Featured in

- Published 20200505

- ISBN: 9781922268761

- Extent: 264pp

- Paperback (234 x 153mm), eBook

THE TALE OF a life doesn’t always start at the beginning, and sometimes it has to venture beyond the end. In between is a lot of awkwardness about changing physicality and impending mortality.

Such ideas wafted around in the back of my mind in the pre-dawn chill as light and warmth welcomed me through the sighing hospital doors. The day-to-day busyness was yet to fully develop as I walked past the receptionist secured in her booth. She smiled at me with a knowing nod.

She recognised that I was on my way into the bowels of the medical facility, to that basement room where unspeakable things were done.

I liked to go in the front entrance of the old regional hospital, where all the other normal people went in, even though I was permitted to enter the back way. I could have parked where the other service personnel stationed their vehicles. It would have been quicker, more expedient. But I preferred to jostle for a space in the main car park, as though this was more civilised.

The carpet squares of the foyer and main corridor were various shades of nondescript tan, ideal for disguising the otherwise disgusting stains that beset public buildings trammelled for years by careless footwear and grinding wheels as ageing trolleys, hospital beds and wheelchairs were manoeuvred around.

Eventually the flooring changed to sensible linoleum. As I passed by the hospital kitchen, I grabbed one of those funny paper hats designed to keep stray hairs out of food, or, as upstairs in the operating suites, out of the surgical field. For me, the need was reversed. Instead of protecting the environment from contamination, it was my hair that needed protection from the setting I was about to venture into.

I pushed open the heavy door that proclaimed ‘Service Personnel Only’ and descended the bare concrete stairs into the less glamorous parts of the building. Round the corner I went, along the windowless hallway lit eerily yellow from frugally spaced incandescent lights.

Looming at the end of the corridor was another heavy door bearing a warning sign: ‘Mortuary’.

IT SEEMS OMINOUS and creepy, but I’d arrived that day to do what I love to do. I’m a country doctor and, like many of my kind, a general practitioner with a special interest – a medical passion that many people might find confronting. No, not colonoscopies: autopsies.

I acquired my peculiar auxiliary field of expertise having trained in a bygone era when specialisation wasn’t so rigid. Once upon a time, not so long ago, any doctor could do everything. He, or less often she, would deliver babies, treat childhood illnesses, take care of adult diseases, manage injuries, perform surgery, look after old people and conduct post-mortems.

But modern medicine has moved on. Today, obstetricians deliver the babies, paediatricians look after the children, gynaecologists the women’s parts, urologists the mainly men’s parts and geriatricians the elderly. Adding to the orchestra is the list of ‘organists’: cardiologists for the heart, respiratory physicians for the lungs, nephrologists for the kidneys, hepatologists for the liver, ophthalmologists for the eyes and so on. Specialist anaesthetists put you into a coma so the variety of body-part-specific surgeons can take certain bits out and/or put particular substitutes in. But the practice of examining the human body to more fully investigate medical conditions and determine cause of death is a dying art.

If there’s one thing people feel more uncomfortable about than having a fibre-optic tube inserted up their bottoms, it’s their own mortality. This is despite the fact that the circumstances and process of dying are poised like cumulonimbus over our life and health the older we get, and dead bodies are everywhere on cinema screens, televisions, mobile devices and bookshelves. People are familiar with post-mortems, but mainly in fictional crime settings. Converting the autopsy into entertainment makes it easier for us to forget about the inevitable reality of our own death. In the hospital system, performing this procedure as a routine has fallen in frequency from more than 45 per cent of deaths to less than 3 per cent over the last forty years. There may be a plethora of actor pathologists, but the genuine article is harder to find – anatomical pathologists, who deal with surgical specimens as well as performing hospital post-mortems, comprise less than 850 of nearly 119,000 Registered Medical Practitioners in Australia at the moment. There are only about fifty forensic pathologists in the medical workforce.

How did such a thing happen in one generation? Advances in medical imaging and sample tissue processing have certainly contributed to doctors’ confidence in arriving at a definitive diagnosis without conducting a physical post-mortem examination. But it took correlating ante-mortem investigations with actual post-mortem findings to get to this stage. And this is still a work in progress, because disease patterns change and more techniques come online, such as immunohistochemistry taking light microscopy further and magnetic resonance imaging revealing different details from those shown by computerised tomography scans. The scientific method requires repeated testing for reproducibility and reliability. Even doctors and scientists get it wrong – they’re only human, after all.

Maybe it’s money. An autopsy is not considered the legitimate healthcare cost it should be. If someone dies in unnatural or suspicious circumstances, the death becomes a legal matter and is reported to the coroner. In an interesting twist, if a treating physician cannot write a death certificate when a natural death is sudden or unexpected, the case is also referred to the coroner. The expense of the post-mortem examination is then hand-balled from the Department of Health to the Attorney-General’s Department. These sudden deaths from presumed natural causes have taken on more significance in providing information about general pathology as the rate of hospital post-mortems has declined.

