Featured in

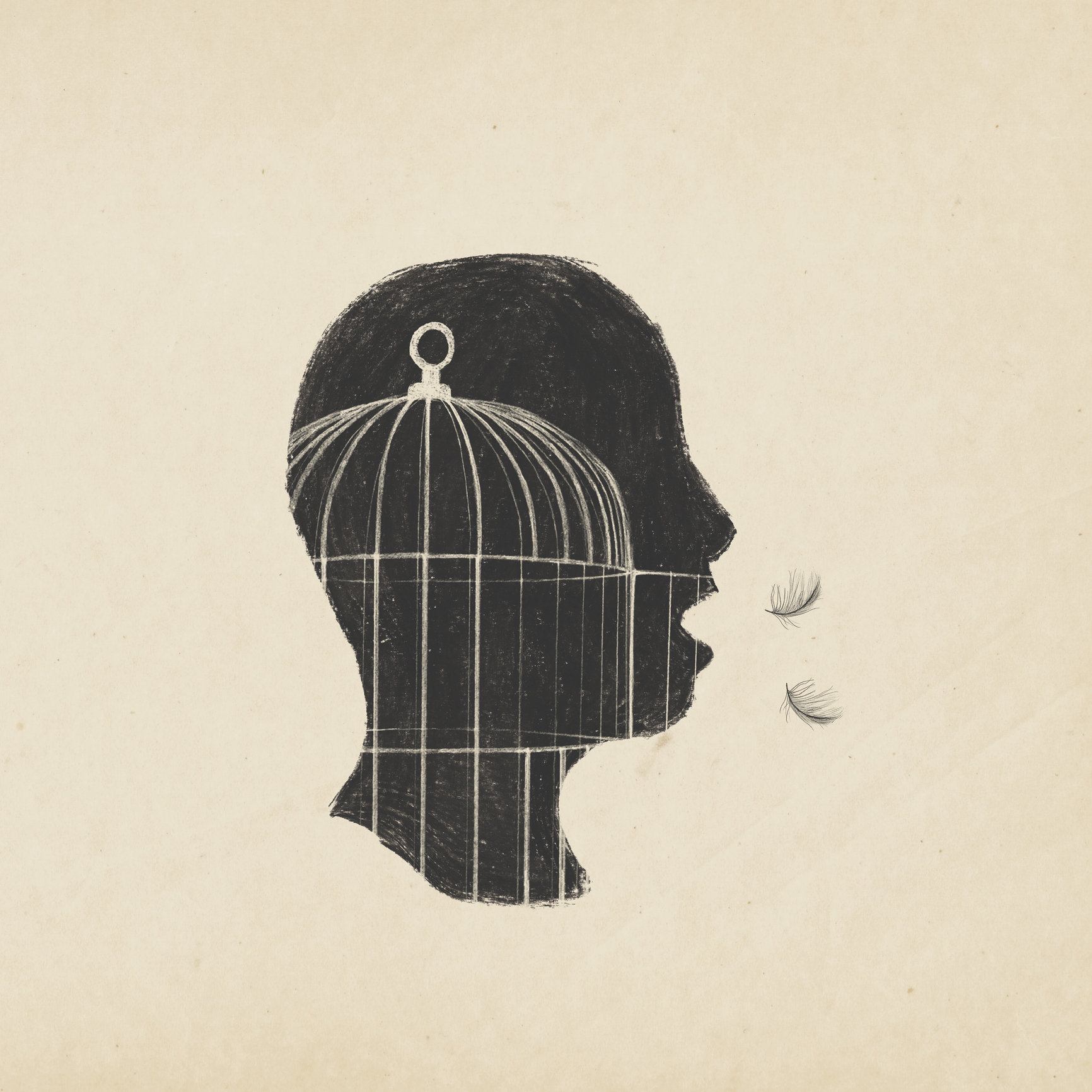

I’M CONSTANTLY PARANOID that the moment you put something into words you are slapping shackles on its ankles and wrists. This may strike the reader as ironic given that novels are my creative medium of choice, but where others can explain things in the span of normal conversation, I require the emotional insurance of 100,000 words.

Recently, I was translating the first poem in One Hundred Letters of Love, a collection by Nizar Qabbani, Syria’s ‘national poet’. It opens:

أريد أن أكتبَ لكِ كلاماً

لا يشبهه الكلامْ

وأخترع لغةً لكِ وحدكِ

I want to compose for you words

that resemble not words

I want to contrive – for you alone – language.

Qabbani goes on to lament the insufficiencies of all known tongues in describing love, an emotion that inspires dissolution and expansion – and one that language fetters. Worse yet, by translating this poem, I had subjected Qabbani’s love, already straining against Arabic, to the further restriction of English.

