Featured in

Johnny Burnaway (image credit: Gary Warner)

MY UNCLE JOHNNY is buried in an unmarked grave at Hemmant Cemetery in east Brisbane. There is no headstone at which to lay flowers or even a plaque to attend to. The first time my mum, Cathie, visited, she went alone. She tried to locate the plot from the map she’d been handed at the entrance and her hazy memories of Johnny’s funeral three decades before. After a while, she gave up and said a few quiet words to her brother somewhere out there in the field of graves, before shedding tears of frustration and shame on the taxi ride home.

In 2020, on a muggy December day, we retraced her steps, pausing over vacant plots and wondering if this was where Johnny was interred. It struck me as an appropriate symbol for his story. My uncle was an elusive character, remembered as ‘Zap’ by his old schoolmates, ‘John’ by his adult friends and ‘Johnny Burnaway’ to those in the Brisbane punk scene.

Johnny died in July 1988, almost a year and a half before I was born, so although he was family, he is effectively a stranger. Before I began researching his life, I knew almost nothing about him save for his suicide, his drug addiction and his involvement in a couple of bands. He existed in my mind as little more than a punk caricature.

As a child I spent some time with Johnny’s older brother, Michael, before he died suddenly in 2001. Although I was too young to recognise it at the time, this double blow left Mum as the pivot between two sets of brothers. Her dead brothers, Michael and Johnny, had been born seventeen months apart in 1957 and 1958. Her two sons were born twenty-one months apart in 1988 and 1989. My brother Jack, the eldest, was named after Johnny; I was given Michael as a middle name.

Mum blamed music for the turn of Johnny’s and Michael’s lives – or at least the post-punk underground scene that she saw as their gateway to heroin and hopelessness. She set about excising that part of her history from the stories she told us kids. Determined to act as a bulwark between us and the trauma of her past, she did not want us to romanticise Johnny’s death or follow in her brothers’ footsteps. Jack and I were enrolled in team sports and forbidden from learning musical instruments.

But in my final year of high school, Mum discovered she had hepatitis C – an affliction that she is certain came from sharing needles with Johnny, who had died with the disease. Now Mum had to explain to Jack and I that she, too, had experimented with drugs in her twenties. And we both had to get tested in case we had contracted it when we were born. As the nurse took blood from my arm, I joked that I would have made for a good junkie, such was my comfort in receiving the jab. Mum didn’t laugh. Thankfully, neither Jack nor I were positive, and Mum recovered. I cannot say for sure whether that experience opened a new channel of communication, but a few years later, when I was working as a journalist, Mum started talking about Johnny and Michael. ‘Someone should write a story about those two boys,’ she said.

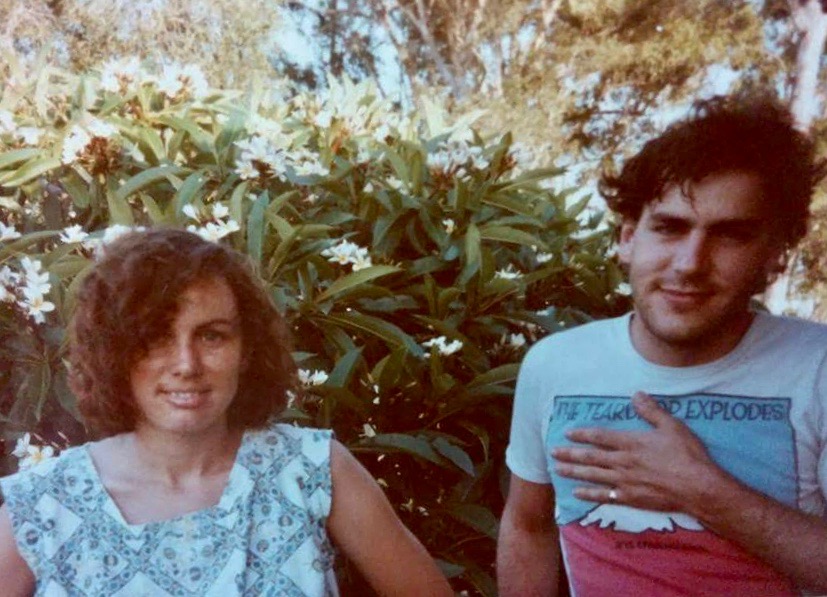

Cathie and Johnny (supplied)

MY FIRST POINT of call was ex-Go-Betweens bassist John Willsteed, now a senior lecturer in the School of Creative Practice at QUT. Willy, as Mum calls him, lived in Brisbane with both Johnny and Michael in the late 1970s.

‘You know, they were so different; they don’t look like brothers,’ he says. ‘But they had the same absurdist sense of humour. Michael would just laugh at anything, and Johnny was the same. Everything was funny. And they were both very musical. Michael wasn’t a better musician, but he was just more comfortable getting up in front of people on stage. I think Johnny had trouble with that, though I’m not sure. Johnny was the outsider, and Michael was very protective of him.’

I soon found that Willsteed’s recollections fit a pattern. There is no shortage of people eager to talk about Michael’s charisma and his virtuosity as a musician; he’d played in a number of bands in Brisbane and Sydney and found some minor success with the Riptides. Yet the arc of Michael’s story is more tragic than mysterious. During the 1990s, Michael parked his own musical ambitions, got clean and became a father to two daughters. His death from a burst stomach ulcer at forty-three was totally unexpected.