In Australia, the coroner – a legal professional, not a medically qualified one – can ask any doctor to perform a post-mortem examination to determine the cause of death in reportable cases. Usually this would be a medical specialist in forensic pathology. The autopsy is done to determine the precise cause of death for the purposes of appropriate prosecution, administration of justice and public health implications. But once again, because of money, even coronial cases are now triaged as to the need for a full physical post-mortem. Under the coronial system, autopsies to determine cause of death were often performed by general practitioners in rural and regional areas as part of their usual duties because they had enough experience and specialist pathologists were not available. When forensic matters became more complicated, the range of cases allocated to these country doctors was appropriately reduced to situations of sudden unexpected death due to presumed natural causes. This worked very well because these physicians were also treating living patients experiencing the full gamut of medical conditions with the potential to lead to death, and could thus provide timely feedback on community health. But as country hospitals undergo needed upgrades, they acquire more waiting areas for relatives, spacious disabled toilets – and no autopsy rooms, using the dwindling numbers of medical practitioners capable of performing autopsies as the excuse. Now, there isn’t anywhere to do a post-mortem examination even if appropriately skilled doctors were available.

As a consequence, the taxpayer has to foot the bill to transport the deceased to the city for an autopsy. The funeral is delayed to accommodate the return journey. The local treating doctor and the next of kin are less likely to receive rapid information about the reason for the patient’s demise. The Rural Clinical School is deprived of the chance to offer an ever more unique experience of the human body to their medical and nursing students.

BUT WE CAN improve our lot – perhaps even stay healthier for longer – by knowing what causes death, despite the discomfort provoked by facing our personal mortality. Some things once considered part of normal human experience have been reclassified as diseases. Some former diseases have been accepted as variations of normal. The greatest achievements in combatting disease and extending longevity have actually been though public infrastructure measures that supply safe, clean water, efficient waste disposal, adequate food availability and appropriate shelter.

When the quick killers of catastrophes and contagions are effectively managed, the population becomes prone to the slow killers: cancer and cardiovascular disease. In the circumstances of chronic disease, the interplay between environmental factors and genetic predisposition comes to the fore.

But people still die suddenly and unexpectedly from natural causes, and these cases don’t always receive the investigation they deserve. While I was performing autopsies for the coroner in a regional centre of country Australia, unexpected things were discovered in people who died of presumed natural causes, including some deaths that turned out not to be the natural result of a disease after all.

The correct term for the post-mortem examination is ‘necropsy’: to look at the dead. The more popular ‘autopsy’ implies looking at the self, although it’s usually translated to see for oneself. And it takes a certain kind of intestinal fortitude to undertake this work.

THE AUTOPSY ROOM in the old hospital was a bit like a bathroom: tiled, water-resistant, full of special plumbing and extractor fans, just on a more industrial scale. Instead of an enamelled bath in pride of place, there was a steel table with suitable drainage.

My mortuary technician on this occasion, as with previous ones, had already prepared the body, which lay naked under the strong examination lights. Once, this lifeless cadaver was a man in his mid-sixties, but the essence of the person was no longer there. The mortuary admission form filled out by the police documented the sad tale of how he suffered pain for several weeks before dropping dead when walking to the car that was to take him to the hospital. Whatever it was that killed him had yet to be diagnosed. He had left it too late.

No doctor could write a death certificate, as none had been involved in his final illness. The cause of his death was a mystery.

About 75 per cent of sudden natural deaths like this one are caused by conditions of the heart, 50 per cent by coronary artery disease in particular. But statistics are irrelevant for any particular individual. A best bet is not good enough, yet happens frequently when autopsies are performed infrequently. True, the average person these days is more health-conscious, or less tolerant of suffering, so seeks medical attention in a timelier manner. With our illnesses investigated and categorised, it is easier to make an assumption of the cause when we die, enabling a death certificate to be written with greater accuracy.

Conjectures were not helpful for this case. The coroner authorised a post-mortem examination to determine the actual cause of death.

So here I was, scalpel poised.

In contrast to the ever-smaller incisions made in modern surgery and techniques aided by fibre-optic technology, autopsy access is deep and wide. Nothing can remain hidden when the opening is from the Adam’s apple to the pubic bone. Every part is prodded and probed.

Unlike the representations we see on screen, encounters in real life engage all the senses. You see everything in natural living colour and three dimensions, hear in real time, touch to feel texture, consistency, density. And yes, olfaction is involved. The contents of a stomach smell like vomit, more or less. The contents of the large intestine smell the same as poo, because that’s what it is. If there is urine in the bladder, it smells like pee. Unwashed body parts smell the same whether the body is alive or dead. But the particular odour of decomposition assaults us less these days because the deceased are housed in refrigerated compartments to slow the process down.

Our senses are primed to detect change. Continued exposure to a stimulus results in ‘extinction’ – that is, the brain stops consciously registering the sensation. Our eyeballs constantly vibrate to retain our vision. If the eye is clamped still, the image we perceive disappears after a while. Fortunately for our sense of smell, if we remain in the vicinity of the odour source, it ceases to cause offence, unless we leave the room and come back in again.

Once adjusted to any initial olfactory unpleasantness, an autopsy is a marvellous experience. Interacting with a human body in such an intimate way leads to important discoveries that advance the knowledge and understanding of pathology and the intersection of health and disease.

