Featured in

Linda Brescia, Persona and Performance in Everyday Life Series, 2014. Digital C-type print, photographic technician Alex Wisser

I AM LOOKING at Linda Brescia’s artworks and I’m thinking about these words: Domestic. Suburban. Mother. I am thinking about how they can be an insult. A slap across your face. A scar you wear into your future. When I ask her about these words she tells me a story: ‘I remember this absolute moment. I was standing under the shower. I was about forty and I thought, is this it? I had to do something for myself. It kills you. You have to have something.’ For Brescia that something was an art practice that was delayed by motherhood. ‘It’s a lonely space…as much as I love my children and family… It’s been a very lonely space for me.’

I’m about forty myself at this stage of my art practice and I’m at that point where being a mother and an artist does sometimes kill me and sometimes fuels my art. I’ve been watching Linda develop as an artist since I first met her as a resident at the Parramatta Artists’ Studios several years ago just after I’d had my first child. When I interrogated her and the other mother artists in Sydney’s west about how we (I?) could keep on making art she responded: ‘I consider myself a feminist but I’m the one who scrubs the toilets.’ In my mind that line is essentially what all her art is about – that seemingly contradictory position of being a deeply political feminist and knowing that at the end of the day you’re still responsible for cleaning the shit.

I think of her work Veiled Truth. She’s veiled in a long train of cleaning wipes sewn together, standing at the threshold to the suburban home. She’s both defiant and forward-looking, resolved to her fate but not particularly happy about it. I think she knows her future.

Linda Brescia, Veiled Truth, Persona and Performance in Everyday Life Series, 2014. Solvent ink digital print, photographic technician Alexis Wisser