Johnny was far more enigmatic. He killed himself five months shy of his thirtieth birthday, leaving behind no children of his own. He is survived by his father, who takes lithium to treat a bipolar disorder, and his mother, who is on Prozac to take the edge off depression. My mum, the last surviving Gorman sibling from that marriage, has long wondered about what might have gone undiagnosed in Johnny. She frames her brother’s story with questions around generational inheritance and mental health. Johnny’s drug use, whether illicit or prescribed, can be read as both a catalyst and a sedative for his paranoia, agoraphobia and constant depression.

In truth, there is a lot we simply don’t know. This essay is the beginning of my attempt to piece together the life and death of my uncle, for the simple purpose of honouring his memory and the memories of those who loved him. After conducting more than thirty interviews and reading through numerous old letters that Johnny had penned to friends and family, it’s clear that he had a disrupted childhood and battled constantly with drugs and alcohol. His troubled state of mind was never far from the story.

JOHN EDWIN GORMAN was dragged into the world by a pair of forceps on Christmas Eve 1958, wailing and covered in bruises. He was a cyclone of a child. He would rock back and forth in his cot, bang his head against the wall and turn somersaults on the floor. His mother, Shirley, tried to soothe this hyperactivity. His father, Barry, was too busy to notice.

Neither of them had had much preparation for marriage or parenting. Barry hated his own father, a railway worker from Hughenden and an abusive alcoholic. Shirley’s mother had died when she was seven and Shirley had lived an itinerant life, following her dad from one outback mining town to another.

The union of Barry and Shirley was one of struggle, displacement and constant apprehension. They tried their best to raise three children – Michael, Johnny and Cathie – while also battling their own mental issues. When Johnny was about to enter high school, Shirley had a nervous breakdown and walked into oncoming traffic. Cars screeched to a halt and she was taken, unharmed, to Prince Charles Hospital. She moved to Mount Isa soon after, divorcing Barry and leaving the children in his care.

The effect on Johnny, the middle child, was profound. He penned heartfelt letters to his mother that invariably ended with a plea for her to ‘come home soon’. In his diary, he printed I-L-O-V-E-M-Y-M-O-T-H-E-R on consecutive pages so only he could read its message, and at night he would sit up in bed reading Shirley’s letters over and over again.

Yet Johnny grew no closer to his father. Barry, now a single parent, had worked long hours at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research while studying to become a scientist. He’d unsuccessfully contested two elections for the Labor Party in the late 1960s and, in 1973, spent time in South Africa studying viruses. After he returned to Brisbane, he suffered a mental collapse and was taken to Belmont Hospital, where he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Even after all these years, Barry doesn’t know what happened to Michael and Johnny while he was in hospital. ‘When I came out, they were gone,’ he recalls.

There are gaps in this part of Johnny’s story. What we know for sure is that this was the beginning of a period of uncertainty in his life. With an adolescence marked by instability and separation, by the age of sixteen he’d been expelled from boarding school for stealing milk money and had witnessed his family fall apart. In 1974, neither Shirley nor Barry were in the picture and Cathie was enrolled at boarding school in Brisbane. But there are two women – Glenys Mann and Jude Rowell – who have strong memories of Johnny from Newmarket State High School.

Jude, three years younger than Johnny, remembers a sweet, happy teenager. She can still picture his curly black hair, his distant blue eyes and the Hawaiian shirts he wore, always with a packet of Benson & Hedges cigarettes parked in the breast pocket. Jude lived in Enoggera with her older brother, Tony, and their elderly widower father, Gus. Left to their own devices, Jude, Tony and Johnny would cut school, catch the bus into the city and rifle through albums at Rocking Horse Records or poke around a hippie store they called The Bong Shop. Tony introduced Johnny to the Sensational Alex Harvey Band. Johnny taught Tony a few chords on the guitar.

‘We used to call Johnny “Zap”,’ says Jude. ‘He was a really funny guy, and there was something about him that was special and beautiful and soft. I think Zap had a connection with Tony and I because we had a very old father and no mother. Maybe Zap was drawn to that because he was also from a fractured home? We were sort of like kindred spirits.’

Yet there was a loneliness to Zap that Jude found intriguing. He was a drifter. Sometimes, he would crash at her place for several nights in a row. Other times, he would return to a small room in an old house on Constitution Road in Windsor, where his brother Michael also lived.

Glenys, a year older than Johnny, remembers him very differently. ‘We knew of him as Michael’s brother,’ she says. To her, Johnny was a pest: naughty, antisocial and deliberately disruptive. And while Glenys does recall Michael living on Constitution Road, she is adamant that Johnny didn’t live with him permanently. Johnny, she says, ‘was like a will-o-wisp – he just came and went.’

According to Glenys, both Michael and Johnny seemed lonely, with only each other to rely on. ‘There was a stage where Michael and Johnny didn’t have anywhere to live, so they stayed at this boarding house over at Gordon Park,’ she says. ‘When it came to dinner and all the food was put out on the table, basically Michael and Johnny got very little of it because these older, single men that lived in the other rooms would just eat everything. They didn’t fit in there at all.’

