that Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, a Mississauga Nishnaabeg writer and academic, talks about: building those constellations of resistance so we’re held in that way.

And it’s not just about sitting in opposition, because that can take everything: there has to be something left over. If the fight is ever to end there has to be something left over.

Even sitting on this call and knowing that in publishing a piece, it’s going out to the world: people are going to receive it and audiences will read it – we’re creating those communities of practice, those constellations of co-resistance and those relationships. Ensuring as well that we’re taking care of one another throughout the process is important.

KS: I love these constellations of co-resistance! Are there other ways you can see us creating our collective future? What is the role of Black joy here and how do you remain grounded and safe?

GG: Part of the radical hope for me is also doing the work that we do in transforming non-Indigenous people in terms of their understanding and their humanising of us: I get a lot of power and strength and nourishment from that. But it’s not easy to hold spaces; it takes a lot of energy. We’ve worked out ways to hold and support one another through the work we do at Shifting Ground. Lilly is great at setting up the space so that we build relationships and form a shared language to keep everyone safe. We’re very considered in how we engage with people to make change.

I gave up, quite a long time ago, responding to general acts of racism around me. As a young person I’d always engage in the fight. I don’t do it anymore. If someone is going to be hurt then I’ll intervene, but if it’s just some fool espousing racism, I don’t engage. That’s partly how I maintain my energy.

I also think it’s just so important that we build in time for cultural nourishment and our connection to one another. We had First Nations artists together for a weekend in Sydney: possum-skin cloak making, weaving, dancing, singing and yarning about projects. It had me feeling very supported and connected with people who care. I was looking at the photos from that workshop recently and thinking, look at these! Everyone is just in pure joy. We need that, and we don’t have enough of it.

These gatherings have the most beautiful energy. We crave that and connection to one another and to culture.

LB: It’s about refusal in a way. It’s not about justifying the creation of those spaces. It’s about resisting dehumanisation with rising energy. It’s also about actively creating and maintaining spaces, in relation, between two people or between a group of people on Country, wherever that may be; even if it’s in the middle of Sydney. It’s about reconnecting that to those places and as a community.

All the moments over the last decade and a half when I’ve been struggling, being held by a lot of spaces that are Black spaces is what’s brought me out of that. Those spaces are exceptional; they’re beautiful and they’ve never been known by non-Aboriginal people. These are the moments and spaces where we do experience joy.

That could look like presence with Country, with the trees, or it could be connecting with our community in texts, poetry, books, which create space. Not in opposition, but because it’s a way of communicating with one another and reassuring one another that we exist, that we’re here; we’re not just here in opposition. We’re here! We’re thriving! I think about our storytellers and I think about the thousands of generations that go into even the utterance of one word… I think it’s ridiculously beautiful.

We’re lucky to surround ourselves with one another, and the beauty and the joy and the brilliance are not exceptional. But leaders within our community are positioned – particularly by non-Aboriginal people – as an exception…if we’re talking about exceptions then we’re also reinforcing what the rule is. But the rule is that we’re not exceptional.

When I know – we know – every one of us knows in any moment: when we’re holding one of our books, or sitting in relation to each other, sitting in relation to our Country, we know that we are exceptional. We are exceptional in the context of humanity. As a collective, as a people: we are exceptional.

If that’s the baseline, it’s just such a privilege to be who we are. That grounds me a lot: just knowing that. We don’t need to prove anything. My partner, he always says, ‘we don’t need non-Aboriginal people to recognise our sovereignty for our sovereignty to exist’. We know it, and that’s enough.

KS: Thank you – you’re giving words to the things I’ve known for a long time and it’s clarifying to hear them spoken – almost like a sisterly mantra. I love this future we’re imagining too, where we are decolonising systems, creating our own safe Black spaces, connecting with community, culture and Country, and challenging and refusing dehumanisation. What else would you like to weave in?