Writing is entrapment. Is it a lie to ossify a truth that is dynamic and plural, like everything in nature, in words? Is translation a double lie? If transcribing personhood into literature is reductive by necessity, then is translation a double reduction? On the writing podcast, Crafting with Ursula, author Lidia Yuknavitch says: ‘Rearrangements in meaning are life, and stasis in meaning is dead meaning.’ How then can you put anything into words without killing its meaning? How can you translate meaning without killing it twice?

ON THIS LAND that has, for many millennia, seen the flourishing of language upon language, and now finds itself home to a population of which almost 30 per cent were born overseas, translation is part of our national identity. Had early colonisers respected First Nations peoples enough to value their myriad languages, and the relationship of those languages to place and culture, the history of this country might have taken a less despicable turn. Globally, English’s dominance as a Western lingua franca presents a qualm to writers who grapple with being forced to express themselves in the language that has also been the instrument of their peoples’ dehumanisation.

Reaching to make contact with the impossibly alien is one of the most hopeful things a person can do; it is also one of the most human. At the climax of Ursula K Le Guin’s profound epic The Left Hand of Darkness, an envoy from Earth is stranded in Arctic desolation with a political refugee from a humanoid race. The two unlikely companions find each other unsettling and incomprehensible. Only after weeks of total isolation do they land upon a revelation: ‘It was from the difference between us, not from the affinities and likenesses, but from the difference, that that love came: and it was itself the bridge, the only bridge, across what divided us.’ This is the euphoria of two people tossing a rope to each other across the abyss of their entire lives.

This is also the euphoria of the novel. A novel begins in the outermost ring of a spiral. From the opening word, a writer embarks on the odyssey of slowly leading a reader to their idea – down and down, closer and closer. But a spiral coils forever; there is no centre. This ever-narrowing – but never-closed – distance between author and reader is all the space that gives a book life. It is in this space – untranslatable – that truth exists. This is where Yuknavitch’s ‘rearrangements in meaning’ are constant, where the reader continues the work of crafting a novel by interpreting it within the realm of their own ever-shifting identity. As Octavia E Butler puts it in the thesis of her novel-cum-manifesto, Parable of the Sower: ‘The only lasting truth is change.’

LABOURING TOWARDS A shared understanding is the most rewarding part of conversation, and the best novels are a conversation. If language is insufficient, good writing nonetheless manages to ‘contrive – for [the reader] alone – language’, as Qabbani wished to do, one that can act as a stepladder to the transcendence of language itself, towards the writer’s idea. It’s like teaching someone a dance until they are so fluent in its choreography that they can continue without a partner, without having to consider the next step, without music.

Here is where I see a solution to my Qabbani dilemma. It’s possible I was liberating his love by doubling the number of languages in which it existed. I was moving his boundless feeling from one jail cell into another, yes, but at least the cell had doubled in size.

More interesting than any cell, though, is how Qabbani revels in his chains. Half of his passion lies in its inexpressibility, in the romance of communicating his yearning within the meagre, prescribed bounds of an alphabet. The poem is built around the refrain, I want.

I want original sounds

from which emerge words

as emerge nymphs from the froth of the sea

as appear ivory chicks

from a magician’s top hat.

If ever he found his ‘original sounds’, his want would be dead. His love is animated by the act of reaching towards apotheosis and sustained by the knowledge that apotheosis can never be reached.

This paradox is familiar to me. Most translations of the Quran print their alternate language alongside the original Arabic. The effect is that, while reading the English, I am constantly reminded of some essence which escapes me. Certain chapters begin with sequences of Arabic letters – الٓمٓ – قٓ – يٰسٓ – the meanings of which have remained indecipherable to centuries of Arabic scholars, acting as God’s reminder that the Divine lies outside human creation; it cannot be defined. Truly original sounds can only be invented by a tongue that is infinite and exists way beyond what we could even conceive of as a ‘tongue’.

World-bound as it is, there is beauty in writing that strives with futility towards this infinite tongue. To write a novel without killing its meaning requires that I, like Qabbani, learn to revel in the truths I sacrifice, to leave space for entropy and the sublime. It requires conveying the insufficiency of language from within language, commemorating stories that have never been transcribed without allowing transcription to diminish their soul. In other words, to write requires that we translate and untranslate ourselves. Then, when all is done, we still never say what we mean.

Share article

More from author

Killing the poets

GR OnlineWhen asked in an interview what he feared most during this war, Palestinian writer Khalil Abu Yahia responded, ‘I fear that I will die without achieving my dreams. I want to complete my PhD. I want to rebuild my family’s house… And [my] biggest dream – to meet my [international] friends in person, to shake hands, to hug them. It sounds very simple, but colonialism disconnects people from the rest of the world.’