The stark differences between Glenys’s Johnny and Jude’s Zap reveal a rootless young man oscillating between darkness and light. While Glenys found Johnny difficult to relate to, Jude felt almost as if Zap was becoming part of her family. Then one day, he disappeared from her life as suddenly as he had entered it. ‘It was awful for us,’ says Jude, ‘but we never, ever stopped thinking about him. We always wondered where he was and what had happened to him.’

It is difficult, after more than forty years, to answer this question. The most plausible explanation is that by late 1976 Johnny and Michael were both fully immersed in Brisbane’s emergent punk scene. An early edition of the punk fanzine Pulp includes an article about the Leftovers, one of Australia’s most notorious punk bands. It reveals that the band had acquired ‘the services of two brothers, a drummer and a rhythm guitarist’. Michael was the drummer, Johnny the guitarist.

Both boys were perfect candidates for the disaffection and rebelliousness of punk. As children, they’d listened to their mother’s Pete Seeger and Joan Baez albums and bashed around on her acoustic guitar. They’d received a political education of sorts from their father, who refused to allow them to stand for ‘God Save the Queen’ at the cinema. Johnny, in particular, had a torrent of pain and anger that needed a focal point. Much later, in a letter to a friend, he described his expulsion from school, his ‘disownment’ by his father and his separation from his mother as ‘the chain of events’ that led him to music. ‘So in this boredom and chaos,’ he wrote, ‘[I] took to playing guitar to show all how I have been wronged.’

As a musician, Johnny was never as confident or as versatile as Michael, but he maintained a singular focus on his Hagstrom guitar. He would remove the D string and detune the others, creating grungy, industrial noises that sounded like he was doing the work of both the guitar and the bass. This love of effects and a desire to create tortured sounds sometimes put him at cross purposes with other members of the Leftovers. ‘We used to just plug straight in, turn everything up and bang away,’ says Ed Wreckage, the band’s lead guitarist. Johnny also had a softness that set him apart from his much tougher bandmates. ‘He was almost angelic, really; he had this little-boy-lost look to him,’ recalls Jim Goodwin, a photographer who documented punk shows in Brisbane.

What punk offered to young misfits like Johnny was a new world and a scene in which they could create their own identities. In many cases, the stage names they took were examples of normative determinism. In England, John Lydon the street urchin was transformed into Johnny Rotten, frontman of the Sex Pistols.

Likewise, in suburban Brisbane, Johnny discarded his teenage nickname, Zap, and adopted a new identity: Johnny Burnaway. The name, which he took from a minor character in Anthony Burgess’ cult novel A Clockwork Orange, served as both punk persona and an accurate description of his future. His sudden departure from Jude’s life was the first of many disappearing acts.

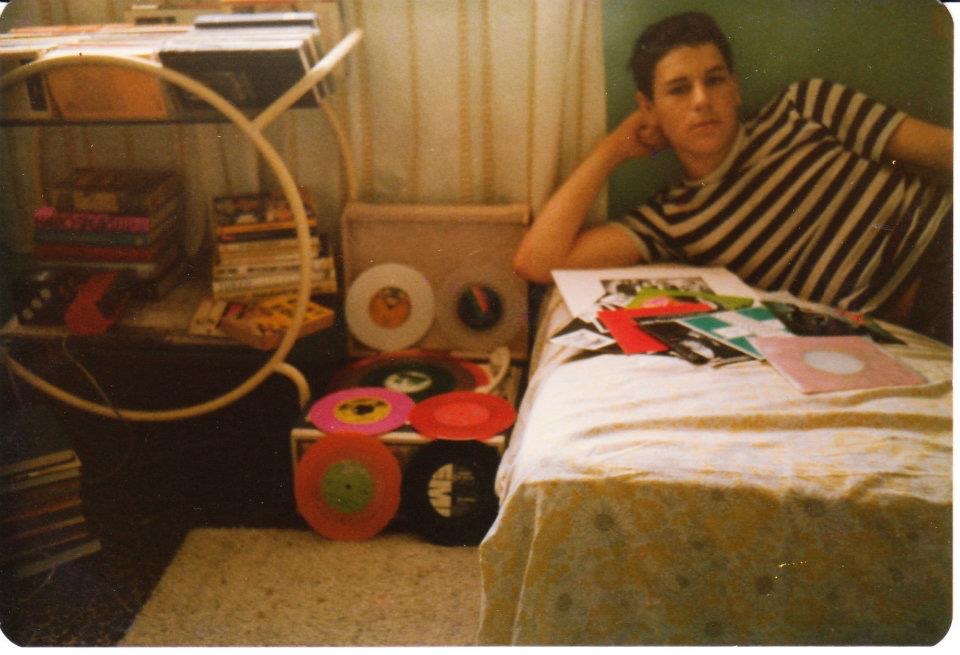

Johnny (supplied)

JOHNNY HURLED A crate into the window of a pawn shop and watched the glass shatter. Adrenalin pumping, he burst inside, stuffed as much jewellery as he could into a suitcase and hastily strapped the case down to a motorbike, fingers trembling with the clip. Hopping on the back of the bike, he and his accomplice drove south, past the clubs and strip joints of Fortitude Valley and onto the Story Bridge. Johnny felt the suitcase shift behind him as they rocketed over the Brisbane River and looked back, mesmerised by a shower of jewellery cascading through the air and onto the roadway. Undeterred, his accomplice gunned the engine and they took off, stopping only to steal petrol as they made their way a thousand kilometres further south to Sydney.