GG: There are teachers and thinkers who don’t even like to focus on decolonisation because it’s focused on huge power structures, the struggle and dismantling of all of it: it’s focused on the Western paradigm. The notion of Indigenising really encapsulates all that willingness to not focus on that, pushing against it, but building self-determined spaces and our own ways of doing, being and knowing. I think decolonising and Indigenising can happen in tandem. We need to create spaces that challenge Western paradigms, with the warriors fighting and everyone behind supporting them. But we also need to plant the seeds, to create something that nurtures us – and we need to create it together.

I’m so excited about all the innovation happening everywhere – that there’s more and more about people coming to positions of power, both within the system and independent of the system as well. The more power we have, the more we can imagine that self-determined way of working and being.

Things have shifted so much in the last decade – massive movements across Australia and the globe. I can especially see young people being elevated, doing what they want to do in their own way and being so proud of themselves. It is amazing to see.

LB: There have been so many big shifts! One major shift has been the focus on the importance of Indigenous Knowledge, which is often understood to be held by Elders, who are also responsible for carrying that and, as part of the responsibility, to pass it on.

We need to complicate this conversation with non-Aboriginal people, because as long as young people are being locked up in the way that they are, as long as young people (who choose strategically not to engage with education for their own safety) are positioned as non-compliant, as long as at-risk children are all justified for incarceration…we can’t be talking about just the importance of Indigenous Knowledge to fix the problems that non-Aboriginal people have created.

I’m all for this valuing of Indigenous knowledge, but you also need to be valuing the relationship between Elders and young people. Education systems need to evaluate the ways in which we’ve been devalued and dehumanised and then the way in which old people are being undermined and not recognised in their full power. They need to understand that those two things are related.

We can’t use Indigenous knowledge to ensure futures if we’re not understanding and supporting young people to sit in relation to Elders and receive that. That knowledge is theirs.

GG: Yes! There is huge narrative around the value of Indigenous knowledge now – I’ve heard so many stories of people desperate to help and to support their Country, you know, to be healed. But the white blindness just stops these institutions from even being able to hear people properly. So even when they say they’re engaging with Elders, they’re still not listening. They’re desperate for this knowledge because they realise that it’s actually tied up in their survival, but they still can’t really connect to it.

LB: Absolutely. The Indigenous psychiatrist Helen Milroy talks about the idea of white psychosis, that it’s actually unwell. When Gen says that this reality is something that they cannot see, that they try to engage in but cannot hear…they have a problem.

Our Elders are the epitome of these thousands of generations of existence and survival in this place, and if we’re thinking about the future of the world and our survival, we need to be learning from these people. They hold the most knowledge, the most intimate knowledge of not just surviving but of thriving and maintaining generosity in the face of all the challenges.

KS: I can’t wait for that moment when they, our old people, are heard properly and when our kids know deeply that they are not the problem. These conversations are beautiful moments of recognising that a shift that is happening, and I feel so grateful to sit with you both in this yarn, imagining this future. Thank you so much for your time, for your wisdom and for your willingness to share.

20 October 2021

Image credit: Getty Images

Share article

About the author

Kirli Saunders

Kirli Saunders is a Gunai woman, multidisciplinary artist, writer, educator and consultant. Her award-winning books include Bindi, Kindred and The Incredible Freedom Machines, and...

More from this edition

‘The True Hero Stuff’