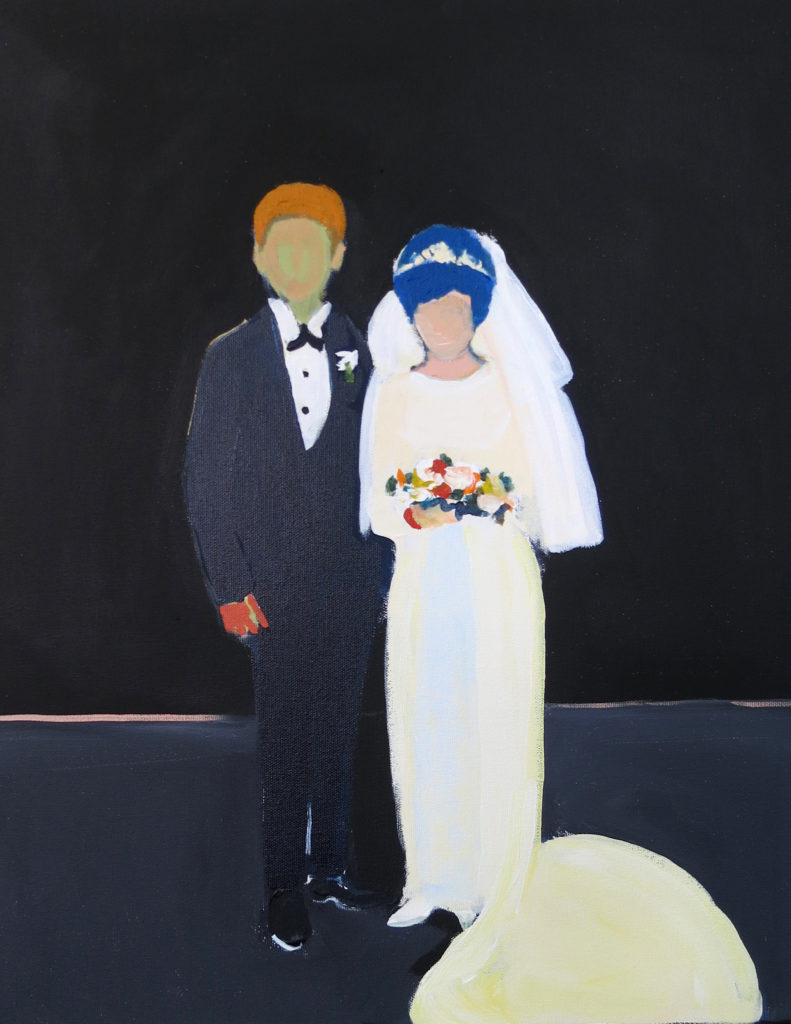

Linda Brescia, Before Series, 2014

HERE’S ANOTHER IMAGE of the bride from Brescia’s Before Series – the bride before her awareness of all the things that are to come. The later bride, dressed in her blue cleaning wipes, has had more time to consider what those words mean. Domestic. Suburban. Mother. As Brescia searches for a better material to speak these themes, she first has to stretch the conventions of what art is – and what art is made of. The materials that frequently appear in Brescia’s work – cleaning wipes and kitchen sponges, toilet cleaners and feather dusters – expose the comparative poverty of a canvas, or a piece of clay, as if regular artists’ tools can’t render feeling or emotion. They don’t say, this is what it’s like to be here, to be me. They don’t provoke, in the viewer’s fingertips, that visceral memory of scrubbing, an experience that, according to Brescia, ‘underlies the practical truths of domesticity in which material and social matters are cleaned up.’

Linda Brescia, Holding Up the Sky, knitted domestic cleaning cloths, cotton, wire, PVC pipe, diameter 260 cm. Photo by Garry Trinh, 2018

THE CLEANING WIPE is, of course, not just a literal object but a metaphor for talking about what it means to be a woman, a mother, someone making art from home. It requires a different kind of material to think of art while babies are clawing at your arm. Maybe it requires a different aesthetic. In Brescia’s work, domestic woman has fought back a little; the result is profoundly dignified and playful. I imagine these cleaning-wipe sculptures as dreamscapes, things that might have leaked from her mind into the world around her as directly as Dali’s clocks. They are a representation of the small things that govern our daytime lives and haunt our night-time dreams.

These sculptures speak to what domestic work means to a woman’s sense of self in the larger world; how that affects a woman’s relationship to children, mates, lovers, friends. They speak to its pleasures, pains, to the personal and political consequences of the endless work for which she is not paid. All these experiences are in an object made uncanny by Linda: by giving it new focus in a different form, she shows how overwhelming the domestic can be – how strange and unsettling an obligation it is for many women.

Linda Brescia, Too Much, 2008

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO divorce the domestic objects of this work from the domestic spaces they belong to. In this work the ordinary house that contains the ordinary objects becomes the strangest thing in the world. Look at the large size of the washing basket compared with the sculpture of the woman.

The basket is heavy, hard to carry. It’s menacing even. It speaks to the fact that the domestic is far from a neutral space. It’s loaded, not just with filthy washing but with the insurmountable weight of the work it requires physically and mentally – and the distance between Brescia and the art she (and all us artist mothers want) to be making instead. The proximity to these objects shapes our understanding of what Brescia is trying to say: a woman is dwarfed by her own washing basket. It’s funny and it’s playful too, as are many of her artworks when she reappropriates domestic materials.

Linda Brescia, Persona and Performance in Everyday Life, 2014. Solvent ink digital print, photographic technician Alexis Wisser

IN THIS WAY, the domestic is made exotic – but that exoticisation is also a kind of path towards taking charge of and telling one’s own story. The domestic becomes a space for the encounters and conflicts that shape Brescia and her relationship with her audience as well. She’s not just a suburban housewife – she’s got tits and bare flesh and she’s playing a deeply nuanced, complex and fiercely intelligent game with her audience. She’s messing with your head as well as pulling off her own. I am thinking about the kind of liberation that comes from turning a scouring sponge into an elaborate crown for your head, as Brescia does in Icon. ‘I’m interested in the things we aren’t aware of when we are looking after children,’ Brescia says. These images are a kind of fuck you: I contain multitudes.