Or at least that was the way Johnny later described this incident to his friend Roger Norris. ‘With some of his stories, I wasn’t sure if they were 100 per cent truthful or not,’ admits Roger, four decades later. By all accounts, Johnny lived the life of a chancer and a thief when he arrived in Sydney, stealing from shops and house parties, friends and strangers. Yet any riches he gained never seemed to last long; as far as anyone can remember Johnny was broke and always on the lookout for a new scheme.

Although there are gaps throughout Johnny’s story, we do know that he was already heavily into drugs by the time he moved south in 1980. Cathie recalls finding him comatose in his bedroom one afternoon in 1979, with a handful of red pills on the bedside table. She vividly remembers the doctor advising the family that Johnny might suffer long-term brain damage from this incident. He was discharged from hospital a week later – seemingly unaffected by the overdose – but from that moment, the link between Johnny’s drug use and his psychological state was fused in Cathie’s mind: Did Johnny use drugs as a treatment for pre-existing issues, or was he mentally unstable because of his drug use?

The after-effects of substance abuse left a trail of destruction among many of the people Johnny was associated with in Sydney. Many of his peers – including Mary Callaghan, his girlfriend at the time – are now dead. But Fran Weidersatz, a close friend to my uncle and Mary, is still alive. She laughed when I asked her if Johnny had mental health problems. ‘I’m sure he did – I’m sure we all did,’ she says. ‘It wasn’t something that people got seen to, back then. You just kind of put up with it and drank and took lots of drugs.’

According to Fran, Johnny was depressed, highly self-conscious and constantly paranoid. She met him in 1980 through Mary, who was in the process of shooting Greetings from Wollongong, a film about youth unemployment during the recession. Johnny wrote a couple of songs for the soundtrack and helped out a bit on set – though he spent much more time playing Space Invaders. He lived, more or less, on a diet of Vegemite sandwiches, beer and shots of heroin. When Mary overdosed and went blue in the face, Johnny had to slap her and drag her around the flat to rouse her. He wrote letters to virtually everyone he knew, which, as he described in one, ‘killed the guilt bird and the sparrow of boredom in one fell swoop’.

Many of those letters were addressed to his mother, Shirley, or to Gary Warner, an old housemate from Brisbane. Shirley keeps her letters from Johnny in an old cardboard mailing box; Gary keeps his in a storage unit in Sydney. They were written on sheets of foolscap, postcards, notepads with company letterheads and A5 pieces of mint green paper. One postcard to Shirley included a quote about marriage from Anne Summers’ book Damned Whores and God’s Police; another was written on the back of a handbill to Against the Grain, an underground film Johnny had worked on.

As a teenager, Johnny had written countless letters to his mother to bridge the physical space between them. By his early twenties, his letters had a far more introspective tone and read more like private diary entries than correspondence. He described a dream where Robert Mugabe thought Mike Willesee was the prime minister (‘because Mike wanted the exclusives’) and one where he met a woman who was convinced that he was a warlock (‘we had a good rave about Al Crowley, feminism, politics and resigned to meet in a later life’).

Johnny’s prose was engaging and humorous, even as he was candid about poverty, drug addiction and emotional disintegration. The common theme was one of relentless self-examination and an obsession with psychological health. In one letter to Gary, Johnny wrote of his agoraphobia, indecisiveness and ‘unbearable self-pity’ before finishing:

Someone said the only cure for mental pain is physical torture. He signed off, then pushed the biro fully up his nose. Love John.

The letters read as if Johnny was searching for a diagnosis: he wrote about Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy, Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor and Arthur Janov’s The Primal Scream. Midway through reading Janet Malcolm’s A Critique of Psychoanalysis, he wrote to Shirley:

I took a moment to reflect about childhood influence in choosing a mate and it occurs to me that Mary is ½ you telling Dad to soak his head, and ½ Dad telling me he (she) still likes me (me) regardless of intellect. Even the name is a mixture of Mummy and Barry. Now if I could just find a girl called Barley I’d be happy.

When Johnny and Mary broke up in 1982, Johnny retreated to Brisbane and met Cheryl Wilson, who paid for them to see the Teardrop Explodes at Cloudland. Sometime during the set, he did the Johnny Burnaway, disappearing without a trace and turning up again months later without explanation.

Cheryl was different to the women Johnny knew in Sydney, who chopped their hair short and had sophisticated ideas. She wore her hair long like a ’60s hippie and lived with her parents in unfashionable Sunnybank. They both felt like outsiders and were happiest doing daggy things like shopping at garage sales or visiting Sea World. ‘I wanted it to be romantic,’ remembers Cheryl, ‘but John and I were really more great friends rather than lovers. There were times of sex, especially when we got into the drugs, but often he would just want to hold my hand during the night. He was the one I trusted enough to try heroin with, because I wanted to do it my whole life and I knew he would look after me if anything went wrong.’