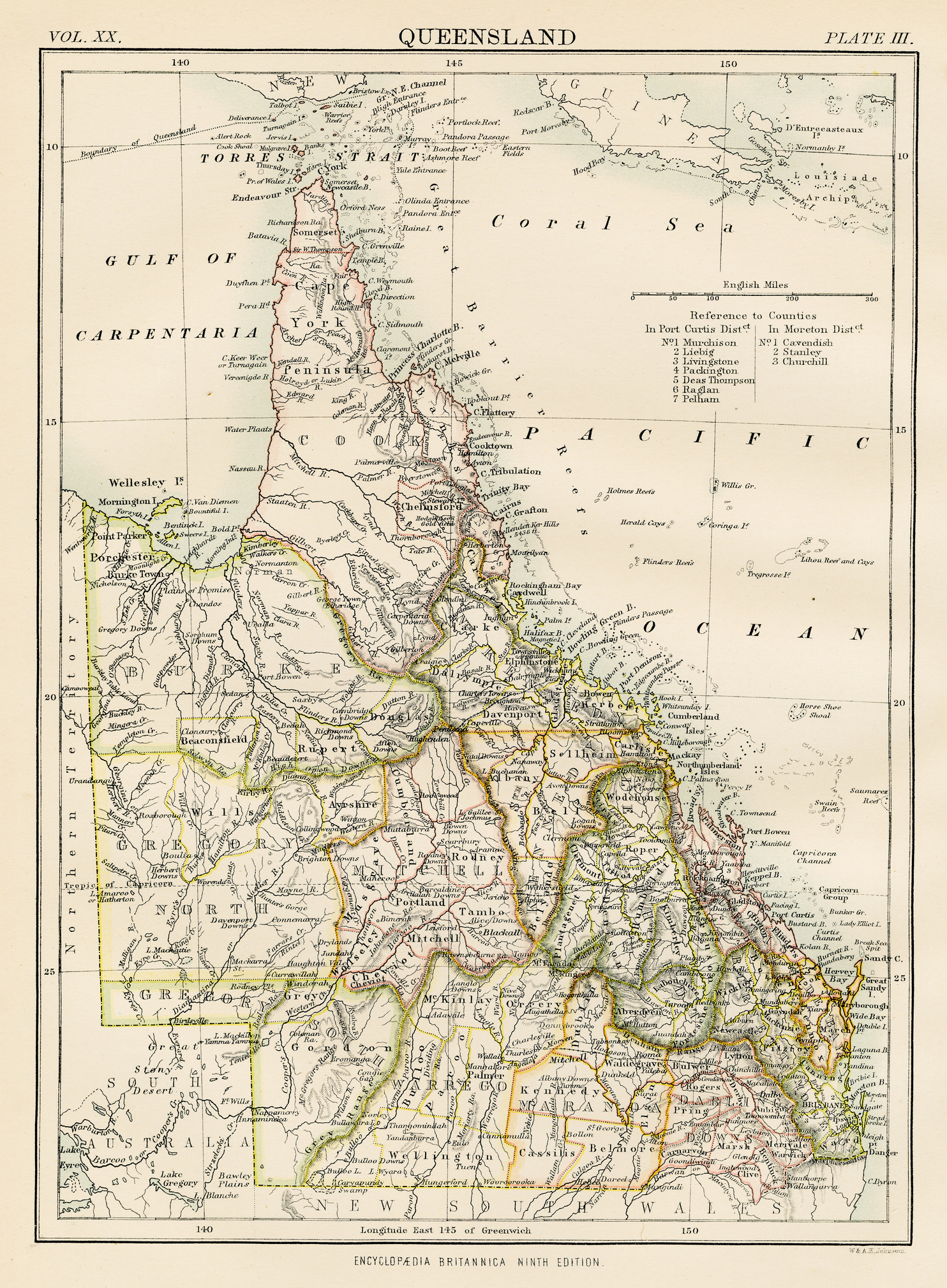

GR OnlineI grew up in a Queensland still so saturated with racist ideology that my own identity was hidden from me until as a teenager I started bringing home questions about our family’s tan skin and curly dark hair. Forty years later I was very well aware that non-First Nations writers usually mine a vast well of ignorance and stereotype when they attempt to bring Aboriginal characters or themes into their work.

Kangaroo Island 1819

PoetryThe fucker’s hanging in the air. The rope’s as black against the light as his black skin, though his skin is bright with sweat where the...

They cannot say their thoughts

(or, If Cohen sang Oodgeroo)

PoetryDance me to the rhythm of a language (I don’t speak) ’Neath sapphire-misted mountains they might kill (ya) Breathe out brokin holy in this land of...