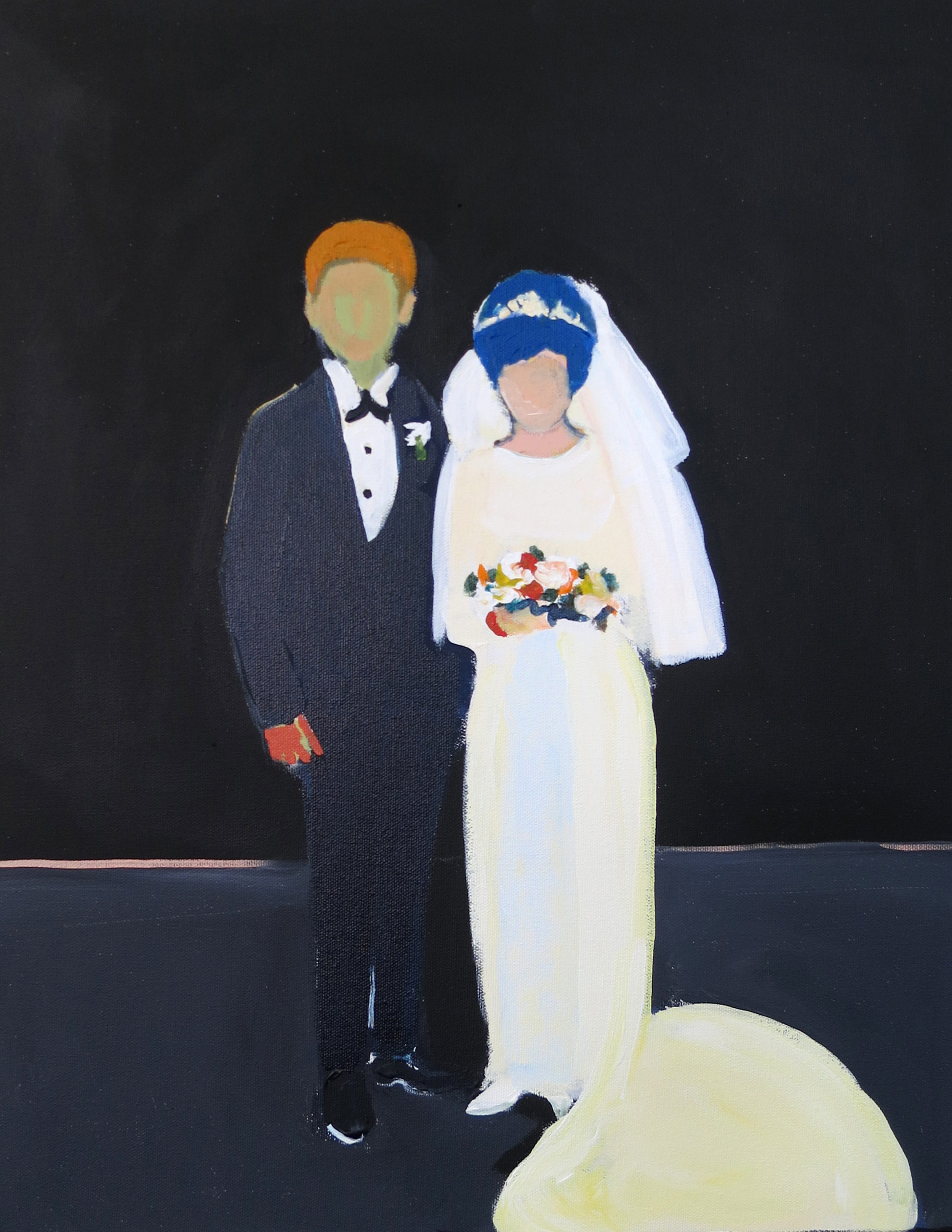

Linda Brescia, Family Secrets, 2014

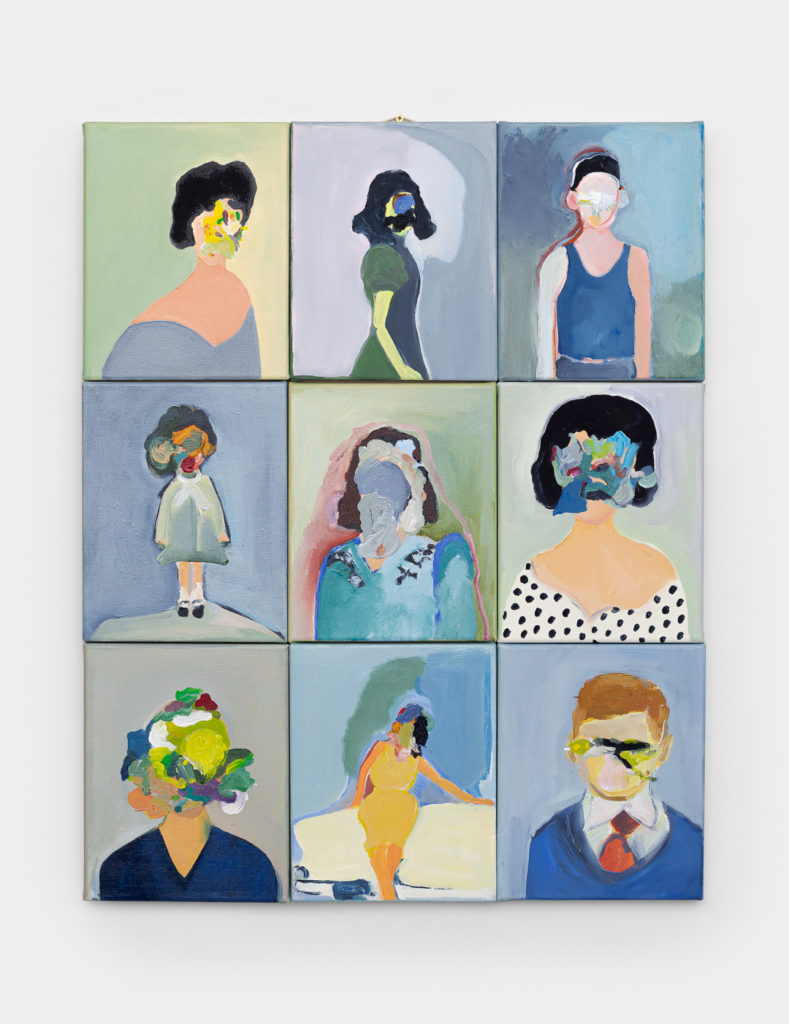

THERE ARE NO cleaning wipes in this series of family portraits, but the faces of everyone have been wiped out. A kind of thinking work is happening in that erasure. ‘I was thinking of faces,’ Brescia tells me. ‘Duplicity. What we are told and what the truth is. I’m staring at the faces of people I know. Of my family and I’m thinking about how you can’t read a face sometimes, so you don’t know what’s going on, therefore I’m abstracting it.’

These images were made after her daughter accused a family member of sexually assaulting her when she was a child. A number of artists have quite famously erased the faces of family members – as Vanessa Bell did to her sister Virginia Woolf – in order to show their subjects’ inner torment. I would argue that the erasure Brescia is engaged in is perhaps more a representation of the complexity and torment of the artist’s mind rather than the subject’s. It’s a reminder that domestic work isn’t just about cleaning wipes and sponges. It’s about the emotional load we carry as mothers and spouses. We carry the caring load, not just the cleaning load – and the weight of that is enormous, particularly in times of crisis.

I am interested in the art, and I am also interested in the artist. I’m interested in the art but I’m also interested in motherhood, in the domestic and suburban.

Linda Brescia, Parramatta Mission Series, 2013–15

HERE’S A SERIES I adore, made after the series of family portraits with the wiped-out faces. Brescia has made costumes of women’s bodies and she’s wearing them because it allows her the confidence to be a woman in public.

The Parramatta Mission Series makes me think of images I’ve seen of women standing tentatively on inner-city street corners, holding signs, at the start of the feminist movements of the late 1960s. And perhaps Brescia is imitating something from afar – she is, after all, from the outskirts of south-western Sydney. From a migrant working-class family. She’s from out there, from deep suburbia, where it doesn’t feel like art happens as much. ‘I remember what it was like for me then,’ she says when I ask her about these images. ‘My mum offered to pick up my children from school so that I could be at TAFE until four o’clock. It was such a big deal for me, just for me to take two days out. I remember I couldn’t even sleep the night before. That was a big turning point, when I gave myself those things.’