But those outside the vortex of drugs were increasingly troubled by Johnny’s erratic behaviour. One night in late 1982, Johnny arrived at his mother’s place babbling and transfixed by his own paranoia. He crawled under the piano and started shouting at the voices in his head. This incident, which occurred three years after his first overdose, looms large in Shirley’s and Cathie’s understanding of Johnny’s demise. Shirley panicked, remembering her own and her ex-husband’s mental breakdowns, and committed her son to the insane asylum in Wacol. Cathie, holidaying in London at the time, flew back home as soon as she heard the news.

The doctor’s assessment of Johnny remains a mystery. Nobody in the family has his medical records and the facility, now relocated and rebadged as The Park Centre for Mental Health, carefully guards the privacy of its current and former patients. For years, Cathie and Shirley suspected Johnny’s behaviour that night may have been a schizophrenic attack.

All these years later, Cheryl provides a different account. She is adamant the whole episode was simply a bad reaction to some pills Johnny had taken. ‘We’d gone out clubbing that night… I was taking diet tablets, which was a bit like speed,’ she recalls. Johnny took a few, she remembers, and went ‘a bit strange’. Again he did the Johnny Burnaway, disappearing without explanation and heading to his mother’s place. The first call he made, after he’d sobered up and found himself in Wacol, was to Cheryl. They were hatching an escape plan when the doctors granted Johnny his freedom.

The drug use continued. After Johnny returned to Sydney, he sent Cheryl little parcels of smack and wrote of its deleterious effects on his brain and his finances. ‘Someone should make heroin illegal,’ he mused. He was lonely once again and consumed by self-doubt and inactivity. Meanwhile, Michael – who had dropped the surname Gorman for Hiron, Shirley’s maiden name – was also living the low life of heroin and drink. But at least he was making progress in his musical career, playing with the Flaming Hands and the Riptides and appearing in film clips and music shows on television. Johnny had a few minor film credits, but he’d spent more time hiding under the bedsheets than he had on stage or in a recording studio.

‘All this lying down and taking it is atrophying my brain,’ he wrote to Cheryl in April 1984. ‘For the first time in years I looked inside and there were signs of life. Ideas taking root on erosion-damaged soil.’

Finally, when Cheryl introduced Johnny to her friend Roger Norris, something clicked. Roger remembers drinking with Johnny on the couch at his share house in Redfern, listening to records and watching Elvis movies. He recalls Johnny dropping the needle on ‘Never Understand’ by the Jesus and Mary Chain. The track was everything they loved: a discordant wall of sound, loads of feedback on the guitar but with a hint of ’60s melody underneath. Chuckling, Johnny turned to Roger and said, ‘We should start a band like this.’

Roger, like Johnny, was a refugee from Bjelke-Petersen’s Queensland. He was bored and depressed and had been in search of new inspiration since the dissolution of his first band, Other Voices. He had never heard Johnny play before, but he knew of the Johnny Burnaway persona and he trusted Johnny’s eclectic ear for music. ‘I’m ready when you are,’ he said.

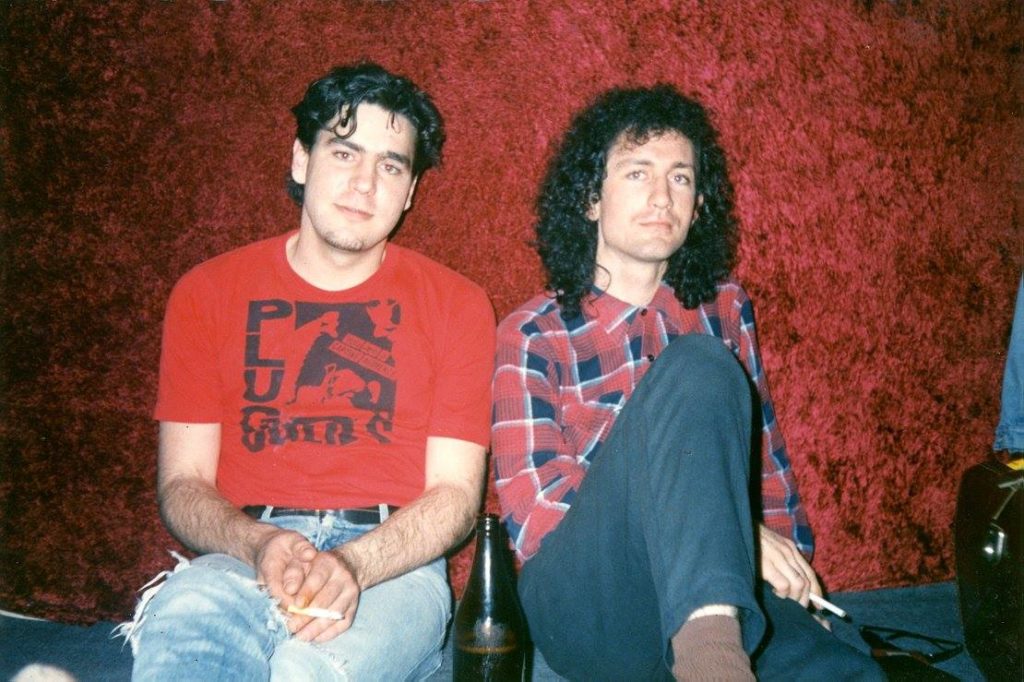

Johnny and Roger (supplied)

JOHNNY LIKED THE look of Tina Stevens from the moment she turned up at the rehearsal room flanked by six girlfriends and a dog. They rolled out of a big white Kombi van, set up her drum kit and Tina started to play. At nineteen, Tina was much younger than Johnny, Roger and bassist Wayne Baker, but she was unpretentious and fluid on the drums. After the audition Johnny walked over and rested his hand gently on her shoulder. ‘That was great,’ he said, and Tina knew she was in the band.