We had only just started the autopsy on this unfortunate gentleman when it became apparent that something was badly wrong.

Normally, the abdomen is lined by a glistening, smooth, transparent membrane. Previous surgery may sometimes result in bands of scar tissue forming. These gum things up and stick parts together in abnormal ways. These tissue scars are called adhesions.

This man had no indication of abdominal surgery in the past, yet his abdomen had lots of adhesions. Closer inspection and palpation, looking and feeling, revealed that his bands were thicker, whiter, knobblier. I recognised this appearance. It was metastatic cancer, with crab-like arms stretching out to claw at and invade all the nearby normal tissues.

Clumps of secondary tumour had spread everywhere inside the peritoneum. It was an angry-looking neoplasm, eating away at the surfaces, causing ulceration and bleeding. It would be a potent source of pain. The cancer had spread further afield to his liver, lungs and lymph nodes, wreaking havoc wherever it went.

But where did it come from? Where was the original, the primary tumour?

It took a bit of unpicking – dissection, if you want to be technical – to track it down to a segment of the large bowel. In the part that goes from the lower right-hand corner of the abdominal cavity up towards the liver under the right ribs, the ascending colon was the origin of all this mayhem: bowel cancer.

These growths start in the lining of the bowel and may first form a polyp. If the lump of abnormal cells remains undetected, it continues to grow in all directions – into the central bowel lumen and into the muscle layer of the bowel wall, through the bowel wall and directly into the abdominal cavity. This man’s cancer had also gone right around the circumference of his bowel at the level of origin. Cancerous cells travelled in the blood vessels and lymphatic channels to other distant parts of the body, where they lodged like seeds to start another new growth – a metastasis.

This malignancy comes in at number six on the list of causes of death in Australians. Though lung cancer causes more deaths, bowel cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, behind breast cancer and ahead of prostate cancer. It has a five-year survival rate of 71 per cent.

But it is rarely responsible for a sudden and unexpected death like this one. At least on this occasion we could determine the reason for this man’s undiagnosed pain and the cause of his unexpected death by performing a post-mortem. But it shouldn’t have come to that.

Colon cancers on the right side of the bowel are less likely to cause early symptoms, such as a change in bowel habit or passing visible or invisible blood in bowel motions. Thus they are more likely to spread before diagnosis is made. Pain is a fairly late symptom in most cancers.

Given the adverse public health impact of this condition, effort and resources are expended to try to detect bowel cancer earlier, when it could be cured by surgery and chemotherapy if needed. Our taxes contribute to the distribution of kits, designed to uncover the occult bleeding that small cancers may cause, to everyone between fifty and seventy years old every two years. When you get the kit, you should use it. Don’t leave it too late, either. What would you prefer – a colonoscopy or an autopsy?

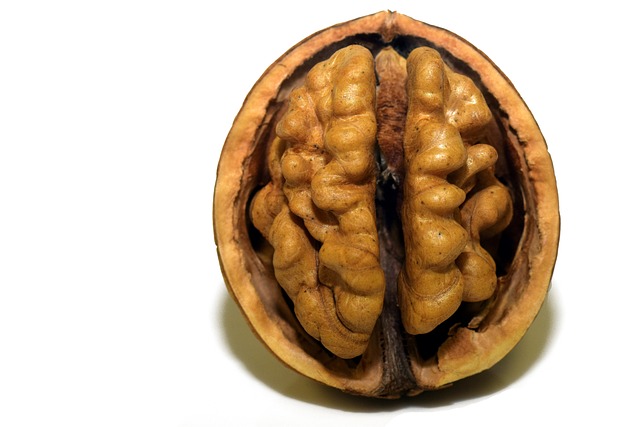

I LOVE THE full sensory experience of the post-mortem examination. Sadly, there are now few such opportunities for medical trainees to feel the light and spongy normal lung, or the heavy wet ones affected by oedema, or the stiff solid parts caused by pneumonia. Rare indeed are those who know what a human heart feels like when you hold it in your hand and trace the coronary arteries circling its surface, or peer into the depths of the abdominal cavity behind layers of intestines to where the kidneys lie resting on the lower ribs.

We can’t remove our innate fear of death or the uneasiness most of us feel at the prospect of delving into a real human body. But the autopsy – the act of ‘seeing for ourselves’ – will enhance our understanding of how we got to the end.

Share article

About the author

Meryl Broughton

After graduating, Dr Meryl Broughton did anatomical pathology for several years before going into rural general practice, where she performed autopsies for the coroner....

More from this edition

Killing time

Essay The days of our lives are seventy years;And if by reason of strength they are eighty years,Yet their boast is only labor and sorrow;For...

The delicate pleasure

GR OnlineNostalgia is often twinned with sentimentality, but many Baby Boomers I know...have an uneasy relationship with the food of their childhoods. Any discussion is ironically underpinned with acknowledgement that we deliberately left the corned beef and fairy bread behind...

Joining forces

Essay THESE ARE ANGRY times. The Earth itself is angry. Flames roar through the land, human tempers flare and the political world is angrier than...