Brescia studied art later in life. She went back to TAFE as a mature-age student. An act of desperation, it was also something that made her feel insecure and unsure.

‘I had to be covered to have the confidence to go out in public. I remember being with groups of art people and just feeling like I had nothing to say because I’d gone from just being a mum, being at home. Then I started to mix with art people, I could relate to other women, other artists in some way but I felt completely alienated from the art world. Now it doesn’t worry me so much. Covering was very freeing for me.’

That’s why a lot of her earlier artwork looks like this:

Linda Brescia, Life and Death, 2012

IN THESE COSTUMES Brescia gets to be between absence and presence, the invisible and visible. The naked woman’s body is the purest form of womanhood and yet by wearing these costumes, Brescia reduces it to linear forms and flattened images. She’s an everywoman trying to work out how she wants to be visible. ‘I’ve got my life back. I’m coming out of it.’ There is a crack in her voice as she says this. You might not be able to hear it when you read the words I write on this page. ‘If I have to think of the biggest shift now, it’s having the confidence to show my face.’

I see those costumes as something that helped Brescia come out as herself – they are a transitional space where she can practise being seen, at least as an everywoman before she’s confident enough to reveal herself as the artist – a woman who is – more than the domestic suburban mother.

IN RECENT ARTWORKS – such as Dream Sequence 8 – Hands on Hildegard – Brescia literally takes on the body of other female artists. In video and performance art she becomes other women whose own lives had a performative quality: abbess and composer Hildegard of Bingen; dadaist poet and visual artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven; collector Peggy Guggenheim. ‘These videos are the first time I’ve spoken in my work and that was a hurdle I had to overcome. Part of me could kind of cringe about that but I feel like it’s the first time I’ve just been able to accept and feel comfortable with myself.’