The Plug Uglies took their name from a New York street gang and wrote intelligent, original songs inspired by what Roger calls ‘Sydney’s golden decade of unemployment’. At rehearsals, Johnny would turn up with a guitar riff for Tina and Wayne to flesh out, and while they jammed Roger would squat down, scrawl some lyrics on a sheet of paper and find a way to bend the poetry around the melody. The first song they wrote together was ‘Dipsomania (The Drinking Song)’, which featured the call to arms ‘If drinking, drinking is a sin/I’m damned, so let’s get on with it.’

Their first gig was at The Music Cafe in Kings Cross in 1986. ‘Johnny was raring to go: he was clean, he hadn’t taken drugs and he was going to make this a really great gig,’ recalls Roger. But Wayne was catatonic after accidentally taking downers instead of uppers and Johnny, the boy scout of the abyss, needed to race up to the corner, score some speed and boot up his bassist so that the gig could proceed. ‘I mean, that was the kind of band we were!’ Tina later told music journalist Bob Blunt.

Like most bands, the Plug Uglies went through different phases as members came and went, but Roger and Tina were constant. Roger is now a successful advertising creative and Tina an award-winning artist who exhibits her work internationally. ‘I carry the Plug Uglies deeply inside me,’ she says. ‘None of the bands I’ve been in since compare to the Plug Uglies. I could never replicate that feeling, whatever that feeling was.’

Roger also remembers that rush. He now lives in New York with his partner and their son. The walls of his apartment are adorned with old band posters that he and Johnny designed all those years ago. ‘When John and I made music, those were some of the most sublime moments of my life,’ he says. ‘When you’re creating a song together, it’s such a powerful feeling. I think that also exists in other art forms – in writing, in visual art and even, in a limited way, in advertising. But with music, the hair would go up on the back of your neck.’

For Johnny, the Plug Uglies were the zenith of his on-off musical career. After so many years of misdirection and social anxiety, he finally belonged to a band with people that he liked and that liked him back.

Yet as Roger tried to land a record deal, Johnny’s contradictory behaviour continued. One day he was broke; the next he would turn up with a fat wad of cash he’d found ‘under the floorboards’. He would borrow a friend’s guitar for a gig, then turn up to the next practice session with a new guitar stolen from ‘some rich kids in Paddington’. When Michael organised for record executives to check out his brother’s band, Johnny did his best to ruin the opportunity, first by hiding under a parked car and refusing to come out, then by launching into a fifteen-minute version of an obscure Cajun folk song. Roger was frustrated, but he tried not to be judgemental.

‘Roger and I didn’t touch heroin; we were not of that persuasion,’ Tina explains. ‘We lived with it being around but we were also impacted by it. They were dark and exciting times. In that counterculture you could do what you wanted and almost hide within it. You could be the mad, drug-taking guy who plays awesome guitar in a band. It was completely accepted. But as time went on, I started to feel sad about Johnny because I had trouble seeing him in the distant future.’

A decade of alcohol and substance abuse was taking its toll on Johnny. Photos from 1986 and ’87 show his face craggy and scarred. He was tied up with an on-again, off-again girlfriend who was also an addict and there were stories of them spiking people’s drinks in order to steal money for drugs. He also stole money from a flatmate, Susan (not her real name), crashed her car and refused to move out – even though he wasn’t paying rent.

Cathie knew that her brother was struggling. In late 1987, she was pregnant with her first child and renting an apartment on Bondi Road. Sunlight would stream through her bedroom window, bringing with it the smell of salt and surf. She remembers Johnny sitting on the end of the bed, mesmerised by her swollen belly. ‘He asked me if I’d come up with a name yet,’ Cathie recalls. ‘I told him if it was a girl, I’d call her Chelsea. But if it was a boy, I said I’d call him Jack, because Jack is the nickname for John.’

Johnny grinned and placed his ear to her stomach, listening for a heartbeat. This was the lovely side of her brother, the side that Cathie remembers most. But she knew his errant side, too. ‘I often felt like I was his big sister, not his little sister, because I was always telling him to get a job,’ she recalls. ‘I just wanted him to settle down and live a normal life.’

But the letters Johnny wrote to Cheryl suggest he didn’t see himself as a likely candidate for fatherhood or domesticity. ‘I felt an urge last week to get married but there wasn’t anyone immediately at hand and it passed on,’ he joked in one. In another, he wrote of a desire to raise a child, before admitting that he’d probably ‘lose all interest in it after two days’.

Cathie gave birth to a baby boy on 4 February 1988. As promised, she named him Jack Edwin Gorman, after Johnny. At the naming party, in Elizabeth Bay, she thrust Jack into her brother’s arms. Photos show Johnny cradling his nephew – my older brother – and looking awkwardly at the camera. As the day wore on, he got drunk and started abusing other guests. Horrified, Cathie escorted him out of the apartment and told him to go home. Watching him walk away – his feet dragging, shoulders slumped – her anger immediately subsided. She wished she could hug him and invite him back inside. Instead, she waved sadly and let him go. She would never see him again.

The Plug Uglies (supplied)

ON THE FINAL day of Johnny’s life, 5 July 1988, Roger chauffeured him around the inner suburbs of Sydney. They hung out with Tina while she played the drums. They dropped into Michael’s share house in Darlinghurst. They had dinner together in Surry Hills and, as usual, Johnny drank too much bourbon. As Roger drove him back to his squat on Parramatta Road, they agreed to meet early the next morning to print hundreds of band posters. When Johnny said ‘I’m going to kill myself’ as he got out of the car, Roger thought he was being maudlin and told him not to be stupid.

‘You can have my records,’ said Johnny.

‘I don’t want your records,’ said Roger, putting the car into gear. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow.’

When Johnny didn’t show up for the morning poster run, Roger wandered over to Parramatta Road and pushed through the back door of the terrace house. He found Johnny hanging from an orange cord tied around his neck, his hand cold to the touch. Roger turned and ran – around the corner to Glebe Point Road and into Badde Manors café, where his friend Elisa Hall worked. ‘I was in the kitchen when Roger came in and told me what had happened,’ remembers Elisa. ‘We called the ambulance and then we went back to the house. We waited there until the ambulance arrived, and Johnny was hanging there the whole time. He had odd socks and holes in his shoes.’

The next day, Johnny’s friends gathered for a drink at Elisa’s place. Roger sank one beer and then another. He thought of the empty bottle next to Johnny and the silver packet of tranquillisers the police had found in his belongings. He looked around, frustration rising at the sight of Johnny’s friends disappearing into their own cycles of trauma and self-medication. He didn’t want to blur Johnny out; he wanted Johnny to be there, a cigarette in one hand and a can of VB in the other.

Roger put down his drink, said goodbye to Elisa and returned to Johnny’s squat. The house was dark and cold. Tears in his eyes, he began stacking Johnny’s records. It wasn’t the complete collection – some had already been stolen, others hocked for quick cash – yet they were a lasting physical connection to his dead friend. Replaying Johnny’s final words in his head – ‘You can have my records’ – Roger stopped and stared at the spot where he’d found Johnny the day before. ‘I just felt terrible, like I was Judas collecting coins,’ he says.

Throughout his life, Johnny had penned so many letters to family and friends in an attempt to make sense of his own mental fragility. Yet in death, he didn’t leave a note to explain his final act.

Naturally, this invited speculation. The most likely scenario to Roger is that Johnny killed himself because he was miserable. He knew Johnny admired the work of Antonin Artaud, a French avant-garde essayist who wrote of suicide as an act of self-realisation. ‘He was constantly saying he was depressed and that suicide was sort of reasonable,’ Roger told police at the inquest into Johnny’s death.

But there are other theories, too. Johnny was a heroin addict during the height of the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. Intravenous drug users were in the high-risk category for infection. When Johnny’s body was taken back to Brisbane to be buried, the undertaker wrapped him in protective plastic and refused to allow the family to give him a kiss goodbye. Cathie recalls being told that it was a precautionary measure in case Johnny was positive for hepatitis or HIV. It seemed odd to her at the time, but that information – coupled with her knowledge of Johnny’s subterranean lifestyle – got her wondering. She knew he’d injected heroin using shared needles. And Johnny had also intimated to her that he worked occasionally as a prostitute to finance his drug habit. Now, one lingering question for Cathie is if Johnny knew that he was dying.

Or was he looking for a way out? Ed Wreckage, one of the last surviving members of the Leftovers, says that Johnny was in trouble with the law. ‘The story was that John was going to jail when he died. He had a pending jail sentence,’ says Ed. This claim needs further investigation, but Johnny was a notorious thief. One of his old flatmates, Susan, says he was arrested for burglary in 1987 and only avoided jail time thanks to a reference she’d written for him. The most compelling piece of evidence, though, is Roger’s statement to the police inquest, which acknowledges that Johnny was supposed to meet a parole officer the day after his death. After all this time Roger can’t recall why.

And so nobody knows what Johnny was thinking in his final moments or why exactly he decided to take his own life.

Johnny’s funeral in Brisbane had no priest and no ceremony. As the coffin was lowered into the ground, Michael took a ring off his finger and threw it in after his dead brother. Others tossed in cigarettes and coins. ‘Get yourself a drink, John,’ one said. Only much later did Cathie find out that he had wanted to be buried to the Beach Boys’ ‘God Only Knows’. But in the end, the messy and incomplete farewell was a fitting tribute to the life and death of Johnny Burnaway.