Hands On Hildegard was composed for the UTP lockdown series Dream Sequence. What appealed to Linda about Hildegard was her interest in nature and plants. As a nun, Hildegard navigated a world where men were in charge. She was able to speak as a woman, to get around rules by saying that God had passed on a message to her. She managed to push her own agenda. Brescia says she’s ‘been interested in God and in who speaks to God for a long time’. She used to be very religious but gave up her faith around the same time her family fell apart in the aftermath of her daughter’s traumatic revelations.

In Hands on Hildegard domestic life literally splits open the artistic life. Images of Brescia in her flannel pyjamas, walking the dog and cooking, appear at the outer edges of the frame. All of this domesticity is interrupted by the image of her painting, making art. Throughout the video Brescia is dressed as a nun; she sounds like a mother in both the literal and religious sense. In the final sequence she sings the Lesley Gore song ‘You Don’t Own Me’. ‘Don’t tell me what to do and don’t tell me what to say,’ she croons into the camera.

I ask Brescia if these women are her alter egos, if she’s now trying to be something larger by stepping into the body of a woman who is more visible than herself. She replies, ‘We are lucky that we even know these women existed’. There is a dialogue between her and these women that she becomes. Brescia calls it ‘a blatant cry for recognition’. Looking at that work you can see that cry going from them to her and back again.

Linda Brescia Skirts, 2021, installation view, Wainwright Park, Kingswood, NSW. Produced and presented by C3West on behalf of the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in partnership with Penrith City Council. Photo: Jessica Maurer

WHEN I LOOK at Brescia’s work I can see that she’s engaged in a long, unending dialogue with women that she hasn’t necessarily met as well as with those she has. Brescia has been involved in community-based art practice since very early on, primarily within Sydney’s western suburbs, where she has worked with women, the elderly, people with disabilities and others to create collective and site-responsive works.

In her latest project, Brescia has been working with women in the Kingswood community, leading the Museum of Contemporary Art’s latest C3West project, Skirts, a visual arts response to the needs and desires of local women.

Beside a strip of chicken shops and pubs and charity shops hang sixteen banners onto which Brescia has painted the words and images of local women in Wainwright Park. These banners are the visual result of several months of workshops and consultations with women who live out here in deep suburbia, as Brescia does, on the outskirts of nearby Fairfield.

When I look at the banners I think of a rhetorical question Brescia proposed in an earlier conversation: she was considering how she could move from her more interior domestic life to the wider world of art. ‘That’s my world,’ she said, and then wondered, ‘How do I go from that to the bigger world? Where do I fit?’

The answer is here, in this artwork, in Wainwright Park. The women and their words painted onto fabrics are her posse and ours and their own and every woman’s. This is not just an artwork, it’s an occupation. They own the space. They are the space. To borrow from the title of one of Brescia’s earlier exhibits, these women are ‘holding up the sky’. In this work she’s taken all the women in this community and made them visible too. They’ve got nowhere to hide. No mask to wear. They’ve become a bunch of stories about women that rub up against each other in surprising and difficult and joyous ways, a part of a larger story about women and how we are seen and unseen in our places.

Photo taken by Felicity Castagna on her phone

THIS IS NOT a Linda Brescia artwork; these are my feet. I’m sitting on a couch in the studio we share together at the Parramatta Artists’ Studios in Rydalmere. I’m writing this essay and Brescia is painting me. We discuss whether we have made dinner this morning before coming in, or if we will leave early to make it. Children call. Fights break out. Negotiations. I pull an art book about feminist theory from the shelf and Brescia’s son calls wanting to know how to cook chicken wings. We are trying to escape but we’re both here trying to be away from home but also making art about homes, domestic spaces, the vast expanses of suburbia and the women within them. When Brescia reads my essay later she wonders if perhaps I’m projecting a lot of myself into it – if I’m not writing just as much about my own frustrations at being a Domestic. Suburban. Mother.

Perhaps I am.

I have this thought: there is a distinct absence of children in Brescia’s work – work I consider to be about motherhood – yet that image of a basket full of washing clearly says motherhood to me. The absence of children acts as a way of evoking, yet not fully conveying, the maternal. We know that mothering is there going on in the background and the significance is only highlighted by the absence of children. This is an act that I think speaks to what it means to be a mother: you always carry your kids with you even when they’re not there.

Share article

About the author

Felicity Castagna

Felicity Castagna is a lecturer in creative writing at the Writing and Society Research Centre, Western Sydney University. She has published four novels for...