In the weeks that followed, Michael joined the Plug Uglies. For Roger at least, band rehearsals and gigs felt almost like group therapy sessions with him and Michael playing Johnny’s songs. But it was never quite the same without him. ‘I was genuinely awed by his musical ability, even though he made out as if it was nothing,’ says Roger. ‘Johnny got into music and drugs and petty crime and people tend to put all those things together, like they’re causal. But I think music gave him richness and purpose to a life where he often felt rejected. A lot of things killed Johnny, but music wasn’t one of them. Unfortunately, the music wasn’t enough to keep him alive.’

Perhaps Johnny wanted his music to outlive him. In July 1989, one year after his death, the Plug Uglies released a six-track EP from the songs recorded before Johnny died. The album title, Knock Me Your Lobes, was taken from a Lord Buckley song from 1955 that begins:

Hipsters, flipsters and finger poppin’ daddies

Knock me your lobes.

The liner notes include a thank you to ‘Panadeine Forte’ and ‘pawn brokers everywhere’, and a photo of Johnny taken at the recording studio graces the cover. In an interview with The Sydney Morning Herald in 1989, Michael provided a fitting final word. ‘It’s his record,’ he said. ‘But we don’t want any mystique. It’s just a statement of what he was capable of.’

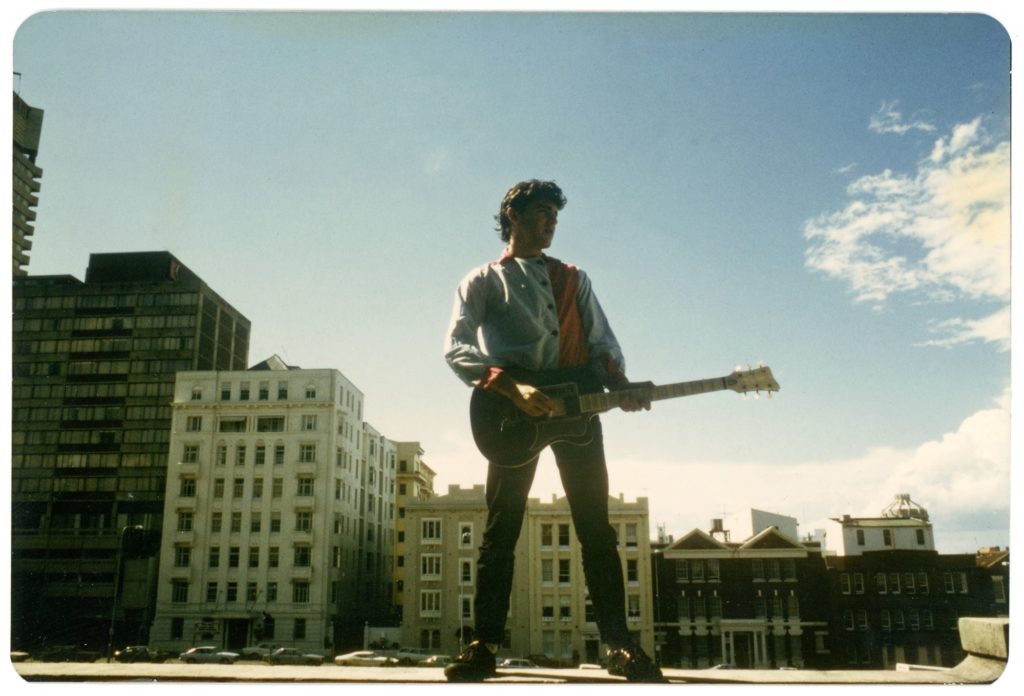

Johnny in Kings Cross (supplied)

IN THE YEARS after Johnny died, my mum had a vivid recurring dream in which Johnny was still alive. ‘I’d say, “You’re not supposed to be here, you’re dead,”’ Mum recalls. ‘And he would respond, “No I’m not, I’m here.” I had that same dream over and over again. But then Michael died and the dream stopped, and I never dreamt about Johnny again.’

I live in Brisbane now, one street over from one of Johnny and Michael’s old share houses. My nan lives at the foot of the Blue Mountains, not far from her daughter, my mum. One wall of her retirement unit is adorned with photos of Johnny, Michael, Cathie and her grandchildren. In Brisbane, my pop talks to Michael every night in his head as he washes the dishes. On his bedside table, Johnny’s distant blue eyes stare back at him from an old vinyl copy of Knock Me Your Lobes.

The research into my uncle’s life, which began at Mum’s request, has only just begun. There are still more people to track down and, hopefully, more artefacts and stories to uncover. At this point, questions around his mental health remain unresolved and the exact circumstances of his death are unclear.

But for now, at least, writing this essay has helped Mum find Johnny’s burial plot at Hemmant Cemetery. And she’s asked his old friend Roger Norris to design a small plaque to mark its location so that Johnny’s friends and family can sit beside him and chat to him and ask him where he went.

Alongside the obligatory date of birth and death, there’s going to be a picture of Johnny with his guitar and a line that reads ‘Hipsters, flipsters and finger poppin’ daddies… Here’s Johnny Burnaway.’

Johnny Burnaway (clip shot and supplied by Gary Warner)

Share article

About the author

Joe Gorman

Joe Gorman is a writer based in Brisbane. His most recent book, Heartland: How Rugby League Explains Queensland, won the 2020 Queensland Premier’s Award...